Dr. Matthew Meselson is a geneticist and molecular biologist known for being heavily involved in chemical and biological warfare research and anti-war activism. Many documents in the collection are in regard to events including World War Two, the Vietnam War, and other instances during the Cold War. The collection contains correspondence, laboratory files, photographs, and other materials related to Dr. Meselson’s work with chemical and biological warfare. Explore the digitized collection on the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s digital repository.

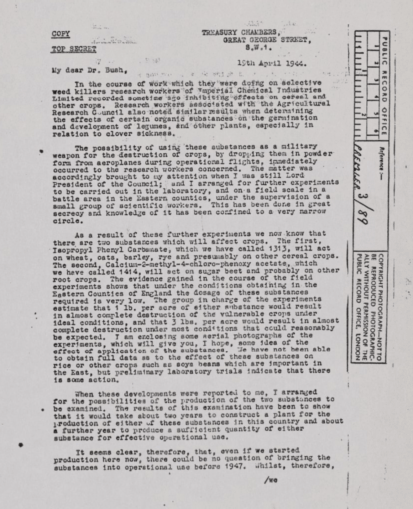

The oldest documents in the collection date back to 1944, during the midst of World War Two. The letters are between Dr. John Anderson and Dr. Vannevar Bush and detail the possible use of agricultural herbicides as a military mode of destruction of crops in enemy territories. Research on selective weed killers at Imperial Chemical Industries Limited led Dr. Anderson to come to the conclusion that there were two substances, 1313 and 1414, which would affect crops. He also identified which crops they would impact the strongest. Their research also determined that the amount of herbicide needed for complete destruction of crops in the area was extremely low, leading them to consider this method of warfare against the Japanese. The matter was also discussed with the Prime Minister of England, and it was estimated that only 1lb per acre of the substance, in ideal conditions, would result in near complete destruction of all crops in the area.

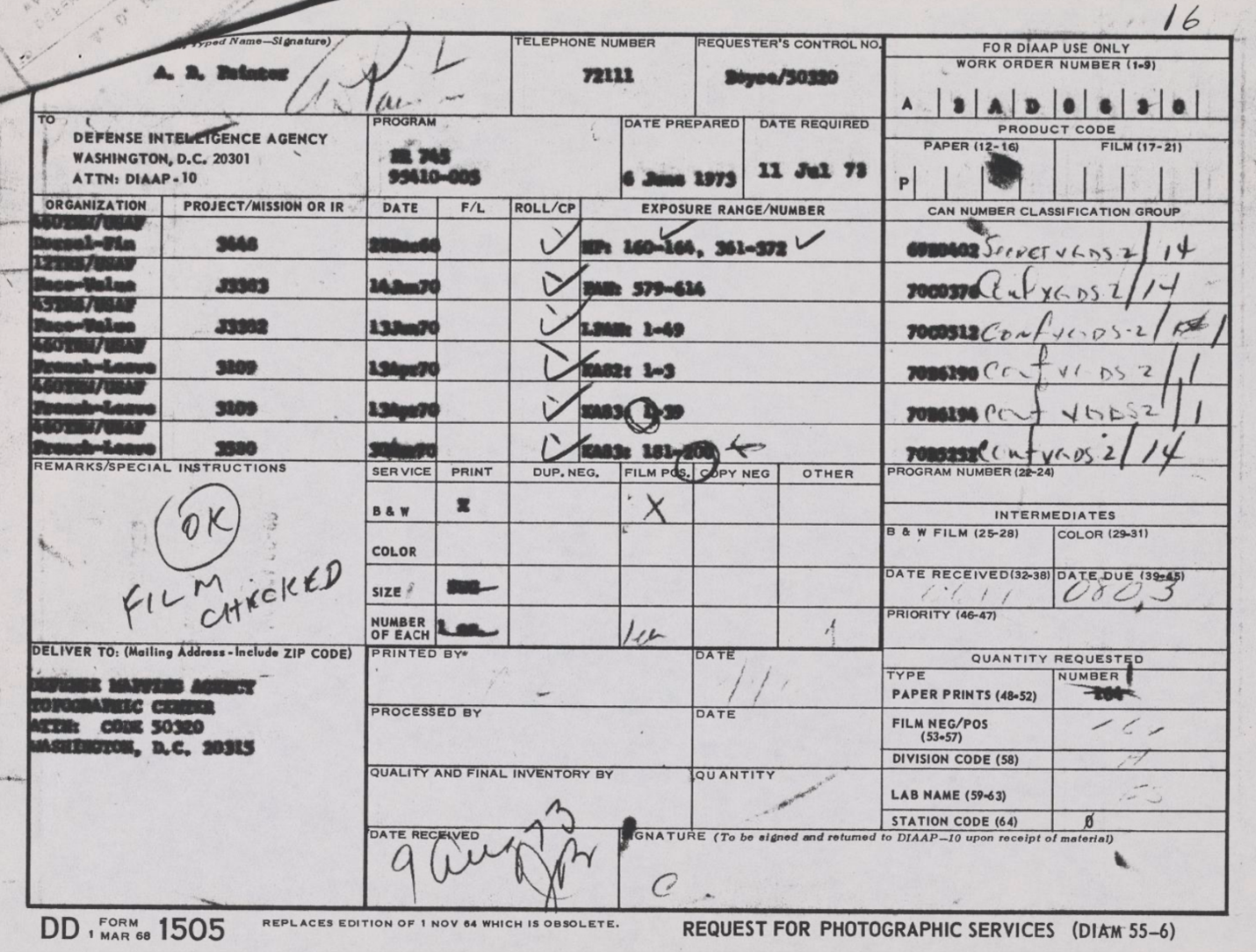

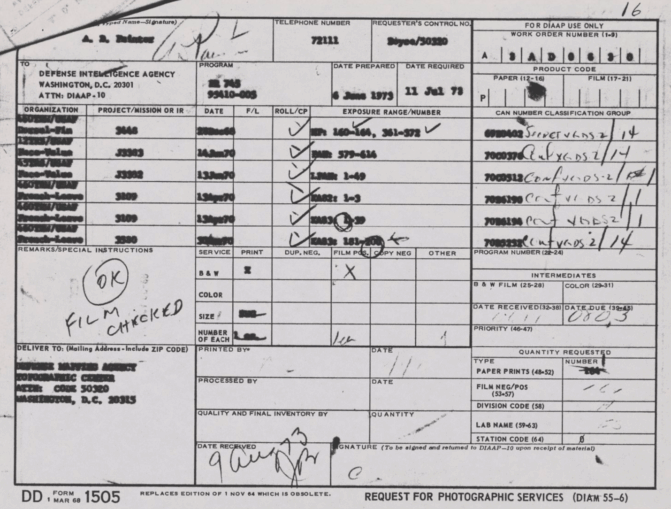

Although Dr. Meselson was still in school during the 1940’s, he had already begun investigating herbicide usage as a means of warfare during the height of the Vietnam War. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, little research was conducted regarding the impacts that pesticides and herbicides could have on human health despite the widespread usage of tactical herbicides in Operation Ranch Hand in 1962. In fact, one letter in the collection from July 1st, 1970, stated that there was “No new information on teratogenic effects of dioxin.” Dioxin was the main component of the infamous herbicides many are familiar with, such as Agent Orange.

In August and September of 1970, Dr. Meselson led a team in the Republic of Vietnam on behalf of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in a pilot study to investigate the impact chemical warfare has on human wellbeing. After obtaining conclusive proof of the detrimental effects of tactical herbicide dioxin on the health of those in Vietnam, President Richard Nixon ordered an “orderly yet rapid phaseout” of herbicide operations.

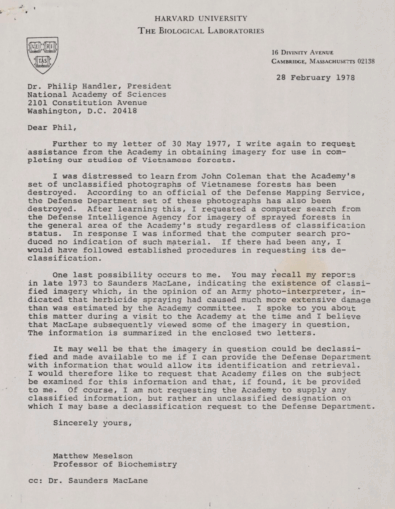

Even after the Vietnam War’s end in 1975, Dr. Meselson was still researching the effects of numerous herbicides in Vietnam. In his correspondence from 1978, Dr. Meselson searched for assistance in completing his study of Vietnamese forests; however, sets of unclassified photographs of Vietnamese forests had been destroyed.

Dr. Meselson’s collection also contains correspondence between U.S. government officials and other leading scientists regarding Soviet biological and chemical warfare subjects including alleged chemical weapon “Yellow Rain” and the Sverdlovsk bioweapons leak. Earlier correspondence regarding “Yellow Rain” refer to it as a “poison” and “lethal chemical weapon.” It was described as a poison gas from toxic mold, taking on the appearance of yellow clouds with granules falling from different heights upon Southeast Asian villages. Many Hmong people testified that they had developed symptoms including tremors, seizures, bleeding, and even death. In 1981, the U.S. accused the Soviet Union of using this “Yellow Rain” as a biological weapon.

However, as Dr. Meselson furthered his research, the testimonies of these people revealed many inconsistencies. While collecting this “Yellow Rain,” he found that many of these samples contained pollen—a substance that would likely serve no purpose as a means of biological warfare. Dr. Meselson then determined that “Yellow Rain” wasn’t a bioweapon, but in fact the mass defecation of Asian honeybees. More research regarding the phenomenon has led to more widespread agreement with Dr. Meselson’s findings, however the C.I.A. claimed that releasing this report in 2012, nearly thirty years after initial accusations, would be “preposterous.”

Whether “Yellow Rain” was truly a bioweapon or not, the answer remains blurry. On the other hand, the Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak held a much clearer answer. The earliest correspondence in the collection regarding it comes from 1980, a year after the outbreak occurred. Suspicions were raised about Sverdlovsk housing possible biological warfare research labs, and the fact that the outbreak occurred in that same city convinced many that the infection was a lab leak. The Soviet Union denied all accusations and merely labeled it as “meat contamination.”

In 1992, shortly after the Soviet Union’s collapse, President Boris N. Yeltsin of Russia finally admitted that the anthrax outbreak was a result of “military development” at the research facility in Sverdlovsk. Following this statement, Russia allowed U.S. scientists to investigate the outbreak. Dr. Meselson and others found that the infection was never foodborne, but in fact airborne. This finding led the team to conclude that an aerosol was responsible for the outbreak. The team’s findings were published in 1994 in Science.