Exploring the Norton Zinder Collection: Being “Scooped”, Then and Now

By Antoinette Sutto, Robert D. L. Gardiner Historian, sutto@cshl.edu

This is the first of a series of essays exploring important documents and themes within the Norton Zinder Collection.

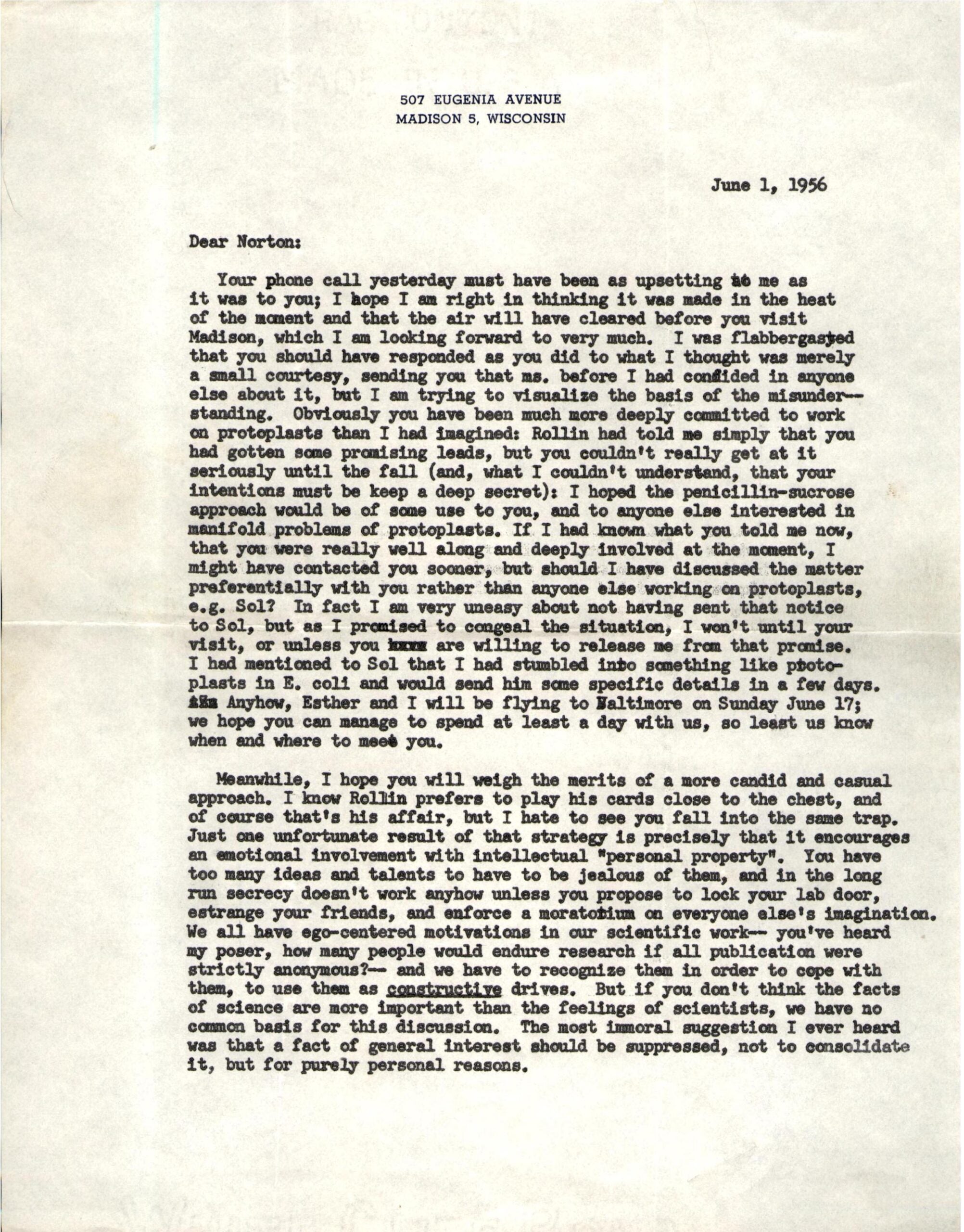

Early in the summer of 1956, Norton Zinder and Joshua Lederberg had a heated telephone conversation about a forthcoming paper of Lederberg’s in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.1 Zinder and Lederberg had known each other for years. Zinder had worked with Lederberg as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin and they had published several papers together, including their famous work on transduction in salmonella bacteria.2 The two were friends as well as colleagues, which meant that the conflict was personal as well as professional. The day after the phone conversation, Lederberg wrote to Zinder to try to work the issue out, and Zinder replied to the letter a few days later.3

What was the problem? Lederberg had scooped Zinder — sort of. Both Lederberg and Zinder had been working on creating E. coli protoplasts. Protoplasts are cells that have had their cell walls stripped away, and are used for a variety of research purposes in biology. In the spring of 1956, Lederberg sent Zinder a manuscript that described a new way to create E. coli protoplasts using penicillin. Lederberg hadn’t known that Zinder had been doing some very closely related work in collaboration with his Rockefeller colleague Rollin Hotchkiss — or at least hadn’t known that this was a project that Zinder had already made substantial progress on. Lederberg had in fact talked to Hotchkiss, who told him that Zinder wouldn’t really be able to get into the protoplast work until the fall. Lederberg told Zinder about a conversation he had had with Hotchkiss about this research topic and some reading he had done, after which he had the idea to use penicillin, sucrose and magnesium ions to create protoplasts from enteric bacteria like E. coli or salmonella. He tried it out, it worked, and he decided to get the paper about the method out there, even though, as he said to Zinder, he didn’t think it was a stellar paper in and of itself; his goal was simply to share the method.

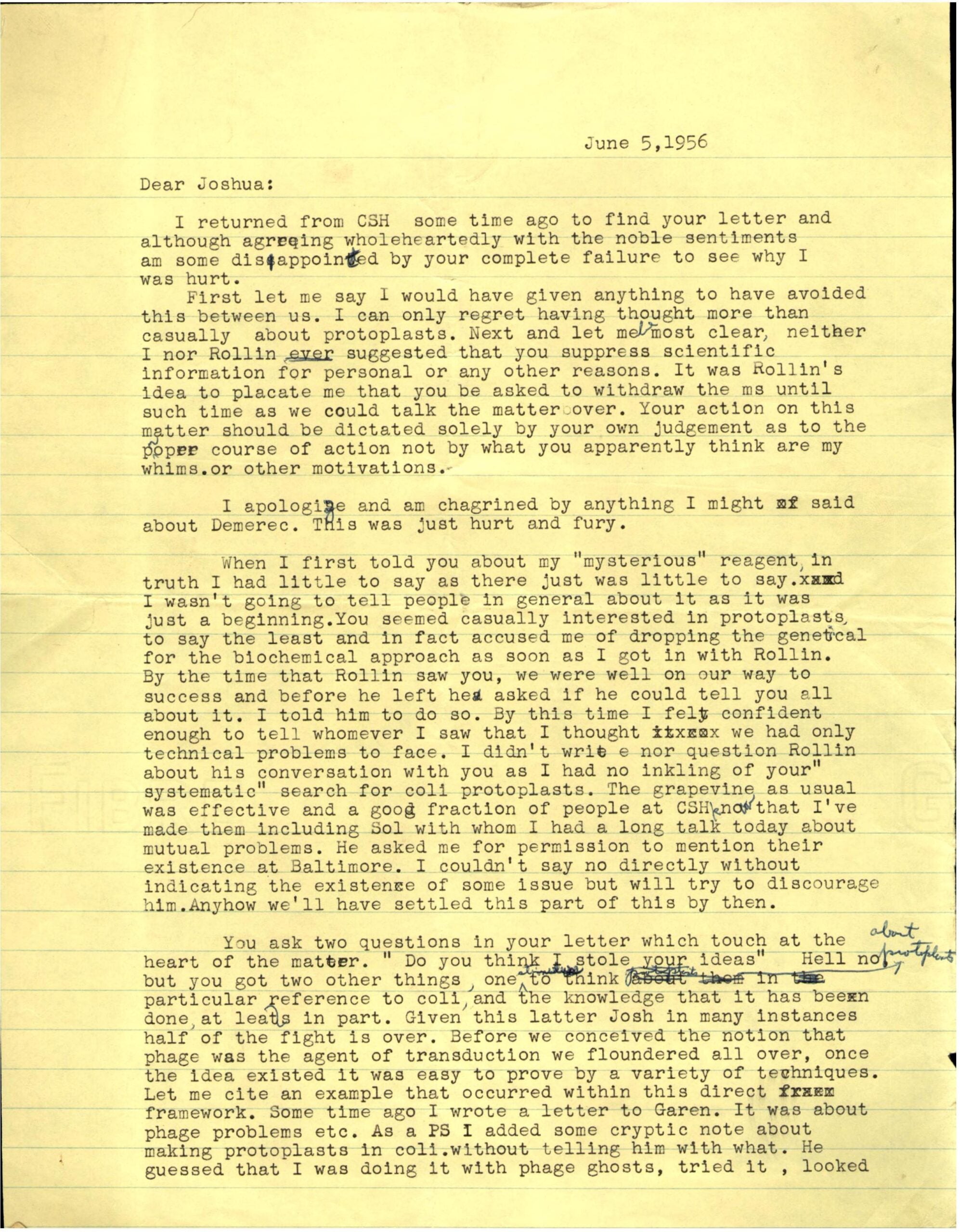

Zinder, who had come up independently with the same method for creating protoplasts, remembered an earlier conversation with Lederberg about it, in which he hadn’t said much about the progress he had made because it was still quite early in the process, and his impression had been that Lederberg’s interest in protoplasts was only casual. By the time that Lederberg talked to Hotchkiss, however, Zinder and Hotchkiss had made considerable progress. Hotchkiss had asked Zinder if he could talk to Lederberg about the project, and Zinder had said yes, since in his view the work was fairly far along. Because Zinder hadn’t known that Lederberg was interested in protoplasts, he didn’t ask Hotchkiss about his conversation with Lederberg and so hadn’t known about Lederberg’s project until the latter sent him the manuscript.

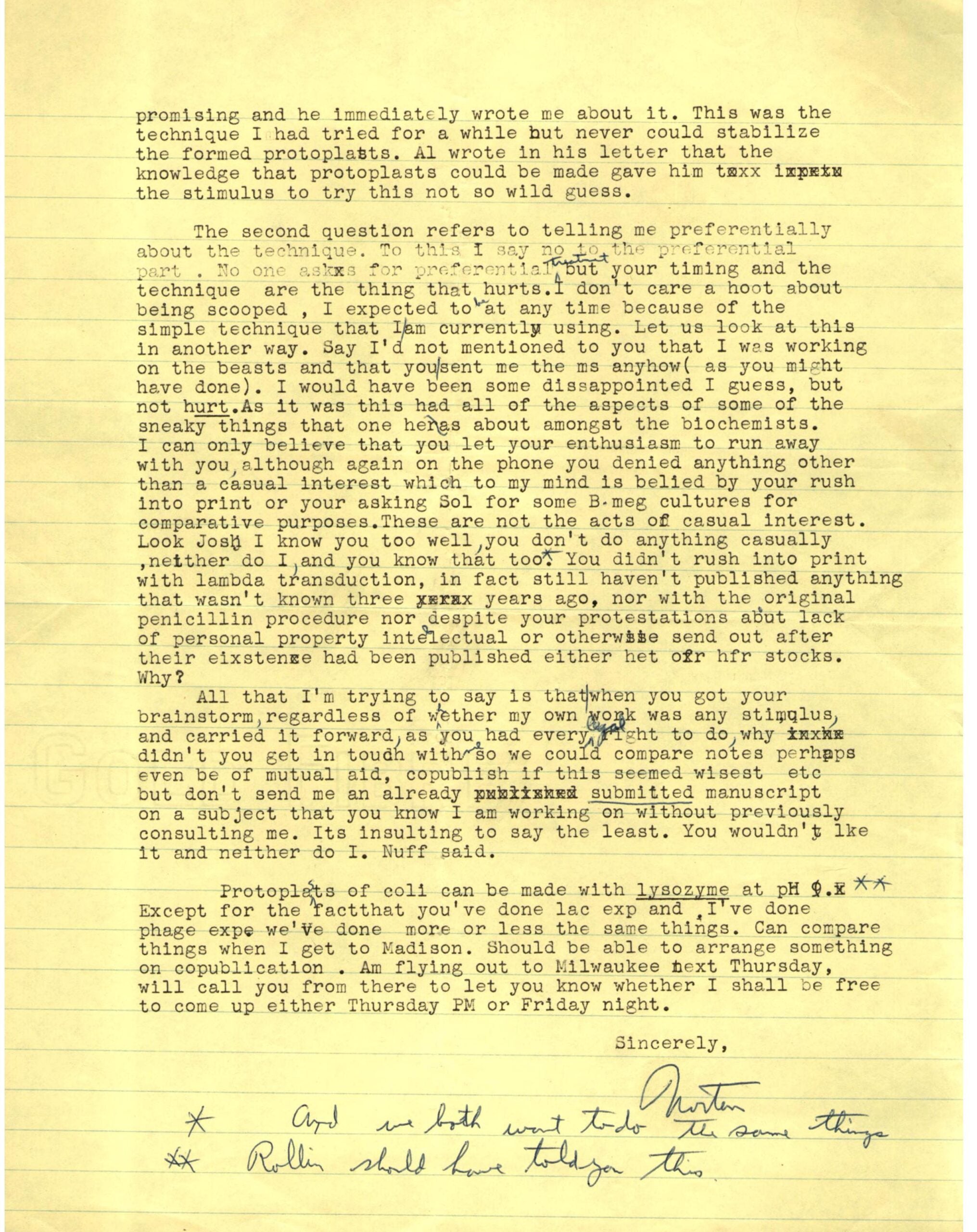

The problem might seem to be Lederberg’s apparent scoop of Zinder — or his publication, without crediting Zinder, of a method that Zinder might reasonably claim Lederberg had gotten at least partially from his conversation with Hotchkiss about Hotchkiss and Zinder’s work. In his letter, Lederberg asked Zinder point blank, “Did you think I stole some of your ideas?” But Zinder didn’t think this. As he put it in his reply, directly addressing Lederberg’s question about theft: “Hell no!” Instead, the issue was a little more complex. From his point of view, it seemed that while Lederberg hadn’t stolen his ideas, he had gotten “two other things, one stimulus to think about protoplasts in particular reference to coli, and [two] the knowledge that it has been done, at least in part. Given this latter Josh in many instances half of the fight is over.” And given that Lederberg had received this stimulus and knowledge from Zinder, Zinder was hurt and insulted that Lederberg hadn’t talked with him about it and had instead just sent him the manuscript:

All that I’m trying to say is that when you got your brainstorm, regardless of whether my own work was any stimulus, and carried it forward, as you had every [‘legal’ inserted] right to do, why didn’t you get in touch with me so we could compare notes perhaps even be of mutual aid, co-publish if this seemed wisest etc. but don’t send me an already submitted manuscript on a subject you know I am working on without previously consulting me. It’s insulting to say the least. You wouldn’t like it and neither do I. Nuff said.

Lederberg saw the situation differently, and it led him into some larger questions about scientific etiquette and professional obligation. First, he didn’t like the idea of “suppressing” material out of obligation to someone else who was working on a similar project (Zinder disagreed vociferously with this characterization of the situation — he insisted that he had ever asked Lederberg to do any such thing). Related to this was the question of whether anyone ever owed anyone else “preferential” discussion of research results. Did a longstanding friendship or working relationship create this kind of obligation? What about simple collegiality — did knowing that a specific other researcher was working on a similar project create an obligation, or if ‘obligation’ was too strong a word, a sense that it would be the right thing to do to talk to that person? Lederberg said that if he had known that Zinder’s work was so far along, “I might have contacted you sooner, but should I have discussed the matter preferentially with you rather than anyone else working on protoplasts, e.g. Sol [Spiegelman]?” Lederberg confessed that he in fact felt “uneasy” about not having talked with Spiegelman about what he was doing.

More than that, Lederberg wondered, was what either of them was doing completely original? He wondered if they both weren’t “aping Sol more than a little…I know I was tremendously stimulated by his account at Detroit, probably I would never have systematically looked for E. coli protoplasts” if not for that. Given that communication among scientists and the sharing of ideas was a key part of how knowledge was built, questions of influence, credit and originality could become very complex. What was “stimulus” or information that should be credited or acknowledged through a conversation or letter before the publication of a paper, and what was simply the normal sparking of ideas through contact with other scientists?

Lederberg was moved to expound a little further on the role of the ego in science. He noted that some scientists, such as Rollin Hotchkiss, were prone to “play [their] cards close to the chest,” and not talk about what they were working on. Lederberg hoped that Zinder would “weigh the merits of a more candid and casual approach” and “not fall into the same trap,” because such a strategy of secrecy “encourages an emotional involvement with intellectual ‘personal property.’” Being “jealous” of one’s own ideas was a bad way to go about things, and in addition to that, it was ineffective: “in the long run secrecy doesn’t work anyhow unless you propose to lock your lab door, estrange your friends, and enforce a moratorium on everyone else’s imagination.” In his view, Zinder’s reaction to his protoplast paper showed the danger of investing too much of oneself and one’s emotions in the work. “Ego-centered motivations” were always going to be there “and we have to recognize them in order to cope with them,” but ultimately, he hoped that Zinder would recognize that “the facts of science are more important than the feelings of scientists.”

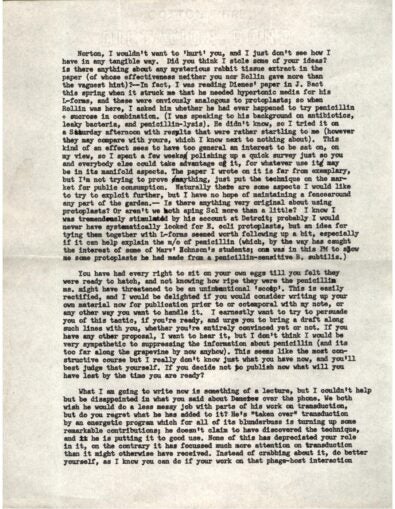

How realistic was Lederberg’s expectation that scientists could trust in their own continued creativity and thus not get too attached to any one particular piece of work? He was trying to convince Zinder that he, Zinder, was too talented and productive to worry about insisting on ownership of any one particular method or discovery. This was a flattering idea, and it was perhaps an idealistic conception of scientists to suggest that they could and should strive to put ego and normal human emotions aside in the interest of the pursuit of scientific discovery. Competition and the fear of being scooped were a real part of the day to day process of doing science — if it was a bad idea to try to guard one’s work and play one’s cards close to the chest like Hotchkiss, how should scientists deal with these challenges?

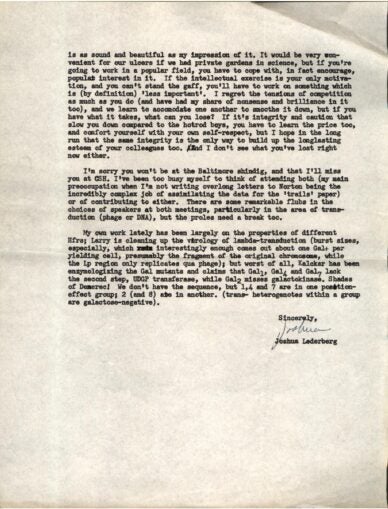

Lederberg’s take was of the ‘if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen’ variety. He noted that “it would be very convenient for our ulcers if we had private gardens in science, but if you’re going to work in a popular field, you have to cope with, in fact encourage” other researchers’ interest in it, and if that was not acceptable, “you’ll have to work on something which is… ‘less important.’” He didn’t think that competition was a positive thing in and of itself, but rather a part of the process that had to be dealt with and managed. Scientists had to “learn to accommodate one another to smooth…down” the “tensions of competition.” In the end, though, what did Zinder really have to fear? He was a talented scientist with the chops to succeed.

Finally, Lederberg referred to a perennial issue in science, the tension between, on the one hand, wanting to carry out a project thoroughly and methodically in order to ensure the integrity of the results and, on the other, the need to get the results out quick to secure priority. As he saw it, sometimes losing out in the short term was the price to be paid for doing things right. “If it’s integrity and caution that slow you down compared to the hotrod boys, you have to learn the price too, and comfort yourself with your own self-respect.” Besides, he thought, the high road was a better strategy in the long run anyway.

This exchange of letters between two young molecular biologists in the 1950s highlights a series of important questions about competition, collegiality and priority that are still the focus of discussion and debate today. Being scooped is something that researchers continue to worry about, just like the need to balance the desire to do thorough work with the fear of being too slow. How open should you be about your data and methods? How much assistance should you offer colleagues working on similar projects? How much can other scientists be trusted to collaborate with rather than scoop you? Are there norms of scientific etiquette that everyone can be expected to follow, or is this just wishful thinking? These questions are no easier to answer today than they were in the 1950s. In molecular biology, the situation has been further complicated by the field’s connection to commercial biotechnology, which has created pressure to stake out claims on specific discoveries as soon and as definitively as possible in order to patent and commercialize them. In addition, changes in the scale on which data is generated and how it is shared have created new flavors of scoop: in 2002, one researcher whose team had generated a large amount of genetic data and made it available online discovered that a colleague had taken the data and used it to publish a paper. The data’s creator called this an “egregious” violation of scientific etiquette, and the incident led others in the field to offer opinions on what the expectations actually were in this type of situation — it was far from clear what, if anything, to do about this kind of behavior.4

But it’s worth stopping to ask a few questions about being “scooped.” How often does it happen, and is it really the death-knell for a project, as is often assumed? How does the fear of being scooped affect the quality of research? There is reason to believe that competition and the drive to publish first at all costs has a negative effect on the quality of what is published. One study carried out by metascience researchers modeled the behavior of scientists using bots. They varied the size of the reward for publishing first and found that when the bots were offered large rewards for publishing first, they tended to push through the research quickly and gathered less data, but when the reward for being first was smaller, these bot “scientists” collected larger data sets and published at a more leisurely pace.5 At the same time, there is also evidence to suggest that the penalty for being scooped is not as drastic as a lot of scientists assume. A study carried out by two economists using data from the Protein Data Bank (a database of structures of proteins and other biomolecules) showed that while being first does make a difference in terms of the prestige of the journal in which results are published and the number of citations, the difference is not as significant as people believe.6

Nevertheless, the fear of being scooped and the potential detrimental effects — papers that don’t get published, rejected grant applications, abandoned projects, lost time and money — are not to be discounted. Fortunately, as the bot study suggests, scientific culture is malleable and norms and expectations can be changed.

Several journals have recently taken steps to address the problem of scooping. In January of 2018, PLOS Biology published a statement about a change in their editorial policy which would allow for the publication of “complementary research.” To be considered complementary research, a paper has to cover essentially the same research on the same system as a previous paper and come to a similar conclusion; the second paper must be submitted within six months of the publication date of the first. The reasoning behind this has to do with “the current concern regarding the reproducibility, or lack thereof, of scientific findings.” Complementary research allows for an “organic” reproduction of the results and thus increases confidence in them.7

Six months after the announcement of this new policy, PLOS Biology published the first-person accounts of two investigators, a “scooper” and a “scoopee” to show how the publication of “complementary research” worked in practice. These two investigators brought up many of the issues the editors of the journal had touched on in their editorial — the value of scooped studies as confirmation of the studies that were published first, and that no one wants to see months or years of effort relegated to the recycling bin. The investigator who was scooped, Jacob Corn, pointed out that scientists and journals have in effect created the problem of scooping for themselves, arguing that “the incredible pain of being scooped is an artificial construct.” A “focus on novelty above reproducibility” had created a situation in which “what might once have been the sting of being published second has mutated into the deep wound of not being published at all.” PLOS’s new policy was designed to both mitigate this pain and address the reproducibility issue. Jin-Soo Kim, the scooper in this case, described being scooped himself in the past, stressing that he felt “lucky to have survived many such cases but will never forget those moments, which still hurt.” In this instance, where he and his team were the first to publish, Kim emphasized the collegiality of Corn’s team and said that given the discussion of his team’s work in Corn’s paper, he expected that their paper would receive renewed attention when that of Corn’s team appeared.8

The claim that the publication of complementary papers is good for the scientific community as a whole was also made by the editor of Cell Systems in November of 2018 when the journal announced its own policy of publishing “scooped” papers. The editorial pointed out that the term “scoop” itself was not ideal, since “it draws a false equivalence between publishing scientific work and reporting the news.” The core of the editorial, however was about how scooping is bad for the scientific community as a whole, since the publication of two papers covering similar experiments is actually very helpful for other researchers working on similar problems — two different papers would likely offer slightly different methods or experimental designs for comparison, which would help determine the best research strategy going forward.9 The publication of complementary research is not a consolation prize for the team that came second. Rather, it’s a way of helping to move the field forward as a whole. Had Zinder published his protoplast research at the same time or just after Lederberg published his, the two papers might have complemented each other in precisely this way.

The conversation about “scooping” in recent years and the efforts to change the culture of scientific publication show both what has changed since Zinder and Lederberg’s discussion in the 1950s and what has stayed the same. What hasn’t changed are the strong identification of the researcher with the research and the intensely personal reactions to scoops, or apparent scoops. Zinder was clear that he was personally hurt that Lederberg didn’t talk to him before publishing his protoplast manuscript; Jacob Corn and Jin-Soo Kim both mention the intense sting, the emotional wallop of being scooped, even when the scoop is unintentional, which they mostly are.

Lederberg lectured Zinder on the importance of letting go of ego-centered motivations and recognizing that you can’t have a particular subfield in science all to yourself. Easier said than done, one might respond, especially given the drastic professional consequences that many scientists fear in connection with being scooped. Lederberg’s point of view rested on the assumption that the competition was always going to be there — even if scientists made efforts to manage it, it was a given of the profession.

This is in contrast to the recent changes in some journals’ editorial policy, which rest on the assumption that the profession doesn’t necessarily have to continue operating the way it has operated in the past, that the norms can be tweaked in such a way that everyone benefits from the change. Would such a change in journal policy have been an option in the late 1950s? Or is it that scientists have grown more reflective about science as a project in the intervening decades, and more willing to articulate and question the norms of their profession?

Either way, the changes in publication policy that some journals have made seem to move towards what Lederberg implied back in 1956, that it’s better to think in terms of what is good for the progress of knowledge rather than what is good for you personally. This is true even though the context is different — Lederberg had been talking about not getting too attached to your research because you might get scooped, while PLOS Biology and Cell Systems are talking about changing the all or nothing aspect of scientific publication, that is, getting rid of the “scoop” in the first place.

1 Joshua Lederberg, “Bacterial Protoplasts Induced by Penicillin,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 42, 9 (Sept. 1956): 574-577.

2 Zinder, Norton and Joshua Lederberg, “Genetic exchange in salmonella,” Journal of Bacteriology 64, 5 (1952): 679-699.

3 Joshua Lederberg to Norton Zinder, June 1, 1956 and Norton Zinder to Joshua Lederberg, June 5, 1956, Norton Zinder Collection, Series: Rockefeller University, Box 7, Folder: Miscellaneous Correspondence, 1952-1958, CSHL Archives.

4 Eliot Marshall, “DNA Sequencer Protests Being Scooped With His Own Data,” Science 295, no. 5558 (Feb. 15, 2002): 1206-1207.

5 Cathleen O’Grady, “Risk of being scooped drives scientists to shoddy methods,” Science [AAAS Magazine] January 28, 2021, via www.sciencemag.org. Accessed 7/8/21.

6 Ewen Calloway, “Scooped in Science: Relax, Credit Will Come Your Way,” Nature 575 (28 November 2019): 576-577.

7 PLOS Biology Editors, “The importance of being second,” PLOS Biology 16, 1 (Jan. 29, 2018).

8 Jin-Soo Kim and Jacob Corn, “Sometimes you’re the scooper, and sometimes you get scooped: how to turn both into something good,” PLOS Biology 16, 7 (July 16, 2018).

9 Quincey Justman, editor, Cell Systems, “ ‘Scooping’ hurts science and scientists,” Cell Systems 7 (November 28, 2018): 469-470.

[aria-label=”Ask Us”] { display: none; }