The Biological Laboratory and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences

By Antoinette Sutto, Robert D. L. Gardiner Historian, sutto@cshl.edu

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was originally two separate institutions, the Department of Genetics, which was a part of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and the Biological Laboratory, which was run first by the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and later by the Long Island Biological Association. The two were fused into a single institution later in the twentieth century.

The Biological Laboratory’s early connection with the Brooklyn Institute is an important part of Cold Spring Harbor’s history. A close look at the lab’s first decades not only reveals an institution very different from the laboratory in its current form but also sheds light on the history of the discipline of biology in the United States.

What was the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences? What was it like to study biology at Cold Spring Harbor between 1890 and 1920? To answer these questions, the best place to start is the second decade of the twentieth century, when scientists, patrons and educators were engaged in an intense discussion over what, precisely, the Biological Laboratory’s mission was and how that mission ought to be carried out.

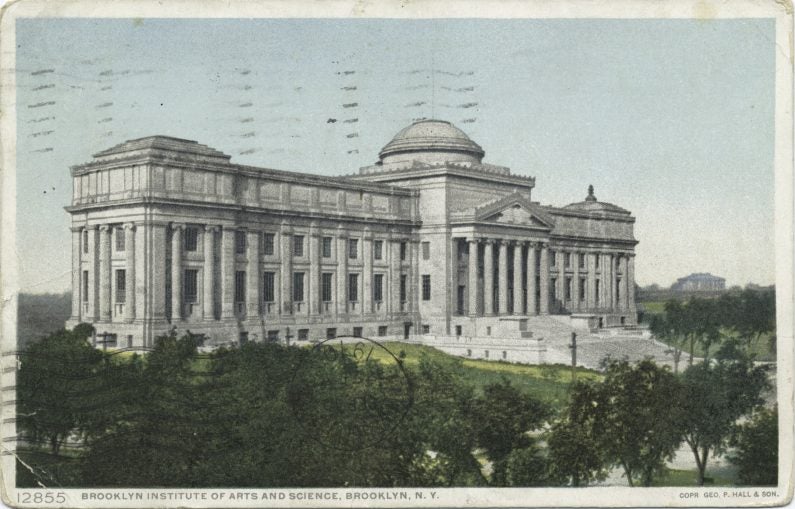

An observer in 1915 or 1920 familiar with both the Biological Laboratory and the Brooklyn Institute for Arts and Sciences would have said that the relationship between the two was unusual. The Biological Laboratory was part of the Brooklyn Institute, but unlike the Brooklyn Institute’s other establishments, such as the Brooklyn Museum or the Botanic Garden, the Biological Laboratory was not in New York City. In terms of administration, it was not managed as directly by the Brooklyn Institute as were the Institute’s other educational and cultural projects. In the mid-1910s, as the Brooklyn Institute was revising its constitution, those involved in the process repeatedly raised questions about the Biological Laboratory — how should it be included in the Brooklyn Institute’s new constitution, if at all?

There was significant internal conflict over this issue. The newly reconstituted Brooklyn Institute was to be made up of a series of departments, one for each of its sub-institutions (the Botanic Garden, the Museum, and so on). Should the Biological Laboratory be a department? What precisely was its status within the organization? C. Stuart Gager, director of the Botanic Garden, wrote to Charles Davenport in January of 1915 to describe the ongoing institutional reorganization of the Brooklyn Institute and told him that he had spoken to one of the Brooklyn Institute trustees about the Biological Laboratory. This trustee, according to Gager, considered the lab a separate institution, for which the Brooklyn Institute merely administered some funds (Gager didn’t name the fund in the letter, but it was the Temple Prime Scholarship Fund). Gager’s understanding was that Franklin W. Hooper, the former director of the Brooklyn Institute who had been instrumental in founding the Biological Laboratory in 1890, had always considered it a key part of the Brooklyn Institute. Gager wanted to know what Davenport thought about all this.1

Davenport’s view was that the lab certainly ought to be a department of the Brooklyn Institute.2 Not everyone else agreed, however. The loose institutional relationship between the Biological Laboratory and the Institute gave a number of people pause. Walter Crittenden of the Brooklyn Museum told Gager that he thought the lab’s connection to the Institute was “a very loose one.” Either the Biological Laboratory should be managed like the other departments, or the institutional link between it and the Brooklyn Institute should be severed. He added that he didn’t think that it would be a good idea for the Brooklyn Institute to take on the responsibility of a more active management of the lab.3 It was essentially an argument for cutting the Biological Laboratory loose. Robert S. Woodward, president of the Carnegie Institution, pointed out that the Biological Laboratory had not been mentioned in Brooklyn Institute’s previous constitution, and that the loose institutional connection had been intentional. Franklin Hooper and the lab’s other key patron, Eugene Blackford, had arranged for an “independent organization” for the Laboratory, with “your own officers and trustees, few of whom are trustees or members of the Brooklyn Institute.”4

In the end, Davenport succeeded in having the Biological Laboratory included as a Department of the Brooklyn Institute and was named its director. But this victory left unanswered the question of whether the Biological Laboratory really was, or ought to be, part of the Brooklyn Institute.

Seen from the perspective of the late 1910s and 1920s, it might seem that the Biological Laboratory had been a kind of eccentric side project from the Brooklyn Institute’s point of view. Certainly, the fact that the Institute and the Laboratory parted ways in the 1920s suggests that the relationship was not set up to succeed in the long term. More generally, the historical writing on Cold Spring Harbor tends to look backward from the point of view of what the laboratory eventually became: an institution focused primarily on professional research. Seen from this angle, the Brooklyn Institute period is understood mainly as a prelude to the laboratory becoming “more advanced and professional” and entering into its real history as a “serious scientific research and teaching institution.”5

This point of view downplays the relevance of the Brooklyn Institute for the history of Cold Spring Harbor. The lab’s first decades should not be discounted, however. A closer look at the Biological Laboratory between 1890 and 1915 offers a glimpse into a pivotal moment in the history of the life sciences in the United States. The scientific and pedagogical activity that took place there, as well as the institutional and professional ties between the Biological Laboratory, the Brooklyn Institute, and other institutions and individuals, were part of a series of important shifts in the history of biology and the history of science pedagogy. The Biological Laboratory’s first decades were not a simple precursor to what came later; rather, they are significant in and of themselves. Moreover, through the DNA Learning Center, Cold Spring Harbor both maintains an important connection to the city of Brooklyn and furthers the Brooklyn Institute’s longstanding mission of promoting public engagement with science.

What sort of organization was the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences? It had been founded in 1823 as a library for apprentices — an organization, other words, dedicated to giving people without extensive formal schooling access to education. By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, however, the organization had fallen into a state of atrophy. In the late 1880s, the Brooklyn Institute underwent a significant reorganization — one contemporary observer went so far as to call it a “new lease of life.” What had been a “fossil society” became “an educational power which is recognized all over the country.”6 The Brooklyn Institute’s mission was and remained the education of the general public, but this mission was now being undertaken on a much grander scale. The Institute created a series of scientific “departments” dedicated to various branches of knowledge. Individuals could become members of whichever ones they liked with the payment of a single membership fee; there were also numerous public lectures on scientific topics.7 Although professional scientists were among the members, the target audience for membership was “people of general culture, and…young men and women who, without being able to continue their studies in college, are intelligent and thoughtful and interested in one or more departments of study.”8 Soon after this, the Institute created the Brooklyn Museum, also dedicated to the edification of the general public, and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which was intended to be both a center of research and an institution dedicated to providing “instruction to both elementary and advanced classes in botany…cooperat[ing] in every feasible manner with the botanical work of the public and private schools of the Borough of Brooklyn.”9

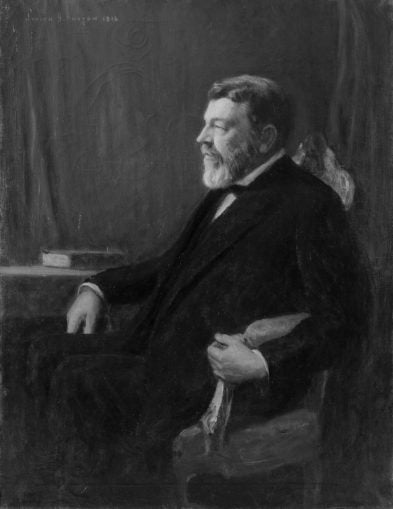

Contemporary observers gave Franklin W. Hooper (1851-1914) the credit for this transformation of the Brooklyn Institute. Hooper, who was both a scientist and an educator, headed the Brooklyn Institute beginning in 1889. He had studied the life sciences as an undergraduate at Harvard and later worked for the Smithsonian studying algae and corals along the Florida coast. For several years, he was a high school principal in New Hampshire, after which he taught chemistry and geology at Adelphi Academy in Brooklyn. Hooper had experience in biological research: in addition to his work for the Smithsonian, he had studied at the short-lived marine biology school run by Louis Agassiz on Penikese Island, off the coast of Massachusetts, in the 1870s.10 In other words, he had direct experience with the latest developments in the life sciences — in particular with marine biology.

Biology as an academic discipline was still in the process of formation in the late 1800s. The word “biology” itself dated back to the earlier part of the century, but until the late 1800s the study of the life sciences remained divided into the separate fields of botany, zoology, morphology, medicine, and so on. That there ought to be a single core discipline that would address fundamental questions relevant to all life-science fields was new idea in the late 1800s. Biology as it emerged in universities and research stations in the late 1800s and early 1900s involved

emphasis on certain basic concepts such as protoplasm, the cell, and evolution; ranking of research problems in order of importance and feasibility — with the embryology, cytology and physiology of invertebrates at the forefront; development and spread of a set of instruments and techniques, centered around the microscope; creation of institutions such as journals, graduate departments, and marine laboratories; development of college courses in “general biology” and promotion of a rationale for such elementary work…[and] mobilization of constituencies to provide financial and political support.11

Marine biology and the study of invertebrates were key to the new discipline. The academic institutions central to the development of biology in the late 1800s were primarily urban, which meant that biologists were confronted with a “limited…range of material — largely insects and domestic animals — available for laboratory work.” In the heat of summer, “work with organisms” was “disagreeable and sometimes dangerous.” The seashore was appealing because “organisms were abundant, fresh and either cheap or free for the taking…marine invertebrates were both more durable and less personable than higher animals, they were easier to manipulate while alive; they were, figuratively and sometimes literally, transparent to the sufficiently careful observer. They possessed unusual anatomic and physiological qualities and could provide valuable insights into the evolutionary crucial early stages of embryological development.”12 Marine laboratories, in other words, offered biologists an opportunity to address problems key to their discipline in a way that was cost-effective and efficient — and gave them a good research-related rationale to leave the city during the summer. Besides, middle- and upper-class Americans were already familiar with the idea of “summering,” i.e. getting out of the city to spend July and August in watering holes on the coast or in the countryside. The idea that academics might leave for cooler pastures in the summer was not surprising, and the transportation infrastructure to do so already existed in many areas.

Nevertheless, marine laboratories as they developed on the American coast in the late 1800s were not simply a necessary consequence of the requirements of the discipline or the summer migratory habits of well-to-do professors. Without the creativity and vision of biologist Charles O. Whitman, for example, the famous biological laboratory at Woods Hole (sometimes spelled “Woods Holl”) would not have come into being. Whitman valued informality and collegiality — years earlier, he had left a post in Japan when his superiors forbade him from treating his students like colleagues. He saw in Woods Hole an opportunity to offer investigators “rest and investigation.” The unstructured setting encouraged informality, flexibility and exchange about a wide variety of life-science problems. In other, more well-established scientific disciplines such as chemistry or psychology, the existing academic and professional structures encouraged practitioners, especially younger investigators, to narrow and specialize their work in order to stand out. Biology as it was done at Woods Hole, in contrast, allowed for the formation of a community of investigators interested in a broadly defined set of overlapping problems. The sub-disciplinary boundaries were not hard and fast, and researchers could range freely as they formulated and investigated scientific problems. In other words, the marine setting of a place like Woods Hole was congenial to the nuts and bolts of the discipline as it then existed (free invertebrates!) but more than this, the informal seaside setting facilitated a particular type of investigatory culture which proved to be very influential.13

Biology, then, took institutional and intellectual form in universities and at summer research stations at the turn of the twentieth century. The study of biology, however, as well as discussion of its disciplinary boundaries and practical applications, were not limited to these places. College students preparing for a career in education learned from professors who spent time in places like Woods Hole, and occasionally took courses there themselves. These individuals asked how biology could be taught to younger students. Just as biology was new at the college level, it was new at the high school level — “high school biology” as we know it was created very early in the twentieth century. It was added to the curriculum in Chicago public schools in the 1890s, for example, and in New York City in 1902.14

This new subject of high school biology is worth addressing in some detail, since the existence of high school biology would have important consequences for the Biological Laboratory as a teaching institution in the 1890s. What had high school students in New York City and elsewhere in America been learning about the living world previous to this change? Throughout most of the nineteenth century, relatively few students attended high school, and those who did typically went on to college. As a result, high school life-science education in the nineteenth century was structured around the academic subjects that students would study in college, which in turn reflected the structure of the life sciences as mid-nineteenth century academic researchers understood them: zoology, botany, and physiology. By the 1890s, “biology” as a research discipline encompassing all of the life sciences — the study of living things in general — was emerging at the university level, as we have seen.15 These changes at the university level naturally affected how the life sciences were taught to secondary school students.

Also in play at this juncture was an important transformation in the American education system which happened from roughly 1890 through 1920: the expansion of the American high school. It was in this period that secondary education became a mass phenomenon. Ideally, everyone was now supposed to attend high school, not just those who intended to go on to college. For educators, this change raised the question of how to teach the life sciences to young people who didn’t intend to go to college — and what the purpose of this education would be. This was the genesis of “high school biology” as a subject. The academic subject of biology was new in the 1890s and early 1900s, and the number of young people studying it was unprecedented.

Science is never done — or taught — in a vacuum. The men and women who designed high school biology courses and wrote general biology textbooks had particular goals and outcomes in mind that went beyond the communication of information about living things. High school biology was closely connected to progressive educational thinking. The new discipline focused on development, which “linked together embryology, natural and human history, psychology and philosophy.”16 The study of living things, in other words, was connected to grand philosophical themes related to development, evolution and progress. Educators believed that this would aid the students as human beings, helping them to see themselves in a larger context and providing them guidance not on just how life worked, but how to live. The lessons that students were to learn were not always positive, from our point of view. In the early twentieth century, scientists’ model of evolution still involved the idea of progress, which bled into ideas about the progress of species, “races” and societies that today are no longer scientifically tenable. These ideas were reflected in the textbooks of the day.17 On the whole, however, the goal of biology as these educators understood it was to help young people see themselves and their lives as part of the natural world. Emphasis was placed on the mutual interdependence of all life forms and the need for “respect and sympathy for life of other kinds.” Biology would also offer a gateway to discussion of the scientific principles behind good health and hygiene, the reasons behind public health measures and safety standards for food and medicine, and the dangers of “alcohol and narcotics.”18 Biology textbooks for high schoolers, such as that authored by former Biological Laboratory director H. W. Conn, explicitly linked “the latest scientific information in biology” to “habits of right living.”19

The genesis of high school biology overlapped with the development of a new method for teaching younger children about the natural world: nature study. Progressive reformers were concerned that American children, especially in urban areas, were losing touch with the natural world. They were also committed to a more practical, engaging, hands-on form of teaching than had been typical in schools in previous decades. Nature study as it emerged in the 1890s emphasized learning about the natural world through observation, experience and activity. Professional scientists were key figures in developing both the theory and the practice of nature study in schools.20 Nature study as a term was very broad, and not all the educators who claimed to be engaged in it would have agreed on how to do it or what its ultimate purpose was. Nature study could be taught with the goal of awakening children’s curiosity and powers of observation as a way of preparing them for a more in-depth study of science in high school; it could also be seen as a remedy for urban children’s lack of experience with and thus appreciation for nature — a kind of remedial course that would provide them with what their rural counterparts simply absorbed from their environment.21 In some cases, learning practical skills such as gardening were part of the goal as well. In general, with both nature study and high school biology, the point of teaching the life sciences was not necessarily to prepare students for college study or an eventual career in the sciences. Rather, it was about molding creative, engaged, thoughtful and responsible young citizens (and rectifying the damage that was assumed to be done by the modern, urbanized world).

Franklin Hooper was very familiar with these new currents in progressive science education. From a rural background himself, he was very much of the opinion that nature study would be good for urban children. Hooper expressed his views on education in a paper he read at the annual meeting of the American Association of Museums in June, 1913, in which he argued that the increasing industrialization of the United States had created an educational problem, because the most “natural and rational” education for young people was that which took place “on the farm[,] in a good home with a school which simply supplements the education of the farm and of the home, and makes of the farm life and home life a laboratory and workshop connected with the school.” Under these circumstances, he said, a young person who grew up on a farm might well understand botany better than a university-trained professional botanist.22 Hooper applied these views to his work at the Brooklyn Institute. In a letter to Charles Davenport in 1902, for example, Hooper described the search for a curator of the Institute’s Children’s Museum. They were seeking someone with “broad knowledge in the Natural Sciences, and especially in Biology” who also had “an interest in education and sympathy with the so-called Nature Study for young people.”23

Given Hooper’s commitment to the life sciences and his progressive educational ideals, it is no surprise that he would be interested in founding a marine biology lab under the auspices of the Brooklyn Institute. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden, founded by the Institute two decades later, would have a dual mission of research and instruction, with a strong connection to Brooklyn’s schools — including programs of nature study. The Biological Laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor was engaged in a similar project.24 Hooper himself taught there during the Laboratory’s first few years, which suggests he was strongly committed to the project.25 Herbert W. Conn, who was the Biological Laboratory’s director for most of the 1890s, described its mission and goals in an article in The American Naturalist in 1895. Conn saw an important contrast between Cold Spring Harbor and the other “marine laboratories on our coast.” While the others were primarily sites of research, the Biological Laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor was different. “The Brooklyn Institute itself is a school of public instruction,” he noted, “and the biological school which it organized naturally assumed from the very outset more of the character of a school of instruction than one of research.”26

Conn had gone into more detail on this subject in an article in Science a few years before, contrasting Cold Spring Harbor with Woods Hole. He emphasized the success of the Woods Hole model for doing biological research. Woods Hole, however, like most other “marine laboratories on our coast” catered primarily —though not exclusively — to those engaged in independent research. The Biological Laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor had a complementary mission, orienting itself toward “students rather than…investigators,” although it was certainly true that independent research was being done at the Biological Laboratory and there were plans to expand in this area. The students who formed the Biological Laboratory’s main clientele included medical students, undergraduates, and “general students” who needed “practical knowledge of biology” for whatever reason. A significant proportion of these students were public school teachers. Conn was very aware of the changes in science education that were taking place in “our public schools,” and noted that “the teacher who is in especial demand is the one who has had practical knowledge of his subjects rather than simple book-knowledge.” Here Conn echoed the then-common call to learn directly from the natural world — as Louis Agassiz had famously put it: “study nature, not books.” Teachers who had had such training, Conn went on, would be better equipped to engage in “the better type of teaching which is rapidly forcing its way into our schools.”27

Conn and other contemporary observers also emphasized the summer resort atmosphere that the Biological Laboratory had in common with other marine laboratories. It was not only a “delightful place to spend the summer,” with “bathing, boating, fishing,” and so on, but also a place where a young student had “a chance for acquainting himself with living nature and the living principles of biological science.”28 The area’s summer watering hole quality, in other words, offered much the same thing to adult students as “nature study” did for children: a chance to immerse themselves in nature and learn — at a much more advanced level, of course — at the same time. An article similar in focus to Conn’s in Scientific American echoed his description of the lab’s atmosphere. Students immersed themselves in their studies in the morning, and “the latter parts of the day are devoted more or less to bathing, boating…or to rambles in the tempting woods…Sometimes we have an evening of college songs, jolly, rollicking and care-dispelling as nothing else can be.” This article’s author, though, unintentionally pointed to another way in which the Biological Laboratory’s mission was very much a Brooklyn Institute kind of project. “Once a week, an evening lecture, semi-popular in its character, is given, and to this residents and summer dwellers or visitors to Cold Spring Harbor are invited.”29 The lab, in other words, was regularly offering scientific content to whoever among the lay public might be interested.

The papers of Charles Davenport, who took over from Conn as the director of the Biological Laboratory in 1899, offer more detailed insights into who these early students were and what they hoped to achieve through a summer or two at Cold Spring Harbor. Because the Biological Laboratory was small and its organization informal in this period, prospective students often wrote directly to Davenport to request information about the lab’s offerings or apply to take a course. They were typically secondary school teachers or university students intending to become teachers, and their descriptions of their own training and experience reflected the ongoing shift from older categories used to describe life-science pedagogy to newer ones like “high school biology.” One student, for example, wrote to Davenport in April of 1898 about attending the lab during the summer, and described himself as a college student “studying with the intention of teaching general biology later.” His training in biology had been “meager” thus far, “though I have had somewhat of botany and entomology but not much.”30 Another prospective student, already a high school teacher, described how she might “be called upon to teach zoology next year,” and was thus interested in a basic course.31 Another described herself a high school “instructor in botany.”32 That a high school would have faculty members teaching only (or primarily) botany or zoology reflected the older categories of the nineteenth century. But that one of the same cohort of Cold Spring Harbor students would be planning on teaching “general biology” in the future reveals the shift in how educators, and future educators, thought about the life sciences.

Indeed, part of the course offerings for these students included “nature study.” This subject, with its emphasis on observing and understanding the relationships between organisms, was not just for children — current and future teachers could also benefit from it before going on to teach it themselves. A teacher at the Boys’ High School in Brooklyn, Roy S. Richardson, was recommended by Hooper to teach this course. A similar course was being offered at Wood’s Hole, and Hooper and Richardson both thought that it could be improved upon at Cold Spring Harbor. According to Hooper, Richardson had taken the Wood’s Hole course the “year that it did not prove a success.” Richardson’s criticisms were that “there was no real observation work done and no connection between” the various subsections of the course. A good nature study course, the criticism implied, needed to involve an exploration of the connections among forms of life — one of the basic ideas undergirding the field of biology. Richardson proposed to do precisely this, “suggest[ing]” to Hooper that “such a course might be laid out so as to cover both insects and plants and their mutual relations, with some slight reference to relations between birds on the one hand and plants and insects on the other.” Richardson had “a large acquaintance among the teachers of Brooklyn and Manhattan,” some of whom would surely be interested in taking such a course.33

The students hoped to receive training in pedagogy as well as biology. Laura Brownwell of Brooklyn, for example, wrote to Davenport in the spring of 1898 to express interest in “High School Zoology” and “collecting expeditions,” i.e. collecting specimens for later classroom or research use. She was “specially desirous of hearing your lectures to get your method of conducting a high school course.”34 Brownwell had a letter of support from Henry R. Linville, founder and head of the biology department at Clinton DeWitt High School in Brooklyn; Linville was well known as an advocate for the new, progressive style of high school biology teaching. Linville noted that Brownwell had studied previously at Woods Hole; after discussing her qualifications, he changed direction slightly to let Davenport know that he had written to the school superintendent at length about “about the laboratory and the use grammar school teachers might make of our high school course.”35 Not only was the Biological Laboratory offering instruction for high school teachers on how to teach biology, as well as on the subject of biology itself — Davenport’s contacts within the New York City School system were also considering how to make use of the resources within their reach, including the courses offered at the Biological Laboratory, to expand biology education within the New York school system. In other words, as Maurice Bigelow of the Teachers’ College at Columbia put it in 1902, Cold Spring Harbor had a “mission of its own in relation to teachers who are engaged in public school work.” While places like the Marine Biology Lab at Wood’s Hole were focused more on research, the Biological Laboratory was meeting the obvious “demand for instruction of high school teachers and elementary students elsewhere.”36

Conclusion

The first decades of the Biological Laboratory’s history shed light on an important period in the history of biology as a discipline and the history of science education in the United States. Biology was coming into its own as a discipline in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Work done marine research stations like Woods Hole, in Massachusetts, was key to biology’s development as a scientific field. But the influence of biology did not end there. Progressive educational reformers put a lot of work into figuring out how to teach this subject in secondary schools and how to train teachers to teach it. Biology teaching in public schools was linked to progressive politics and a desire to address social problems that were believed to be related to urbanization and mass immigration.

Thus, when the Brooklyn Institute, under the direction of Franklin Hooper, decided to create a marine biology laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor, the Institute’s plans were shaped by the educational and scientific currents of the day. The Institute’s educational mission and Hooper’s commitment to both science and teaching resulted in a marine laboratory closely connected by personal and professional ties to Brooklyn and its schools and oriented more toward teacher training than advanced research.

With time, this would change. The Biological Laboratory, located right next door to the Carnegie Institution’s research-focused Department of Genetics, ultimately shifted the balance of its activities from teaching to research. At the same time, the fact that we know that Cold Spring Harbor ended up as a research institution does not mean that its early decades are not worth exploring — they offer us a rich portrait of an important moment in the history of science and American society at the turn of the twentieth century.

[1] BIAS Series 2, Box 2, Folder 1, C. Stuart Gager to Davenport, January 4, 1915. Citations in this paper are abbreviated as follows: BIAS Series 2, Box 2, Folder 1 is abbreviated as BIAS 2/2/1.

[2] BIAS 2/2/1, Davenport to Gager, January 6, 1915.

[3] BIAS 2/2/1, Crittenden to Gager, January 13, 1915.

[4] BIAS 2/2/1, Robert Woodward to Davenport, January 8, 1915.

[5] Jan A. Witkowsky, The Road to Discovery: a short history of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2016), 14-15. Other accounts of Cold Spring Harbor’s history also focus more on the laboratory’s long-term growth and development, in which the character and context of the Biological Laboratory as it was in the 1890s is not the focus of attention. See for example Elizabeth L. Watson, “Long Island Born and Bred: The Origin and Growth of Cold Spring Harbor,” Long Island Historical Journal 2, 2 (Spring 1990): 145-162, and Houses for Science: A pictorial History of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press, 1991), esp. Chapter One. Cold Spring Harbor is not the only marine biology research laboratory whose early focus on teaching has gone underemphasized. As Keith R. Benson has noted, this is a common feature of histories of such institutions. Keith R. Benson, “Why American marine stations: the teaching argument,” American Zoologist 21, 1 (1988): 7-14.

[6] “The Brooklyn Institute’s New Home,” Scientific American 76, 25 (June 19, 1897): 390.

[7] S., “The Brooklyn Institute,” Science 12, 296 (Oct. 1888): 159-160.

[8] “The Brooklyn Institute and Political Science,” Science 19, 485 (May 20, 1892): 282.

[9] “The Brooklyn Botanic Garden,” Science 31, 795 (March 25, 1910): 452.

[10] Frank J. Cavaioli, “Chartering the New York State School of Agriculture on Long Island,” Long Island History Journal 21, 1 (Fall 2009)

[11] Philip J. Pauly, “The Appearance of Academic Biology in Late Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the History of Biology 17, 3 (Autumn 1984): 369-397, 371.

[12] Philip J. Pauly, Biologists and the Promise of American Life: from Meriwether Lewis to Alfred Kinsey (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 148-149.

[13] Pauly, Biologists and the Promise of American Life, Chapter Six, quote p. 154.

[14] Philip J. Pauly, “The Development of High School Biology: New York City, 1900-1925,” Isis 82, 4 (Dec. 1991): 662-688, 665-667.

[15] Pauly, “High School Biology,” 665; Philip J. Pauly, “The Appearance of Academic Biology in Late Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the History of Biology 17, 3 (Autumn 1984): 369-397, esp. pages 370-372.

[16] Pauly, “High School Biology,” 675.

[17] Ronald P. Ladouceur, “Ella Thea Smith and the Lost History of American High School Biology Textbooks,” Journal of the History of Biology 41, 3 (Fall 2008): 435-471.

[18] Henry R. Linville et al., “The Practical Use of Biology,” School Science and Mathematics 9, 2 (Feb. 1909): 121-130.

[19] Anon., review of H. W. Conn, Physiology and Health, Journal of Education 84, 2 (July 1916): 49. See also Conn’s extended discussion of the role of biology in education in H.W. Conn, “Modern Biology as branch of Education,” Science 9, 211 (Feb. 1887): 168-170.

[20] Sally Gregory Kohlstedt, “Nature, not books: scientists and the origins of the nature-study movement in the 1890s,” Isis 96, 3 (September 2005): 324-352; Kohlstedt, “ ‘A better crop of boys and girls’ : the school gardening movement, 1890-1920,” History of Education Quarterly 48, 1 (Feb. 2008): 58-93.

[21] Pauly, “High School Biology,” 665, 673.

[22] Franklin W. Hooper, “Industrial Museums for Our Cities,” Proceedings of the American Association of Museums v. 7-8 (1913-1914), 6-10. Quote p. 7. Via HathiTrust.

[23] CIW 39, Folder: Hooper, Franklin, 1900-1902, Hooper to Davenport, Feb. 25, 1902.

[24] For the Botanic Garden’s educational mission, see “The Brooklyn Botanic Garden,” Science 31, 795 (March 25, 1910): 452 and “The Brooklyn Botanic Garden,” Scientific Monthly, 5, 4 (Oct. 1917): 381-383.

[25] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles Benedict 1912-1917 / Davenport to Walter F. Crittenden, January 15, 1915.

[26] H. W. Conn, “The Cold Spring Harbor Biological Laboratory,” The American Naturalist 29, 339 (March 1895): 228-234, quote p. 231.

[27] Herbert W. Conn, “Report of the Summer School of the Brooklyn Institute for the Season Just Closed,” Science 20, 502 (Sept. 16, 1892): 157-159.

[28] Herbert W. Conn, “Report of the Summer School of the Brooklyn Institute for the Season Just Closed,” Science 20, 502 (Sept. 16, 1892): 157-159.

[29] A. D., “The Biological Laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, N. Y.,” Scientific American 73, 7 (August 17, 1895): 99.

[30] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles B. 1898 / C. A. Crowell to Davenport, April 9, 1898.

[31] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles B. 1898 / Mary E. Van Deventer to Hooper, April 20, 1898.

[32] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles B. 1898 / Marie L. Berier to Davenport, June 13, 1898.

[33] CIW 39 / Hooper, Franklin, 1900-1902 / Hooper to Davenport, January 13, 1902, Hooper to Davenport, January 23, 1902.

[34] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles B. 1898 / Laura Brownwell to Davenport, June 13, 1898.

[35] CIW 24 / Davenport, Charles B. 1898 / H. R. Linville to Davenport, June 14, 1898; on Linville’s biology advocacy see Henry R. Linville et al., “The Practical Use of Biology,” School Science and Mathematics 9, 2 (Feb. 1909): 121-130, and Pauly, “High School Biology,” 669.

[36] CIW 39 / Hooper, Franklin, 1900-1902 / Maurice A. Bigelow [of Teachers College, Columbia University] to Davenport, April 3, 1902.

[aria-label=”Ask Us”] { display: none; }