The CSHL Library and Archives has been awarded the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) Basic Processing Grant, which will allow us to catalog and make available over a dozen collections that we currently house in the archives. This will be the first in a series of posts which will highlight the various collections included in the grant and provide insight into what it actually means to “process” the materials held in our archive.

Initial Report on the Norton Zinder Collection

The Norton Zinder Collection is one of the first collections being worked on as part of the NHPRC Basic Processing grant. The Zinder papers were selected for inclusion in the project because he is an active, prominent scientist in the field of molecular biology, as well as a long-time member of the CSHL community as a former member of the Lab’s board. As part of the Basic Processing project, our goal is to provide a global audience with access to formerly “hidden” materials. We will accomplish this by applying the “basic processing” approaches suggested by Greene and Meissner in “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing” (pdf) (American Archivist, Vol 68 (2005) p 208-263), which at a bare minimum requires the creation of a catalog record and a brief overview the collection’s contents.

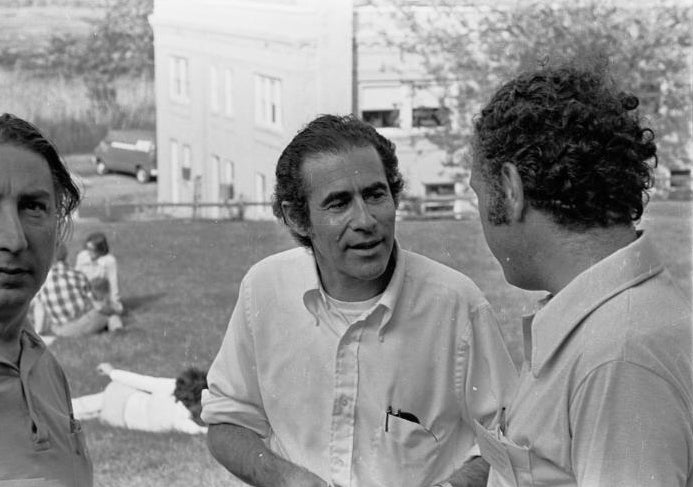

Norton Zinder, a New Yorker, received his A.B. degree from Columbia University in 1947 and went on to the University of Wisconsin where he received a Ph.D. in 1952. He returned to New York in 1952 to Rockefeller University (then known as The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research) as an assistant. At Rockefeller, he was appointed an associate in 1955, associate professor in 1958 and professor in 1964, all the while conducting significant research in molecular biology. With that brief introduction, the processing of the contents of Norton Zinder’s Rockefeller University office began.

First, the numerous monographs which were included in the Zinder Collection were inventoried. The 335 books included scientific textbooks, treatises, and collections of research papers presented at various conferences. The volumes ranged in publication dates from 1913 to 2002; the authors include a pantheon of twentieth-century geneticist and molecular biologist. His name was neatly handwritten or stamped on the inside cover of his undergraduate textbooks.

Next, the 84 document cases of reprints (republications of scientific articles) were inventoried. The papers provide insight into what Professor Zinder found significant for his professional edification. The reprints were kept in a series of meticulously arranged boxes, which were sorted alphabetically the author’s last name. When a paper included multiple authors, Zinder underlined the name under which the reprint would be filed; this arrangement schema was maintained during processing. Over 700 authors are represented in the collection, which are dated from 1931 to 1998. Most are printed in English, although there are a smattering in German and French, as well as an interesting collection of Japanese papers on radiation.

The next report will continue this exploration of the contents of Norton Zinder’s office as was given to CSHL. The lab notebooks and thick black binders await description and a place in the spectrum of this collection.

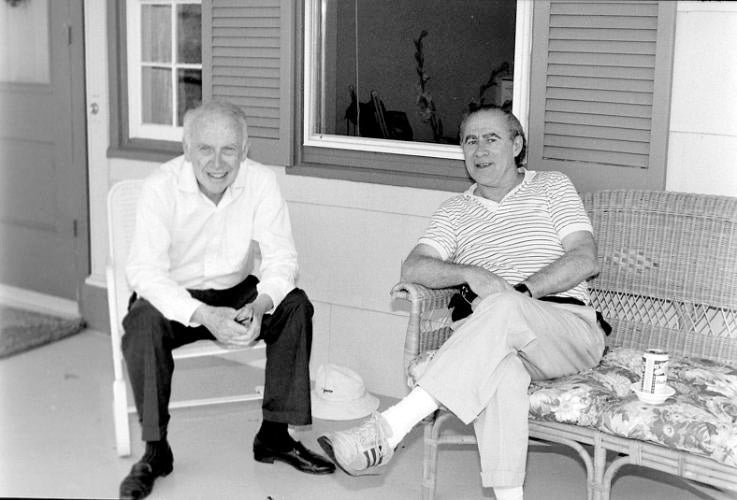

Getting to know Norton Zinder

For the past few months, I have had the privilege of working on the Norton Zinder Collection, which reflects over fifty years of his exciting and fulfilling scientific career. One of the many strengths of this collection is how clearly it illustrates his role as a powerful force that shaped national scientific policy from the 1960s to the 2000s. It raises the question of whether the scientific community truly understands the value of someone with Zinder’s ability to write and testify before Congress in a coherent, effective manner on the difficult scientific concepts that gnaw at society’s deepest fears and anxieties.

The scientific method

Zinder was an active participant in five dynamic decades of biological science, emerging from the confines of the laboratory to national and international arenas addressing political and moral issues such as recombinant DNA research guidelines, the demilitarization of chemical weapons, abortion, scientific misconduct, and the Human Genome Project. Notwithstanding the demanding travel and Congressional testimony schedule, he maintained an active role in the transition of Rockefeller Institute into Rockefeller University, with all the mundane administrative issues thereto. At Rockefeller, he mentored numerous students while conducting research in his lab. All the while he also engaged the public by speaking with school teachers and even corresponding with an 8th grader about their science project.

Included in the collection are more than 60 lab notebooks dating from 1953 to 2000. This compilation of data represents his bacteriophage research performed at Rockefeller University, where Zinder started as an Associate in 1953. He achieved the rank of Professor in 1964 and John D. Rockefeller Professor in 1977. Additionally, he served Rockefeller University as the Head of the Laboratory of Genetics until he retired in 1998.

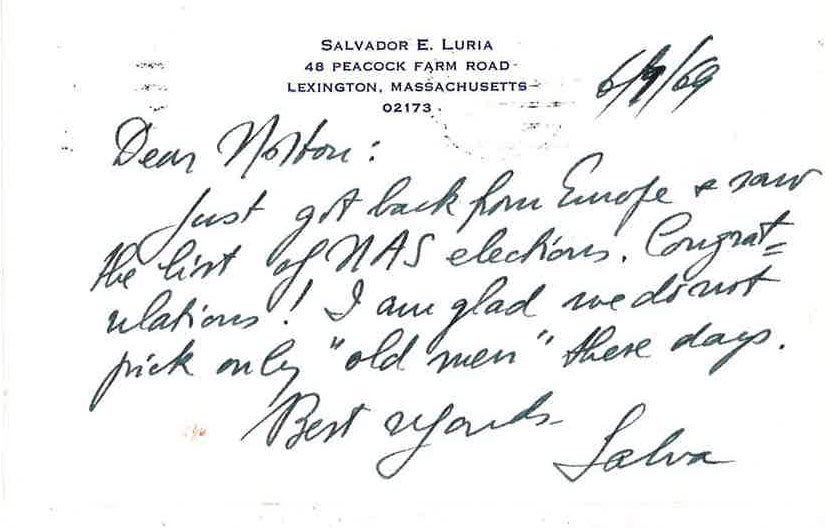

National service

A significant part of the Zinder Collection relates to his five decades of National Academy of Science (NAS) activities. He was elected to the NAS in 1966, early in his career, and actively participated in several capacities. During the 1960s he was involved in the reorganization of NAS. In the 1970s he testified before the US Senate regarding policy issues on the use of recombinant DNA. He also appeared before the US House of Representatives Committee on Human Rights and began his extensive committee work on the Disposal of Chemical Weapon Stockpiles. During the 1980s Zinder continued to research, organize and testify on behalf of the National Research Council (NRC) established under NAS auspices. The 1990s brought his active comment on the policies and procedures of the Human Genome Project. During this period, Zinder also wrestled with the unpleasant issue of scientific research misconduct and the ramifications on academic funding. In this new century, Zinder continued his nomination of NAS members, Foreign Associate members, and manuscript reviews as well as giving general advice and comments to scientific leaders and policymakers.

Science vs National secrets

In addition to his meticulous expense records for carfare and modest meals incurred in the trips to Washington D.C., there is included an interesting cache of 1970-73 correspondence regarding the issue of members of the National Academy of Science and its undertaking of classified work for the United States government, which at the time was in the throes of the Vietnam conflict. These research projects would not be shared or made available to other NAS members in alleged contravention of the principal purposes of the NAS, under its charter, to provide technical advice to the government by drawing upon the entire national scientific community by way of research funding. Some member scientists found a moral dilemma in the situation where “secret” work was performed by NAS members under NAS/NRC letterhead and forwarded to the Department of Defense without disclosure to all NAS members. A flurry of correspondence, meetings, and draft resolutions resulted as the NAS tried to reconcile the needs of the nation with their scientific mandate of information exchange. Zinder’s articulate writing, testifying, and commenting on scientific issues reflect a profound respect for the defense of the country that provided refuge to his immigrant parents, as well as the need for a free flow of scientific information.