Zinder to Weiner, July 21, 1976. CSHL Archives.

We can see this in connection with recombinant DNA research in the 1970s. Documents in the CSHL archives show how some scientists in Europe worried that the Americans were being dishonest in their attempts to limit recombinant DNA research until the risks were fully assessed.

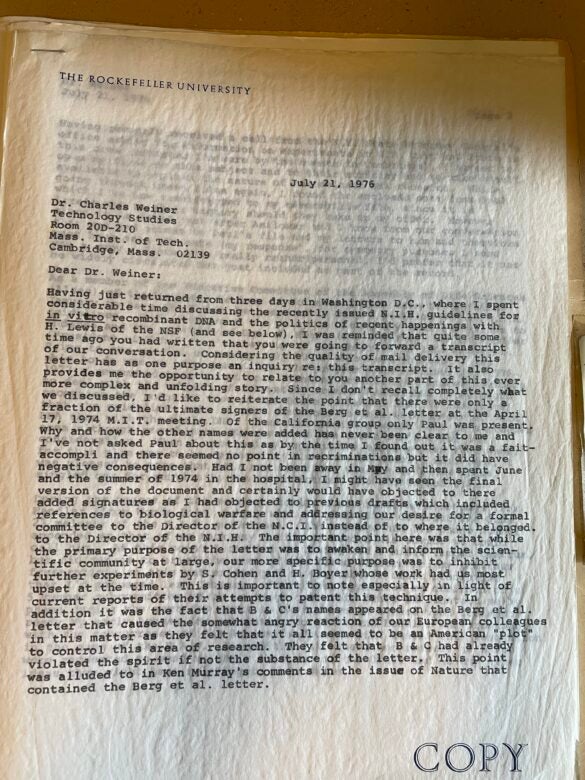

In July of 1976, microbiologist Norton Zinder wrote to historian of science Charles Weiner of MIT, who was putting together a history of recombinant DNA. Zinder wanted to let Weiner know more about the famous “Berg letter,” an open letter by Paul Berg and ten other scientists which was published in Science in July of 1974.1 In this letter they called for a moratorium on further experiments until the risks were better known. What Zinder wanted to tell Weiner was only a few of those whose names were attached to the letter had actually been at the meeting that produced the text. “How the other names were added has never been clear to me,” Zinder wrote, “and I’ve not asked Paul about this as by the time I found out it was a fait-accompli and there seemed no point in recriminations but it did have negative consequences.” Two of these names that were later added were those of Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer, who are often credited with the invention of recombinant DNA methods.

“The important point here,” Zinder told Weiner, “was that while the primary purpose of the letter was to awaken and inform the scientific community at large, our more specific purpose was to inhibit further experiments by S. Cohen and H. Boyer, whose work had us most upset at the time. This is important to note especially, in light of current reports of their attempts to patent this technique.” Cohen and Boyer, in other words, were signatories to a letter that was in part designed to prevent them from continuing with a line of research they themselves had opened up and which they evidently wanted to pursue.

“In addition,” Zinder continued, “it was the fact that B & C’s names appeared on the Berg et al. letter that caused the somewhat angry reaction of our European colleagues…as they felt that it all seemed to be an American “plot” to control this area of research. They felt that B & C had already violated the spirit if not the substance of the letter.”2 Zinder noted that a colleague in Edinburgh, Ken Murray, had referred to this in comments published in Nature. In his comments, Murray noted that the “NAS [National Academy of Science] embargo covers two types of experiment (which have already been accomplished by some of the signatories of the statement),” a reference to Boyer and Cohen.3 To the Europeans, it looked like the Americans were calling for a general moratorium on recombinant DNA research while at the same time looking the other way when researchers in the United States violated the very rules they were calling for and continued developing the technique. The financial as well as scientific advantages at stake were suggested by Boyer and Cohen’s efforts to patent the technique.

The European scientists in this case were not wrong to be concerned that their colleagues in the United States might edge ahead in the race to develop and exploit this new technology. Scientific reputations and a lot of money were at stake. And it made a difference where and under what circumstances new discoveries were made. Within a few years of Zinder’s letter, differences between the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe in terms of patent law would play a significant role in the international development of the recombinant DNA-based biotechnology industry.

Notes

1 Paul Berg et al., “Potential Biohazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules,” Science 185, 4148 (July 26, 1974): 303.

2 Norton Zinder Collection, Series: Rockefeller, Box 26, Folder: C. Weiner MIT, History of DNA REC, Zinder to Weiner, July 21, 1976.

3 Ken Murray, “Alternative Experiments?” Nature 250 (July 26, 1974): 279.