You’ve heard the phrase, “Men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” If only it were so simple. The fact is that all of us are from Earth. Yet, there are clear physical and neurological differences between the sexes.

Women comprise half the world’s population. However, when it comes to health conditions that primarily affect women and girls, there’s a lot we still don’t know. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is working to fix that.

At CSHL, researchers study fundamental biology with an eye toward improving women’s health. Their explorations into cancer and neuroscience are helping us better understand how our minds and bodies can change over the course of a lifetime, from early development to menopause.

This new knowledge could lead to better treatments and prevention strategies for everything from breast cancer to diabetes. And it may help empower multiple generations of women from all walks of life.

Breast cancer prevention

Studies have shown that women who give birth before age 25 are less likely to develop breast cancer than women who never become pregnant and those who do so later in life. CSHL Associate Professor Camila dos Santos wants to know how this works. She suspects the answer might help us find new ways to prevent breast cancer.

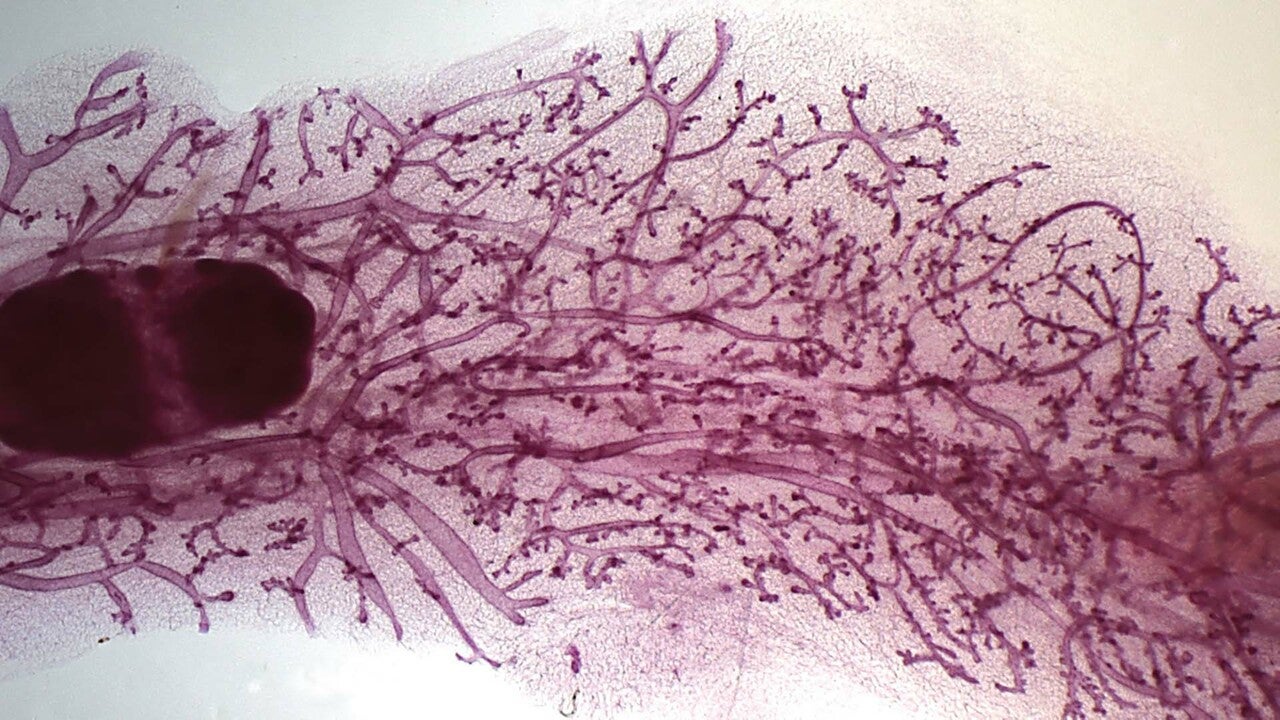

The dos Santos lab investigates how pregnancy changes breasts at the molecular level. Their hope is to identify specific changes within breast tissue that provide natural cancer protection. They’ve already uncovered a number of long-lasting changes that occur during pregnancy.

CSHL Associate Professor Camila dos Santos speaks about breast cancer prevention during a recent Cocktails & Chromosomes talk at Industry bar in Huntington, NY.

An early insight came when dos Santos was a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of former CSHL Professor Gregory Hannon. There, she discovered the genetic reprogramming that readies pregnant mice’s mammary tissue to reorganize in preparation for breastfeeding. This alters the ways certain genes are regulated, including many involved in cell growth.

It turns out that those changes leave a memory of a first pregnancy written into the breast cells themselves. “One of the things we’ve shown is that cells that have been exposed to pregnancy turn on processes that drive potentially cancerous cells to stall their growth,” dos Santos explains. “And eventually, they die.”

This led to another big discovery. In 2021, dos Santos and her team found that certain cancer-fighting immune cells called natural killer cells become much more prevalent in mice’s mammary tissue after pregnancy. The researchers say these natural-born killers could play a direct role in breast cancer prevention. They might actually patrol the tissue and destroy would-be tumors.

This discovery has also prompted the dos Santos lab to consider how immune cells’ interactions with the breasts might change at other times in women’s lives. They’re particularly interested in exploring changes brought about by menopause that might lessen the immune system’s innate ability to stop cells from becoming cancerous.

“All women during menopausal age are at risk of breast cancer,” dos Santos says. “What are the things that your body is erasing over time that puts it at risk? And can we bring them back to inhibit tumor development?”

Dos Santos notes that the effects of pregnancy on breast cancer risk are age-dependent. While risk is reduced significantly for women who give birth before the age of 25, pregnancy after 35 can increase breast cancer risk. The dos Santos team has begun investigating how, with age, breast cells respond differently to the hormones present during pregnancy. That work could help illuminate how breast cancer prevention strategies might shift over a woman’s lifespan.

CSHL Associate Professor Jessica Tollkuhn is also interested in hormones. You might say she’s one of the institution’s leading authorities on the topic. Tollkuhn focuses on the sex hormone estrogen, whose natural fluctuations—day to day and over a lifetime—have significant consequences for our physical and mental wellness.

Demystifying estrogen

The effects of estrogen are perhaps best understood in the context of breast cancer. The hormone can turn on genes that drive the growth of breast cancer cells. And women with certain types of breast cancer benefit from treatments that dampen estrogen’s growth-promoting signals.

Tollkuhn says that observing estrogen’s effects on breast cancer cells has enabled researchers to create more targeted therapies. “Understanding which genes are regulated by these hormone receptors has actually led to the development of better cancer therapeutics,” she explains.

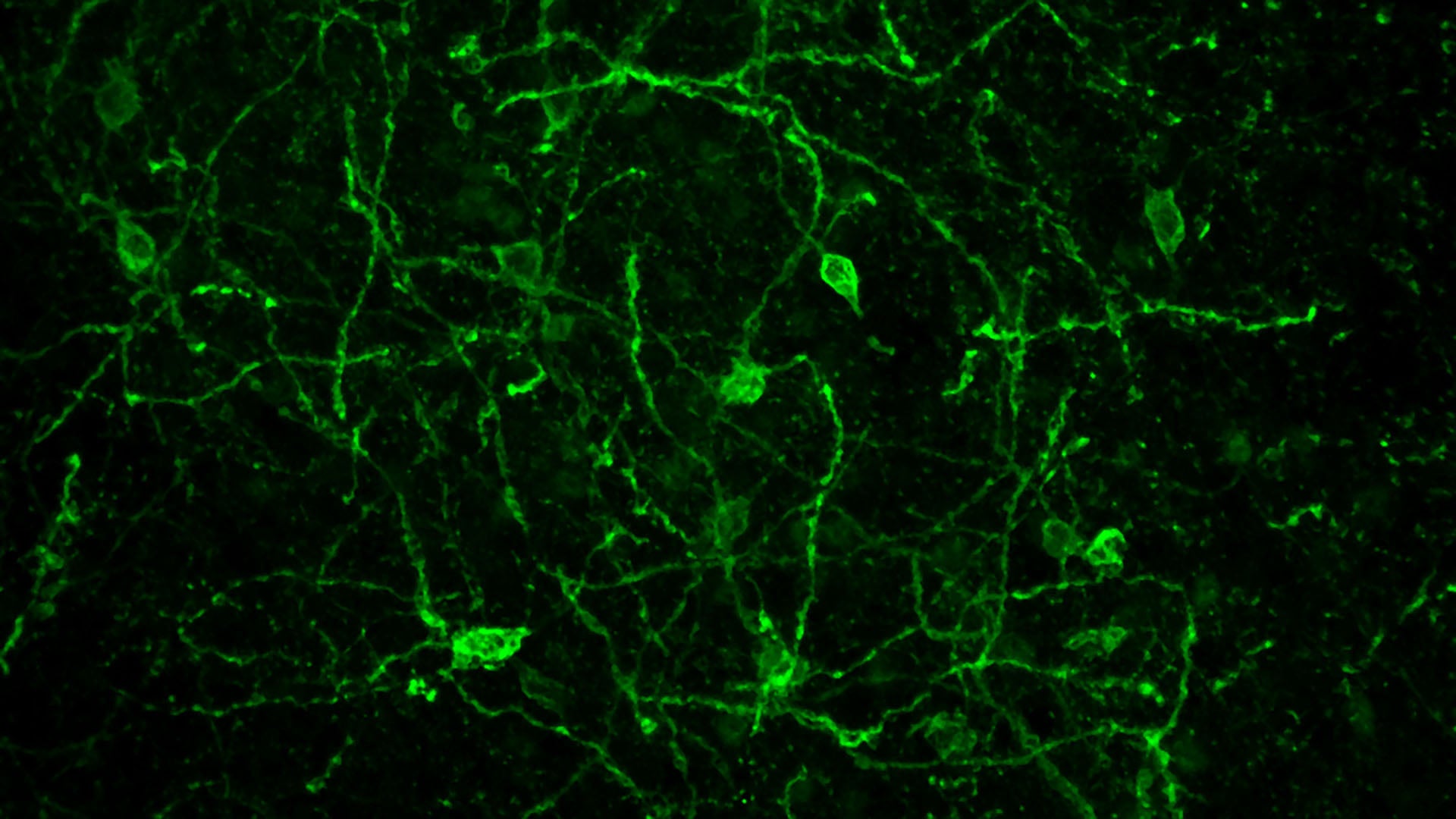

Of course, estrogen’s effects are not limited to cancer cells. The problem is that its impacts on healthy tissue aren’t yet well understood. Tollkuhn is particularly concerned with what happens when estrogen reaches the brain. How does it impact brain development after birth? What about later in life?

Estrogen is known to regulate mood and sleep patterns, protect against strokes, boost cognition, and help control body temperature. In fact, breast cancer treatments that rein in estrogen production can interfere with these functions. This can cause side effects like mood swings and hot flashes.

But until recently, no one really knew which genes estrogen targets in the brain. Tollkuhn’s work suggests that there are hundreds. In experiments with mice, she and her colleagues have found nearly 2,000 genome sites that interact with estrogen receptors in the brain. Her research has also revealed that sex hormones present in the developing brains of young animals influence their aggression levels and parenting abilities later in life.

With a long list of genes controlled by sex hormones, scientists can now explore how specific estrogen targets impact women’s health over the course of our lives. Take, for example, how estrogen levels decline during menopause. Hormone replacement therapies can reduce hot flashes and other symptoms triggered by this natural decline. However, for some women, raising the body’s estrogen levels may increase cancer risk.

Tollkuhn hopes her current work will empower researchers to develop therapies that mimic estrogen’s benefits without triggering undesirable side effects. “Now that we know what the genes are, can we figure out how to potentially activate those genes that are just in the neurons and not in the periphery?” she asks.

When neurons that naturally respond to estrogen are artificially activated in a mouse’s brain, the mouse moves. But when they’re not activated, the mouse stays relatively sedentary. Video: Krause/Ingraham lab

With collaborator Holly Ingraham at the University of California, San Francisco, Tollkuhn has already zeroed in on one gene in the brain whose diminishing activity after menopause may have an effect experienced by many women. That gene is Mc4r. The researchers have found it helps spur a motivation to move.

When estrogen levels decline, Mc4r activity wanes. This may help explain why women often become less active during menopause. Such lifestyle changes can make it harder to maintain a healthy weight and strong bones. So, keeping Mc4r turned up could counter these effects. And that could prevent common age-related conditions like obesity, diabetes, and the bone disease osteoporosis.

Brain-body and beyond

Menopause and pregnancy are just two women’s health issues coming into better focus as a result of CSHL research. There are also CSHL scientists studying uterine and ovarian cancers. Others have set their sights on the neuroscience of motherhood. How does the profound experience of raising a child affect our brains? And how do these neurological changes manifest physically?

Questions like these lie at the heart of CSHL’s brain-body initiative. It’s here that the work of cancer scientists like Camila dos Santos and neuroscientists like Jessica Tollkuhn intersects. The two study vastly different biological processes. Yet both recognize that their research has significant implications for women’s health. Their findings could lead to new breast cancer prevention strategies, hormone replacement therapies, and better overall patient experiences.

But more than that, their work stands to empower women of all ages and backgrounds. After all, knowledge is power. And thanks to CSHL research, our knowledge of women’s health grows stronger each day.

Written by: Jennifer Michalowski, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455