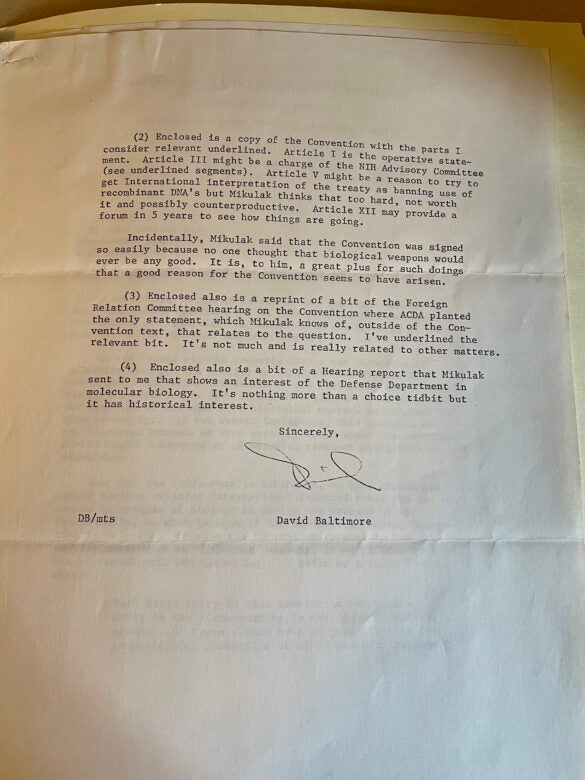

Baltimore’s letter also recounts a comment that Mikulak made that “the Convention was signed so easily because no one thought that biological weapons would ever be any good. It is, to him, a great plus for such doings that a good reason for the Convention seems to have arisen.”

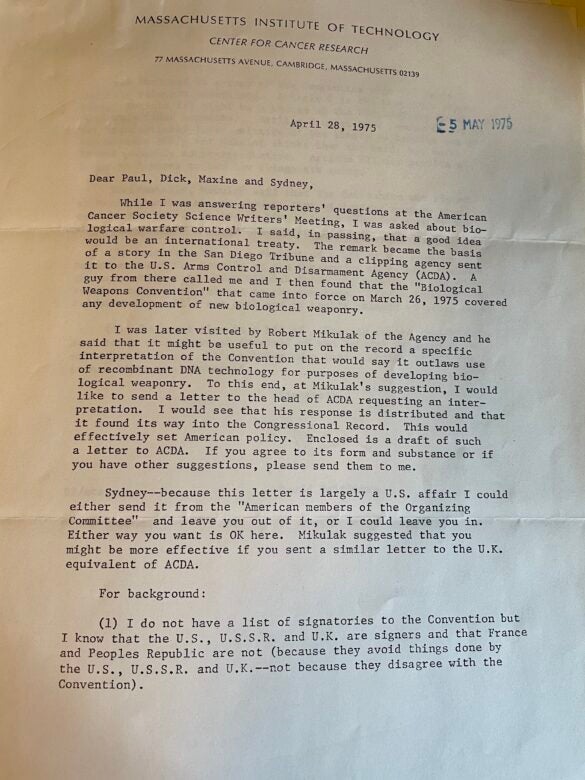

The Biological Weapons Convention was negotiated in the late 60s and very early 70s, just as rDNA technology was being developed. The treaty was finalized in 1972, so there had not been time for new developments in biology to have affected the participating countries’ policies on biological weapons. By 1975, most scientists were coming around to the idea that the use of rDNA techniques in basic biological and biomedical research was not dangerous, although a significant portion of the public and many politicians disagreed. It was, however, recognized by scientists and laypeople alike that the potential weaponization of this knowledge was a problem to be addressed. The fear that rDNA would be used to create bioweapons was a recurring theme in discussions of the new technology and its potential uses. The conversations recorded in the letter illustrate the extent to which rDNA research and its still-unknown applications was on scientists’ and politicians’ minds in the 1970s. One, it was a potential source of new and dangerous weapons, as Mikulak indicated when he said there ought to be an explicit understanding that these were covered by the treaty. In addition, it was a useful political tool to give more weight to a weapons convention that Mikulak believed necessary anyway, even if others in the political world had not.

This document is from the Sydney Brenner Collection, Series 4: Subject Files, Subseries 1: General, Box 3, Folder: Biological Warfare, 1975.