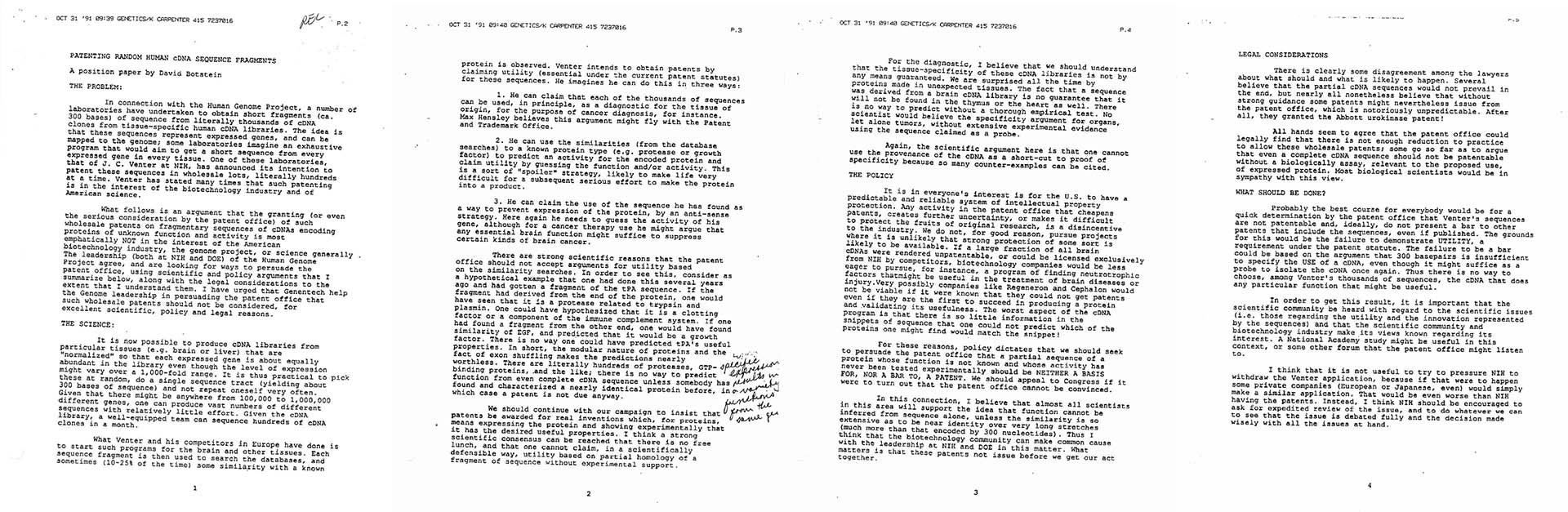

One of the main reasons Dr. Watson resigned from his position as Director of the National Center for Human Genome Research in 1992 was his disagreement with Bernadine Healy (who was then Director of NIH) over the right of scientists and the biotechnology industry to patent gene sequences. Watson believed that human genes were a product of nature, and therefore not patentable. Further, he believed that the Human Genome Project was intended to benefit all of mankind, and that it was unethical for private entities to profit off of the science that was being funded by the project. Others, notably Healy and Craig Venter, disagreed. At the time, pro-patent forces won out—Watson resigned and Venter went on to establish Celera Genetics and make major contributions to the human genome sequence (all the while filing many patents on his work).

20 years later the debate continues, as evidenced by the recent Myriad Genetics court case. Myriad is being sued by a number of different medical groups, scientists, and patients who believe that Myriad’s patents are impeding genetic research. Their core argument mirrors Watson’s: Genes are a naturally existing product, and therefore not patentable. Watson has filed a brief for the case which outlines his role in the Human Genome Project and his position on gene patenting.

The James D. Watson Collection contains boxes of material related to Watson’s contributions to the HGP, including administrative files from his time as Director of the NCHGR, lectures on the project, and correspondence with many of the major scientists who were involved with shaping the direction of the project. Below are some examples from the collection.

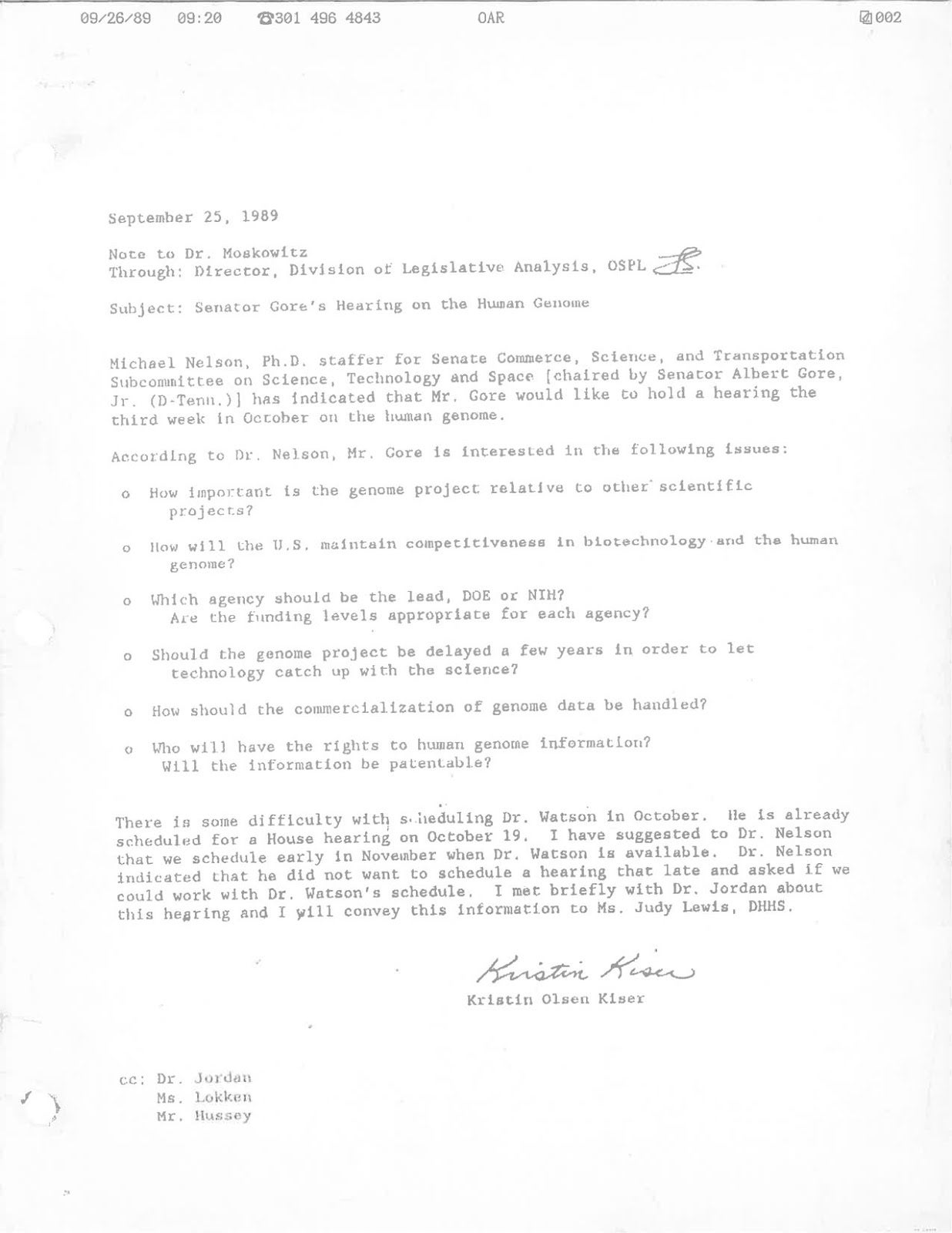

This memo is from then-Senator Al Gore regarding a hearing on the Human Genome Project. The document reveals that in 1989 Gore was already concerned about gene patenting.