Cancer and Cronyism at the NIH: Norton Zinder and the Special Virus Cancer Program

By Antoinette Sutto, Robert D. L. Gardiner Historian, sutto@cshl.edu

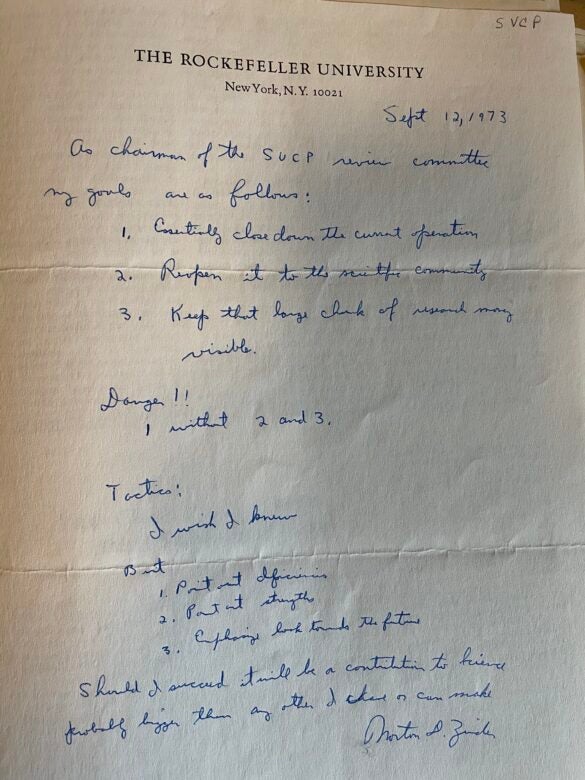

Zinder had three goals, and they did not bode well for the continuation of the program as it currently stood:

(1) Essentially close down the current operation

(2) Reopen it to the scientific community

(3) Keep that large chunk of research money visible

Under “Danger!!” he noted that the worst outcome would be to achieve the first, closing down the program as it currently stood, without the second two. His goal, in other words, was to keep the program’s money available for researchers while putting paid to the SVCP itself. As he noted at the bottom of the page, “Should I succeed it will be a contribution to science probably bigger than any other I have or can make.”1

The Special Virus Cancer Program, later simply the Virus Cancer Program (VCP), was launched in 1964. It was part of the NCI, which in turn had been founded in 1937 to research causes of and treatments for cancer and promote cancer research. The NCI had supported research into the relationship between viruses and cancer since the early 1960s, and the SVCP was part of that general effort.2

The SVCP did have some peculiarities, however. “From the start [it] relied heavily on the planning techniques used in space and military programs, and, for a biological undertaking, it has made similarly lavish use of resources.”3 The problem with all this was that by the early 1970s, the program had not produced the breakthroughs in treatment, or even the advances in basic knowledge, that its founders and funders had expected. More than this, the way the program was run and how its funds were awarded frustrated large numbers of scientists. This was the background for the appointment of the Zinder Committee to review the Special Virus Cancer Program in March of 1973.

Historians of science have examined changes in federal cancer research policy in the 1960s and 1970s from a number of directions. Soon after the “war” was launched, Stephen Strickland and Richard Rettig dove into the political process of how the Cancer Act of 1971 itself came into being. There is also a great deal of scholarly literature focusing on the cultural history of cancer and campaigns of prevention and treatment. James Patterson, for example, has placed Nixon’s War on Cancer within the long story of the cultural history of cancer in the United States.4 Siddhartha Mukherjee situates the Nixon-era “War on Cancer” in an even larger cultural context, describing connections between fears of cancer and shifts in how Americans understood threats to themselves and their society. In this immediate context, laypeople such as the famous cancer activist Mary Lasker and organizations like the American Cancer Society that were crusading for increased funding for cancer research had an easier road ahead of them. In addition to this, the Nixon administration wanted to change how scientific research was managed. Nixon neither liked nor understood the idea of basic, open-ended research and was all for taking control of research planning away from people he termed “nuts” and giving it to, as Mukherjee put it, “a new cadre of scientific bureaucrats” who would “bring a new discipline and accountability to science.”5 Robin Scheffler has argued that the controversy over the SVCP and the activities of the Zinder Committee show scientists in revolt against the centrally managed, contract-focused research program of the NCI, because they feared it would undermine what they saw as more autonomous, independent grant-based research. They were affected by changes in federal research strategy, but they were also the experts whose opinions and cooperation were necessary to the enterprise, and they were able to use the value of their own scientific expertise and their access to the machinery of federal bureaucracy to fend off what they saw as government intrusion into scientific independence.6

The material in the Zinder Collection at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives highlights the importance of chronology – specifically, the relationship between changes in how scientists thought about cancer and the timing of political changes in the United States.7 This essay argues that a close look at this episode in the history of federal cancer research shows how a specific model for cancer causation interacted with larger cultural and political changes to produce a miniature crisis in the world of biological and biomedical research. The virus model suggested an easy-to-target model for the cause of cancer — viruses — and a relatively simple fix: vaccines. Biomedical researches found themselves caught in a situation where a lot had been promised politically — the SVCP was compared to the moon landing, and many lay people and members of congress had the impression that a cure for cancer could be as simple as finding the right talent and putting enough money into the effort. The basic research that would have allowed this was lacking, however, and the enterprise as a whole was poorly managed. It ended up becoming a “big science” nightmare for biologists. The existence of the SVCP was an artifact of a specific scientific model being prevalent at a specific time; the program itself contributed to a sense of crisis among researchers, a feeling of being at a big turning point, and the Zinder Committee’s review of the program allowed a way for scientists to articulate concerns about where their field was headed in a larger sense. As such, the episode illustrates an important moment in the history of modern biological research.

*

The SVCP was launched in the mid-1960s, during the post-war period of federal largesse in terms of basic research funding. Within a few years after the program’s founding, however, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a move on the federal government’s part toward demanding more immediate returns on investment in scientific research. This was a sharp contrast to the immediate post-war period, when molecular biology research had been supported with the assumption that there would be significant practical gains at some point in the future, even if those gains were not easy to predict or direct at the moment. The social movements of the 1960s also played a role in this shift, as activists and progressive organizations called for more socially useful research, with immediate benefits for ordinary people.8 Americans’ expectations of what the federal government could, and should, do in terms of safeguarding public health and preventing disease had expanded. The 1960s and 1970s were, for example, the era of the first pieces of modern environmental protection legislation, such as the Clean Air Act, first passed in 1963 and amended at various points in the later 1960s and 1970s. Less pure motives were also at work. As noted above, President Nixon had no great respect for scientists, but he was interested in “outflank[ing] Senator Ted Kennedy, a potential presidential candidate who was then leading the Lasker forces,” i.e. the alliance of activists and organizations spearheaded by cancer research activist Mary Lasker. Their goal was increased funding for targeted research into cancer treatments.9 Changes in management practices within the federal government also played a role. In the late 1960s, “systems analysis” expanded from defense into other areas of the federal government.10 This included the federal government’s cancer program.11 Systems analysis is a goal-directed management method that involves setting specific targets and mapping out in extensive detail what steps must be taken to achieve these targets with maximum efficiency and how to carry out these steps. It presupposes large organizations, large budgets and large staffs.

Related to the federal government’s interest in systems analysis – but nevertheless distinct – was the rise of “big science.” The term “big science” was coined by Alvin Weinberg, a nuclear physicist, in 1961. Weinberg applied the term to the massive projects in physics and engineering that typified the Cold War-era scientific competition with the Soviet Union. He argued that big science had caused a series of problems for the practice of science itself. The first of these was that the flip side of massive public funding was a need to appeal to the public. As a result, “Big Science…thrives on publicity. The inevitable result is the injection of a journalistic flavor into Big Science which is fundamentally in conflict with the scientific method.” This blurred the line between science writing and journalism, and “issues of technical merit tend to get argued in the popular, not the scientific press,” or in congress rather than in universities. In Weinberg’s view, this led to prominence for the showy rather than the thoughtful. The second big problem was that the abundance of funding led scientists to throw money at problems rather than thinking up a way to reframe the problem so that it might be solved with the resources at hand — “spending money instead of thought.” Big science also created a problem of too many administrators, or a too-large ratio of administrators to working scientists. “Unfortunately, science dominated by administrators is science understood by administrators, and such science quickly becomes attenuated, if not meaningless.” He also noted the prospect of “pet projects” getting special treatment as far as funding was concerned and “the dangers of creating a political ‘in’ group of scientists who will keep worthy outsiders from the till.”12 Many of Weinberg’s criticisms of big science would prove to be prescient as far as the NCI in the early 1970s was concerned. However, it is important to emphasize that Weinberg was not categorically against big science. Ironically, in his more extended treatment of the subject, published in the late 1960s, he argued that given their relevance for human health, molecular biology and biomedical research were good candidates for large, complex research endeavors. He thought that “the biomedical sciences can be force-fed, even more than they are now being force-fed.” More money would attract the best scientific talent and support the best research.13

All of this together – cultural, political and administrative developments – formed the context for the review of the SVCP that took place in 1973-1974. The review committee consisted of about a dozen scientists, headed by Norton Zinder. Zinder and his colleagues dug into the progress and results of the program, made site visits, and interviewed people who were involved in awarding the program’s outside grants and contracts. They also spoke on the phone with and received letters from researchers who had had to do with the program in some capacity and whose reactions were, on the whole, negative.

The report that the Zinder Committee issued in the spring of 1974 was regarded as “a stinging attack.”14 According to science journalist Barbara Culliton, who reported on the committee’s criticisms of the program and their recommendations, the Zinder committee had “managed to shake up a lot of people at NCI, and there is evidence that many of its recommendations will be put into effect, as nearly everyone agrees they should.”15 The subcommittee tasked with drawing up a response to the Zinder Committee’s report was more circumspect, emphasizing that the goal of the review process had been to consider the program on its “operational level,” and that as a result, Zinder and his colleagues had not discussed “the substantial, one might well say impressive, accomplishments of the Special Virus Cancer Program.” 16 Other voices from within the NCI were blunter, “claim[ing] that the review committee seriously exaggerated the problems and that the committee itself hadn’t really understood the way the program operates.”17 In the end, the NCI did commit — at least on paper — to addressing the organizational and conflict of interest problems that the Zinder Committee described in their report.

What specifically had the Zinder Committee found? First of all, they said that the basic assumption behind the program scientifically sound, arguing that “the scientific rationale for an intensive study of the role of viruses in human cancer is well founded…it is not only the opinion of this committee but of the scientific community at large that a virus etiology for some human cancers is probable.”18 The problem was with how the program was being administered – and with one of its fundamental assumptions, that “force-feeding” an area of research, to borrow Weinberg’s term, could get results. The Zinder Committee’s critiques revealed the concerns that academic scientists had in the face of changing federal funding priorities and management strategies, as well as their fears of “big science” as applied to biology.

The criticisms that the Zinder Committee (and other scientists) made at the time can be grouped under two headings. The first had to do with the philosophy of the program, the state of current research and the general effects that the SVCP and the Cancer Program had on the process of doing science. Although it might seem counterintuitive to non-specialists, scientists argued that throwing a lot of money and effort on solving a very particular narrowly-defined problem was not necessarily the best way to gain the knowledge needed to solve it. As biochemist Arthur Kornberg wrote to Nixon’s cancer program advisor Benno Schmidt in 1974, “narrowing the focus of research so sharply limits the serendipitous discoveries which have dominated the modern history of medical research.”19 The “War on Cancer,” including the SVCP, was sometimes compared to the moon landing — that is, an all-out effort at enormous expense in which American ingenuity and know-how were expected to win the day and deliver spectacular results. Virologists and other experts were skeptical, however.20 Jim Watson, for example, had little patience with the moon landing metaphor for the federal government’s “War on Cancer” in the 1970s. A more realistic ‘moonshot’ comparison, he told the Boston Globe in 1978, would be an attempt to land a man on the moon in the 1920s before the invention of modern rocket technology, by giving contracts to cannon-makers and ladder experts and a lot of administrators — but with no support for basic rocket science.21 Jim Watson’s quip to the Boston Globe was not the only such statement. The Wall Street Journal described unnamed scientists as saying that “this ‘targeted research’…smacks of a false analogy to the moon shot program, where the goal was clear and the technology was available. Yet not only do scientists not know the best way to ‘conquer cancer,’ they are not even sure what cancer itself might be. (Some say that the name covers dozens, and maybe hundreds, of diseases.) Furthermore, the programmed approach leaves little room for the chance that new and more productive lines of research might develop….[scientists] say the contract worker simply won’t have the flexibility to follow up chance discoveries, and these are the heart of scientific breakthroughs.”22 The Zinder Committee’s report made this argument as well, and in no uncertain terms: Neither when the SCVP was started nor at the present was there “sufficient knowledge to mount such a narrowly targeted program. Basic ignorance of the mechanism involved in the cancer process…is so profound that it is difficult to be certain where to begin, much less organize a focused attack.”23 Finally, the program was having deleterious effects on scientists’ research trajectories and causing promising work to go funded. Speaking of the NCI’s cancer program in general, Arthur Kornberg said that he knew of “many investigators who now choose cancer problems because they will be funded over problems which they judge more important and soluble…in my own field of DNA research most of the basic insights in the structure and function of chromosomes and genetic material have come from work on bacteria and bacterial viruses. Yet today first-rate young investigators working in this fertile area are denied NIH support and a university appointment while second-rate colleagues working on a cancer virus get both…in doing so we starve the goose that has been laying the golden eggs of basic research from which will hatch essential components needed to solve the cancer puzzle.”24

The second group of criticisms were directed at the bureaucratic structure of the SVCP, its effects on how research was funded and the quality of work that resulted. The SVCP awarded its research funds not in the form of peer-reviewed grants but rather through contracts. There were several problems associated with this system. The first was that the review system for awarding contracts was sloppy and its fairness undermined by conflicts of interest. The Zinder report described how a significant proportion of the scientists tasked with reviewing contracts “felt a great deal of unease at the lack of critical review.” Compared to their work on grant study sections, where “the peer review was serious and stringent,” the review process for contracts was “perfunctory.”25 One reviewer, a pediatrics professor at the UC San Diego medical school, called the whole process a “complete farce” and added that “occasionally, we were asked to review a project in a field that no one on the committee had special knowledge of, and with few exceptions, the caliber of the work proposed was extremely poor. I would guess that more than half of the requests for which we granted money would have been rejected outright” in a typical grant review. “A great deal of research of very questionable merit is being supported” by the contract program, he concluded.26

Even projects for which it made sense to contract with industry were not necessarily successful. Dr. W. J. Joklick of the Duke University Medical Center described his experience with contracts in a letter to Zinder in August of 1973. He was not a contractor himself, but about two years before, the NCI had given a contract to a commercial laboratory nearby to supply him with a strain of the Rous sarcoma virus. What his team received was excellent, but all efforts to obtain more of the same failed. He was skeptical of the contract system in general, telling Zinder that based on his experience with the Rous sarcoma virus, “awarding large contracts for the supply of reagents or for the performance of specialized tests to first rate investigators” made sense “in theory” but “I see no evidence that this has in fact worked out in practice. Such contracts have in general turned out to be extremely expensive with disappointingly small return.”27

Even once it had been determined that a particular contract was not working out as expected, it was difficult to terminate the arrangement. The Zinder committee found that often, contracts were given to those with friendly relationships to the people administering the program, which meant that “when the work is finished or the contractor fails to produce, understandably it becomes difficult to terminate the contract….[Moreover,] an equity is developed in the work of a particular contractor. Failure on his part leads to an attempt to prop up his program with more money instead of more appropriate phasing out or termination. The information we received indicates that it is more difficult to terminate [a] bad contract than an unproductive grant.”28

At least as much of a problem as the contract system was the power of the section chairs. According to the Zinder committee, the basic problem with the SVCP was that the segment chairs had nearly unlimited control over an enormous amount of money, and these funds were not being distributed in a way that effectively advanced the scientific goals of the program. As the committee put it, “the Segment Chairmen have too much power.”29 Who were these segment chairmen? The SVCP had eight segments, each covering a different research area. In charge of each was a chair (who was also an NCI researcher) and a working panel charged with reviewing contracts. In theory, all contracts were supervised by project officers, but it was also possible for a chair to supervise a contract directly.30 Perhaps unsurprisingly, the working groups that evaluated the contracts were chosen by the segment chairs, out of a pool of people mostly known to the chairs, with the result that “their backgrounds and areas of competence tend to coincide with that of the segment chairmen.”31 The roles of segment chair, working group member and project officer (the NCI administrator responsible for a specific contract) could overlap, resulting in a combination of chumminess and vagueness that was the perfect breeding ground for ethical lapses.

Finally, in addition to the dodgy contract review process and the segment chairs’ excess of power, scientists not affiliated with the NCI saw the program as a slush fund for NCI researchers. In a letter he wrote to NCI head Dr. Arthur Upton in 1977, Zinder noted that not only had there been a “widespread feeling” in the early 1970s “that large sums of money were being distributed by the contract mechanism to support people whose research was of questionable quality,” it was also “believed that some scientists at the NCI were using this extramural program to support large scale extensions of their own work.” That is, what appeared to be outside contract research was actually an extension of an individual NCI member’s own research program, paid for SVCP funds. His committee’s investigations “found these beliefs to be essentially true.”32 The Zinder committee’s report put the problem succinctly:

We seem also to have the peculiar situation of NCI staff scientists writing contracts for private industry, the monies of which are used to support their own work. These contracts go for first review to the Segment Chairmen Committee of which they are often members, and then to the working groups, which [they] may either chair or sit on, and which often contain close friends and colleagues. NCI staff scientists also move about from one of these local contractors to another, in what can only be interpreted as an effort to support these contractors. Further comment on such modes of operation should be superfluous.33

The problems that the Zinder Committee and their contacts and correspondents in the biological and biomedical sciences wrote about look a lot like those of a discipline plunging – or being plunged – into Weinberg’s “big science.” The textbook example of big science in the 1960s and early 70s was the space program and the moon landing, and as noted above, this metaphor was used repeatedly to talk about the SVCP, by both its supporters and its critics. “Big biology” had arrived. But unlike physicists and engineers, biologists were not working on massive projects centered around a large piece of technology, like the atom bomb, a particle accelerator or a moon rocket. The aspects of big science that affected life scientists the most were administrative. There was an increase in the use of contracts to fund science by national funding agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the NIH, as well as an uptick in the number of administrators at these agencies.34 The move toward contract-based funding for cancer research was, as noted above, a source of dissatisfaction for many biomedical researchers.

Biologists discussing the SVCP in the early 1970s expressed many of the same concerns as Weinberg had ten years earlier about “big science” in general – top heavy administration, “pet projects,” in-groups, throwing money at problems rather than thinking them through. One colleague, for example, expressed indignation about many scientists’ slide into administrative turf wars and hoped that the Zinder Committee’s work would “get the ball rolling so we can get scientists back into the laboratory working on cancer instead of defending their petty little kingdoms or pet scientific theories.”35 The problem of ‘in groups’ was articulated by W. K. Joklik of the Duke University Medical Center when he described a different contract program in which he was involved, one in which “all[underlined] members of the scientific community, and not only a select in-group, will be able to apply for these contracts.”36 The Zinder Committee Report also noted that that the program had begun with an “in group,” which was not surprising, and it was currently composed of a “somewhat larger in group of investigators…its procedures…are apparently attuned to the benefit of staff personnel and are full of conflicts of interest.”37 A lot of money was being handed out for research projects of doubtful quality and relevance — from the point of view of academic scientists, the SVCP contract program as it existed was a textbook example of throwing money at a problem rather than thinking it through. The size of the research teams supported by the SVCP was also an issue. Joklik argued that in his experience, “once scientific teams have reached an essential critical mass, their size very quickly reaches a limit beyond which their operations become more and more inefficient.”38 Once biology got too big, it became less effective.

An important aspect of big science that lay outside the scope of the Zinder Committee’s activities was the relationship between scientists and the media. The War on Cancer was in part the result of public agitation by people like Mary Lasker and the American Cancer Society. The Nixon administration had a stake in promoting it. And given the seriousness of the disease, the American public was always eager to read about groundbreaking advances in cancer research. The SVCP was implicated in all of this because it was a targeted research initiative that was supposed to produce tangible results fairly quickly. More than this, the virus model of cancer causation that was the intellectual basis for the SVCP raised hopes that the research might produce a cancer vaccine.

The problem was that there was a significant mismatch between how the SVCP and the Cancer Program in general were sold to the public, on the one hand, and on the other, what the people in charge of running it knew that they could deliver. Scientists and administrators working at the NCI or the NIH or otherwise affiliated with the War on Cancer were naturally well aware that given the state of basic cancer research, the prospects of a cure within the next few years were vanishingly small. This led to significant tension between how the program was presented to the public and what those running it knew they could realistically provide, even under the best of circumstances. Occasionally representatives of the program had to backpedal and argue repeatedly that they had never implied that there would soon be a vaccine against cancer — even though, essentially, they had. In his correspondence with Arthur Kornberg, Benno Schmidt said that “no one responsible for the cancer program believes that this is a research effort that can be managed, predicted or targeted, or that a timetable can be fixed or a price tag set. All[underlined] we offer is an accelerated effort.” 39 “Nobody,” he said, “is under the illusion that the cancer problem is one of implementation of known science or that the research needed to advance cancer knowledge can be targeted or planned.”40 In the assessment of the National Cancer Program made by the President’s Cancer Panel, of which Schmidt was the chair, in January of 1973, the committee concluded that “one of our greatest concerns is the risk of inordinately high expectations on the part of the Congress and the public. We must not think of this program as comparable to a moon shot or an atom bomb program.”41 This statement was echoed in a review of the National Cancer Program Plan in 1972:

In its present form, the NCPP could easily be misconstrued as a plan for a total[underlined] attack on cancer, including the treatment of all cancer patients, which would imply a capacity to deal with the enormous problems of inefficiency and inequity now confounding the health care enterprise throughout the country. It is obvious that the NCI was not assigned such a mission, and is in no position to carry it out if it were…If the Congress and the public were to conceive of the NCPP as a total plan designed to mobilize all the institutions, professional practitioners and technicians of our society into a coordinated and rationalized ‘War on Cancer,’ it seems unavoidable that the outcome would be the deepest disillusionment.”42

The problem was that President Nixon himself had publicly made this very comparison to the moon landing in his second State of the Union Address.43 The idea of a war on cancer in which quick and spectacular results were expected was occasionally echoed even by scientists and medical professionals. In 1974, molecular biologist Sol Spiegelman predicted the isolation of a human cancer virus within the next few years, which would be a big step toward a cancer vaccine. A clipping of the article in which his statement appears is among Norton Zinder’s papers, with a note in red felt-tip marker at the top: “Norton who’s not promising a vaccine?” The phrasing suggests that that the clipping was sent with reference to someone’s claim that scientists weren’t promising a vaccine.44 In 1977, the deputy director of the NCI testified before congress that “The National Cancer Program is a response to the urgent wishes of the American people to curb the lethal power of the group of over 100 diseases known as cancer. The goal is to develop the means to reduce the incidence, morbidity and mortality of cancer in man, and ultimately to eliminate all human cancers.” Although not as explicit as Nixon’s comparison to the moon landing, the deputy director’s audience might be excused for thinking that the NCI thought a cure for cancer was within their grasp in the short to medium-term.45 But despite all of this, the committee charged with responding to an early version of the Zinder Committee’s findings, which had been presented in a closed session at the end of 1973, was miffed that the impression had been given that the SVCP was going to make great leaps forward in research. “The fact is,” they wrote, “that the Virus Cancer Program has never considered the virus-cancer problem to be one which would be readily resolved.”46 There was a significant gap, in other words, between how the SVCP and the War on Cancer in general had been presented to the public and the realities of what could realistically be achieved.

Ultimately, the best way to understand the controversy over the SVCP is as a collision between big science, the politics of the late 1960s and early 1970s and – crucially – a specific model of the causes of cancer that was soon to disappear. In the 1960s and early 1970s, it seemed that viruses might be part of the cause of cancer in humans. Over the course of the 1970s, research based on this idea developed into a different model, which would not have been possible without the virus-cancer hypothesis, but which no longer assumed that viruses were a significant cause of cancers in people.47 But in the early 1970s, the virus model was at the peak of its popularity among scientists. Indeed, it seemed even more convincing then than it had when the SVCP program had begun. As immunologist Mathilde Krim wrote to the SVCP’s director, John Maloney, in early 1974,

“It is clear that the scientific environment in which the VCP operates has greatly changed since its first year of operation: it was a situation where funds were needed to be used as an inducement to research in the possible role of viruses in cancer; this environment has evolved to one where the scientific community is broadly convinced that a partial or complete etiologic relationship does indeed exist, and where it is in great need of support to investigate all facets of the problem in animals and man in order to achieve the still elusive understanding of the nature of the etiologic relationship. Thus, not only must the VCP continue supporting a variety of approaches ranging from epidemiology to work on basic molecular events, but competition for funds in this field has become fierce both because of recent scientific developments and the present general funding strictures in bio-medical research.”48

Had this shift in scientists’ understanding of how cancer worked come at a different time, the SVCP would not have had the importance than it did – and would not have been there to serve as a focus of frustration for scientists angry and apprehensive about changes in the federal government’s approach to research funding, a change that took place on a broad scale and not simply with regard to cancer research. More than shifts in funding structures and administration may have been at work, however. The reactions that the SVCP provoked among molecular biologists, biochemists and medical researchers were at times very concrete, as just above. But there were also things that were harder to pin down. In one of his letters to Nixon’s cancer advisor Benno Schmidt, Arthur Kornberg said that his colleagues held varying views about the program. “I find it difficult to convey in writing fragmentary data, a host of impressions and subtle feelings,” he told Schmidt.49 The controversy over the SVCP and the NCI came at the same time as what geneticist and molecular biologist Matthew Meselson described to Horace Judson as “the great dispersal” in the field of molecular biology. Judson’s interviewees, all specialists in the field in the 1960s and 1970s, described a change in culture around this time in which the field seemed to them to become less focused and more crowded. Researchers described an impression that scientific problems were becoming less ambitious and more specialized, and because there were more and more people in the field, there was “more ruthless competition and a new alacrity in publication.”50 For a lot of researchers, the NCI’s apparent shift toward contract funding and increase in administrators combined with the internal changes in the field that Judson’s interviewees described probably combined to create a sense that they had reached a turning point and actions taken now would likely have a significant effect on how the future looked. Zinder described his hopes for the effects of the committee’s work on the NCI in fairly heroic terms, as if they were doing battle with a behemoth. In a letter to a colleague in May of 1974, he noted that it “was only because of the unselfish aid of many scientists that we may have put a dent in the operation of the VCP and the Cancer Program in general.”51

Where does this leave us? Despite the high drama that the SVCP and the Zinder Committee’s review provoked, the practical effects on the SVCP and the NCI were limited. Initially, Zinder expressed hope that “a beginning has been made.” He and the committee had “unsettled the system a bit, if nothing else.”52 He was less optimistic a few years later. The NCI had had time by this point to put the committee’s recommendations into practice, but little had changed. “For some time now,” Zinder noted,

I have been approached by scientists both in and out of the program saying that the abuses of power that we found four years ago are as bad as ever…In addition, there were some simple changes that we requested which, although mentioned in the text of our report, were not even listed in the recommendations that have not been put into effect, although we were assured that they would be. 53

*

The controversy over the SVCP and the Zinder Committee’s review of it is significant for several reasons. As an example of scientists navigating the potentially treacherous waters of federally funded “big science” it highlights the complexity of the relationship between biologists and agencies like the NIH. Scientists needed the funding the government could provide, but were suspicious when funds seemed to be given out in a way that violated their sense of what was worthwhile research and who was a deserving recipient. The controversy also shows the practical effects of a specific cancer paradigm – that a viral theory of cancer suggested the immediate solution of a vaccine fit perfectly into the “moon landing” understanding of the War on Cancer: a concrete idea that seemed reachable with enough money and manpower. Timing, in other words, was important. Had the internal development of theories of carcinogenesis and the replacement of one paradigm by another tracked differently with the external political narrative, both the history of the SVCP and the opposition to it would have unfolded very differently. Finally, this controversy in the early 1970s points forward to another conflict, or potential conflict, between molecular biologists and the federal government that took shape a few years later: the regulation – or not – of recombinant DNA research carried out with federal funding.

Notes

1 Norton Zinder Collection (NZC), Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, handwritten note on SVCP dated Sept. 12, 1973.

2 “National Cancer Institute (NCI),” via the National Institutes of Health, https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-cancer-institute-nci, accessed October 6, 2021.

3 Nicholas Wade, “Special Virus Cancer Program: Travails of a Biological Moonshot,” Science 174, 4016 (24 December, 1971): 1306-1311.

4 Stephen Strickland, Politics, Science and Dread Disease: A Short History of United States Medical Research Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972; Richard A. Rettig, Cancer Crusade: The Story of the National Cancer Act of 1971 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977); James T. Patterson, The Dread Disease: Cancer and Modern American Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

5 Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (New York: Scribner, 2010), 182-183.

6 Robin Wolfe Scheffler, A Contagious Cause: The American Hunt for Cancer Viruses and the Rise of Molecular Medicine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), Chapter Eight.

7 Michel Morange, “From the Regulatory Vision of Cancer to the Oncogene Paradigm, 1975-1985,” Journal of the History of Biology 30, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 1–29; Michel Morange, The Black Box of Biology: A History of the Molecular Revolution, trans. Matthew Cobb (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), Chapter Eighteen.

8 Doogab Yi, The Recombinant University: Genetic Engineering and the Emergence of Stanford Biotechnology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), pp. 6-8.

9 Patterson, Dread Disease, 248-249.

10 Guy Black, “Systems Analysis in Government Operations,” Management Science 14, no. 2 (October 1967): B41–58; Alain Enthoven, “How Systems Analysis, Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, or Benefit-Cost Analysis First Became Influential in Federal Government Program Decision Making,” Journal of Benefit Cost Analysis 10, no. 2 (2019): 146–55.

11 Barbara J. Culliton, “Biomedical Research (II): Will the ‘Wars’ Ever Get Started?,” Science 181, no. 4103 (September 7, 1973): 921.

12 Alvin M. Weinberg, “Impact of Large-Scale Science on the United States,” Science 134, no. 3473 (July 21, 1961): 161–64.

13 Alvin M. Weinberg, Reflections on Big Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967), 106.

14 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, xerox of Colin Norman, “Cancer research runs into trouble,” Nature 248, April 5, 1974, pp. 465-466.

15 Barbara J. Culliton, “Virus Cancer Program: Review Panel Stands By Criticism,” Science 184, 4133 (April 12, 1974): 145.

16 NZC, Series: Rockefeller University, Box 1, Folder: 1974, Harold Amos, draft report of review of Zinder report, June 10, 1974.

17 Daniel S. Greenberg, “NSF Boosts Use of Contracts for Research / Cancer program is attacked by study,” Change 6, 4 (May 1974): 54.

18 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 157, Folder: [unlabeled, “Chemistry search” written on front cover], Report of the Ad Hoc Review Committee (Zinder Committee) for the Special Virus Cancer Program. Hereafter cited as “Zinder Committee Report.” Quote on page 3.

19 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Kornberg to Schmidt, June 24, 1974.

20 Nicholas Wade, “Special Virus Cancer Program: Travails of a Biological Moonshot,” Science 174, 4016 (24 December, 1971): 1306-1311.

21 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 173, Folder: unlabeled, “War on cancer: frustration splits ranks,” Boston Globe, April 24, 1978.

22 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, “Fighting the Cancer War,” The Wall Street Journal, August 1974.

23 Zinder Committee Report, 6.

24 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Kornberg to Schmidt, June 24, 1974.

25 Zinder Committee Report, 11.

26 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder: Rev. Cancer, Jerry Schneider, Assoc. Professor of Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego Medical School, to Zinder, 13 August 1973.

27 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder: Rev. Cancer, Dr. W. K. Joklik, Duke University Medical Center, to Zinder, August 8, 1973.

28 Zinder Committee Report, 10.

29 Zinder Committee Report, 10.

30 Wade, “Travails of a Biological Moonshot,” 1307.

31 Zinder Committee Report, 11.

32 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder [unlabeled, with “Dr. Zinder” written on the cover], Zinder to Dr. Arthur Upton, September 12, 1977.

33 Zinder Committee Report, 16.

34 Greenberg, “Science Policy: NSF Boosts Use of Contracts for Research / Cancer Program Is Attacked by Study.”

35 NZC, Series: Rockefeller University, Box 1, Folder: 1974, James Whitman to Zinder, April 2, 1974.

36 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box: 149, Folder: Rev. Cancer, Joklik to Zinder, August 8, 1973. Emphasis in original.

37 Zinder Committee Report, 13.

38 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box: 149, Folder: Rev. Cancer, Joklik to Zinder, August 8, 1973.

39 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Schmidt to Kornberg, July 11, 1974. Emphasis in original.

40 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Schmidt to Kornberg, June 18, 1974. Entire sentence underlined in original.

41 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, President’s Cancer Panel, assessment of the National Cancer Program January 25, 1973, page 14.

42 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Report of Ad Hoc Review Committee of the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, Assessment of National Cancer Program Plan, pages 12-13. Emphasis in original.

43 Daryl E. Chubin and Kenneth E. Studer, “The Politics of Cancer,” Theory and Society 6, 1 (July, 1978): 57.

44 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: [unlabeled], Clipping “Cancer Viruses” from The Nation Tuesday, March 26, 1974.

45 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder: [no label, “Dr. Zinder” written on the front cover], NCP special communication, August 17, 1977, copy of testimony of Guy R. Newell, M.D., Deputy Director of the NCI, before the Intergovernmental Relations and Human Resources Subcommittee of the House of Representatives, page 1.

46 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder: Rev. Cancer, Comments on the report of the ad hoc review committee of the Virus Cancer Program, January, 1974.

47 Daniel T. Kevles, “Pursuing the unpopular: a history of courage, viruses and cancer,” in Robert B. Silvers, ed., Hidden Histories of Science (New York: New York Review of Books, 1995), 69-109; Morange, “Oncogene Paradigm”; Morange, Black Box of Biology, Chapter Eighteen.

48 NZC, Series: Rockefeller, Box 1, Folder: 1974, Mathilde Krim to John Maloney, July 11, 1974, page 2.

49 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 135, Folder: Ad Hoc Advisory Committee for Special Virus Cancer Program, 1973, Kornberg to Schmidt, July 16, 1974.

50 Horace Judson, The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology. Commemorative Edition. (Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2013), 925-7.

51 NZC, Series: Rockefeller, Box 1, Folder: 1974, Zinder to S. R. Wagle, May 29, 1974.

52 NZC, Series: Rockefeller University, Box 3, Folder: unlabeled, Zinder to J. M. Price, May 16, 1974.

53 NZC, Series: Government Activities, Box 149, Folder: [no label, “Dr. Zinder” on front cover], Zinder to Arthur Upton, September 12, 1977.

[aria-label=”Ask Us”] { display: none; }