In April of 1937, a botanist at the University of Arizona College of Agriculture named J. J. Thornber wrote to Carnegie Institution biologist A. F. Blakeslee for information about medical uses of Datura stramonium. This plant was the focus of Blakeslee’s research in the 1930s, and his scientific colleagues frequently wrote to him to discuss plant genetics or to request advice or seed samples. Thornber’s letter, however, fell into the category of medical rather than genetic research.

Thornber had heard of a “Chinese variety” of Datura, distinct from the D. stramonium that Blakeslee worked with, that was used to treat asthma. He wanted to find out if D. stramonium was equally effective, and asked if Blakeslee could send him some D. stramonium seeds so that he could try it out himself. “I may say,” he added, “that I have a patient who is perfectly willing to make the experiment if I can grow the material.”1

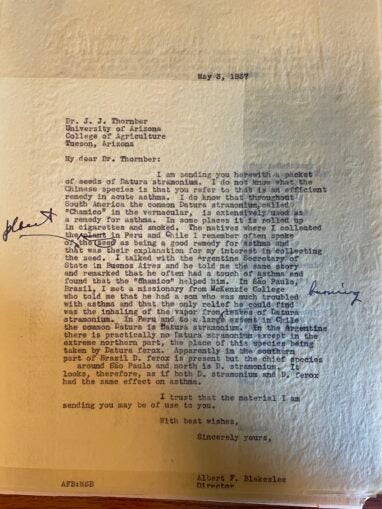

In some places it is rolled up in cigarettes and smoked. The natives where I collected the seed in Peru and Chile…often spoke of the plant as being a good remedy for asthma and that was their explanation for my interest in collecting the seed. I talked with the Argentine Secretary of State in Buenos Aires and he told me the same story and remarked that he often had a touch of asthma and found that the ‘chamico’ helped him. In São Paulo, Brazil, I met a missionary from McKenzie college who told me that he had a son who was much troubled with asthma and that the only relief he could find was the inhaling of the vapor from burning leaves of Datura stramonium. In Peru and to a large extent in Chile the common Datura is Datura stramonium. In [Argentina] there is practically no Datura stramonium except in the northern part, the place of this species being taken by Datura ferox. Apparently in the southern part of Brazil D. ferox is present but the chief species around São Paulo and north is D. stramonium. It looks, therefore, as if both D. stramonium and D. ferox have the same effect on asthma.2

The information in Blakeslee’s letter to Thornber highlights multiple connections between the history of science, the history of medicine, and the wide world beyond the lab in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the West, the idea of inhaling the smoke created by burning medicinal plants in order to relieve respiratory problems can be traced back into antiquity. The treatment’s popularity waxed and waned over the centuries before seeing a surge in the western world in the 1800s as smoking in general — typically tobacco, but also cannabis and opium — was adopted by more and more people from all walks of life. (Europeans had known about and used tobacco since the earliest days of colonial settlement in the Americas, but it was in the 1800s that it truly became a mass product.) Asthma medication was widespread through the early 1900s, in the form of cigarettes and as powders that the patient could burn in order to inhale the smoke.3

The use of Datura stramonium for this purpose has its own distinct history. Although both American and Asian origins have been ascribed to Datura, the most recent research indicates that Datura is native to the Americas. It is now found all over the world. British colonizers in India around 1800 learned that people there smoked Datura ferox, sometimes mixed with tobacco, to treat asthma. (That tobacco, an American plant, had reached India and was used there in combination with the equally well-traveled Datura points to the extent of global biological exchange — and human creativity — over the centuries). British doctors and asthma patients soon turned to the closely-related and more readily available Datura species growing along their own roadsides, Datura stramonium. D. stramonium became one of the most common ingredients in various powders, medicinal cigarettes and other preparations for treating asthma.4 Blakeslee’s comments about Datura’s widespread use in South America suggest that people there had independently discovered its usefulness for respiratory problems. The Spanish name for Datura that Blakeslee mentioned, ‘chamico,’ derives from a Quechua word, chamiku.5

At the time that Thornber wrote to Blakeslee, there were already significant changes underway in the treatment of asthma. Better understanding of the disease had led to more effective medications. Some of them used active ingredients derived from D. stramonium, such as atropine, but there were many others as well. In general, these new medications worked better and had fewer side effects than smoking Datura. Ironically, starting in the 1940s, tobacco companies tried marketing stramonium cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool, since stramonium cigarettes had a number of moderately unpleasant side effects — dry mouth was the primary one — and, so the thinking went, might create unpleasant associations with smoking that would help people quit. Herbal cigarettes containing “stramonium, eucalyptus and other plant extracts” continued to be marketed as an asthma treatment, although on a far smaller scale, into the 1970s.6

The letters that Blakeslee and Thornber exchanged in 1937 can be found in the Carnegie Institution of Washington Collection at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Library and Archives.

Notes

[1] CIW Box 9, Folder: Carnegie Institution of Washington, Dept. of Genetics, Blakeslee A. F., 1937, J. J. Thornber, botanist at University of Arizona College of Agriculture, to Blakeslee, April 20, 1937. [2] CIW Box 9, Folder: Carnegie Institution of Washington, Dept. of Genetics, Blakeslee A. F., 1937, Blakeslee to Thornber, May 3, 1937. [3] Mark Jackson, “‘Divine Stramonium’: The Rise and Fall of Smoking for Asthma,” Medical History 54, 2 (2010): 173-177, 181-183. [4] Jackson, “Divine Stramonium,” 177-181. [5] Real Academia Española, Diccionario de la lengua española, 2021. [6] Jackson, “Divine Stramonium,” 190-192.