Harold Schmeck, one of the science journalists involved in covering this news as it moved from the scientific community to the public at large, has argued that how this story broke had a significant effect on how it was perceived. The potential dangers posed by recombinant DNA had been discussed in the scientific community for some time before the news reached the press — most journalists missed the communications in journals like Science, where much of the early debate had taken place. Several different news outlets then caught wind of the story nearly at once and raced to be the first to cover it. The effect of this sudden explosive coverage was to give the impression that “the cataclysm was at hand,” which was not the intention. Part of the seeming urgency of the issue, in other words, was an artifact of how it got from the lab to the pages of The New York Times, the Washington Post — or the National Enquirer.1 But this did not make public concern, or the concern of many members of the scientific community, any less real. For many laypeople, tinkering with the “essence” of living things was a frightening idea. In addition to fear of potentially dangerous life forms, many people expressed fear and suspicion of scientists themselves — that researchers either didn’t understand or didn’t care about the potential dangers to human beings and the environment. Scientists, for their part, often expressed frustration at what they saw as journalistic sensationalism and sloppy or uninformed argumentation offered by opponents of genetic engineering. This was especially true by the later 1970s, when the vast majority of the scientists working with those methods had agreed that the risks were minimal. Nevertheless, the debate continued over whether and to what extent this type of research should be regulated and whether scientists should be subject to outside controls on what types of research they could do. All of this suggests that the development of recombinant DNA technology itself was what triggered a lot of these problems and issues. But was it?

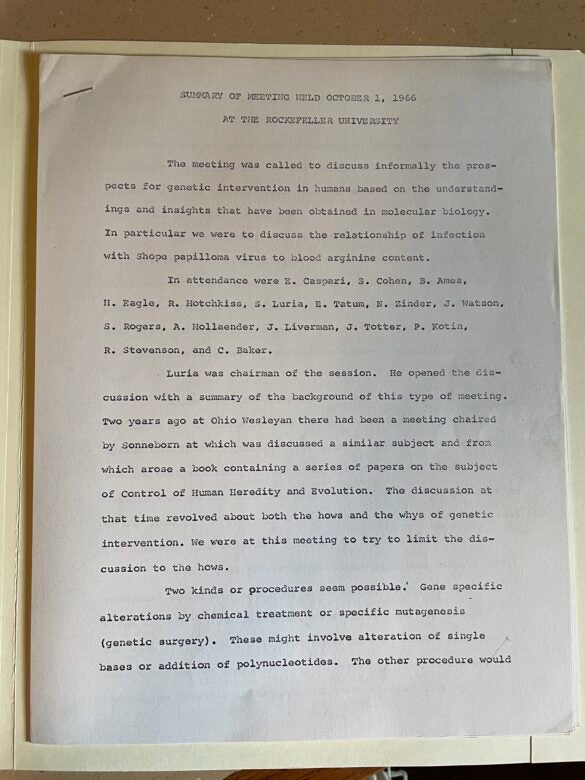

In October of 1966, years before biologists in California discovered how to splice genes, a group of scientists met privately at Rockefeller University “to discuss informally the prospects for genetic intervention in humans based on the understandings and insights that have been obtained in molecular biology.” 2 Even before rDNA, in other words, the progress that had already been made in the field had moved genetic engineering in people out of the realm of science fiction.

In fact, there had been a meeting two years before at Ohio Wesleyan University about the same topic and involving some of the same people. Essays from that meeting had been combined into a book, The Control of Human Heredity and Evolution, ed. T.M. Sonneborne (New York: Macmillan, 1965). The Ohio Wesleyan meeting had ranged widely over both the science of potential human genetic engineering as well as the psychology or sociology, and participants expressed a variety of perspectives — Aldous Huxley’s dystopian science fiction novel, Brave New World, was referenced repeatedly.

This meeting at Rockefeller in 1966 was intended to focus more narrowly on how rather than whether or in what context genetic manipulation of humans might be carried out. (Our source for the discussion at this meeting is a summary based on notes taken by Norton Zinder; see note 1 below.) Of particular interest was something that researchers had noticed in people who had been working with the Shope papilloma virus, a DNA virus that infects rabbits and causes horn-shaped skin tumors. Two observations were key here. The first was that when the virus infected epithelial cells (cells that form the covering of all body surfaces and line body cavities and hollow organs like the digestive tract) an enzyme, a type of arginase, was produced. Arginase catalyzes a reaction that turns arginine (an amino acid) and water into ornithine and urea. The second was that lab workers exposed to this virus “have no obvious clinical manifestations of disease” but nevertheless “fall into a group having low blood arginine content when compared with an unexposed population.” The implication was that the virus was causing the cells of infected individuals to produce this arginase, which was breaking down the arginine in their bodies. Was this arginase being produced by viral DNA? It was difficult to determine, but “a comparison of the viral-induced enzyme with the the enzyme produced in liver showed it to have a different molecular weight and different ionic requirements.” In other words, it was a slightly different sort of arginase than that otherwise produced by the host. In addition, both humans and rabbits infected with the virus produced anti-bodies to this unfamiliar enzyme. The evidence for how the arginase was produced was not conclusive, but the effects were long-term: “some of the individuals with low blood arginine contents had not worked with the virus for over twenty years.” This was evidence that “the effects of the initial exposure persist, one criterion for a successful genetic intervention.”3

All of this might seem very far removed from any genetically engineered ‘Brave New World.’ But the important point about the Shope papilloma virus example was that it seemed to suggest a mechanism for taking DNA from one organism and causing it to be expressed in another. According to Norton Zinder’s notes, “one has the impression that this is probably the way that genetic intervention might be accomplished in a reasonable time.”4

What was the next step — what was the best way to use this knowledge in terms of further research? One option was “a crash program with a federal agency as sponsor.” There is nothing in Zinder’s notes about this, but this sounded very similar to the NCI’s Special Virus Cancer Program, founded only a few years before to channel resources and research power into work on cancer-causing viruses. The ‘crash program’ was felt to be “premature,” however. Another idea was to put together a “small workshop meeting sponsored by a private agency such as The Rockefeller, in which chemists, virologists and geneticists, 30-40 people, would get together to discuss” the technical details.5

An important point to stress about this meeting was that the participants intended “to try to limit discussion to the hows” of this type of research, in contrast to the meeting at Ohio Wesleyan6. There was a sense among these researchers that they were on firmer ground when they limited their discussion to the science itself, rather than its broader implications. This point of view would re-emerge nearly a decade later in slightly different form at the Asilomar conference, where participants made a point of limiting their discussion of recombinant DNA research to the limitation of risk in a technical sense — that is, physical containment of research organisms and basic lab safety procedures.

But broader questions did creep in. There was “some discussion as to whether we should stimulate this kind of thing…The general conclusion seemed to be that if it is not done by us, others will do it and they won’t do it as well.” The question was raised as to whether it was really possible to “discuss the feasibility of such endeavors without discussing the desirability?” Some thought they could, others disagreed. One participant “pointed out that eugenic potential has been available for many years and has not been used.” If the mere availability of something didn’t necessary mean it would be used, then researchers were off the hook, in a sense, if they developed methods that could be used to genetically engineer people: the decision and responsibility for the implementation would lie elsewhere. Another replied that what they were talking about wasn’t the same thing as eugenics, arguing that “eugenics measures generally have negative elements which involve large social structures and are therefore resisted, while genetic intervention is mostly positive and on an individual basis and as such has qualities analogous to those which sell soap.”7 The difference in this case would seem to be between something like forced sterilization laws on the one hand, and on the other, individual gene therapy for an inherited genetic disorder.

How much of the discussion, if any, should they publicize? There was general agreement that “there be no publication of the discussion nor an official report.” They had too little concrete information, for one thing, and there was also the fear of creating a media circus: “this area is so highly charged that no matter how carefully everything is said, it gets overplayed and overinterpreted.”8

Why was this meeting significant? First of all, this discussion at Rockefeller in 1966 suggests that a lot of the themes and issues that we associate with the recombinant DNA debate in the 1970s were present earlier — whether research into genetic modification of organisms should be done, the question of whether scientists should limit their responsibility in this area to technical concerns, scientists’ fear that what they were doing could be misinterpreted and the possible dangers exaggerated. The meeting was kept private, and so neither the press nor the public knew that this type of conversation was happening. As noted above, science journalist Harold Schmeck described how the discussion over recombinant DNA “percolated” within the scientific community for a year or two before it reached the public. Norton Zinder’s notes about the 1966 meeting at Rockefeller, as well as the reference this meeting made to the conference at Ohio Wesleyan, show that that the percolating had been going on for some time — not about rDNA specifically, because those techniques were not developed until the early 70s, but certainly with regard to very basic concerns about the risks and potential rewards of genetic engineering.

Notes

1 Harold Schmeck, “The Recombinant DNA controversy: the right to know — and to worry,” in Raymond A. Zilinskas and Burke K. Zimmerman, eds., The Gene-Splicing Wars: Reflections on the Recombinant DNA Controversy, AAAS Issues in Science and Technology (New York: Macmillan, 1986), 94-96.

2 Norton Zinder Collection, Series: Rockefeller, Box 26, Folder: Unlabeled, “Summary of Meeting Held October 1, 1966 at the Rockefeller University,” 1.

3 “Summary of meeting,” 2-3; Wikipedia, “Arginine” and “Arginase.”

4 “Summary of meeting,” 7.

5 “Summary of meeting,” 8.

6 “Summary of meeting,” 1.

7 “Summary of meeting,” 8.

8 “Summary of meeting,” 8.