When you pick up a baby, you can’t help feeling happy. But where does this feeling come from? How does it influence future behavior? Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Associate Professor Stephen Shea has found that, when it comes to maternal care, social contact is its own reward.

“We know that, as human beings, it’s rewarding to touch another person,” he says. “But we know less about what drives this behavior, and how we perceive it to be rewarding.”

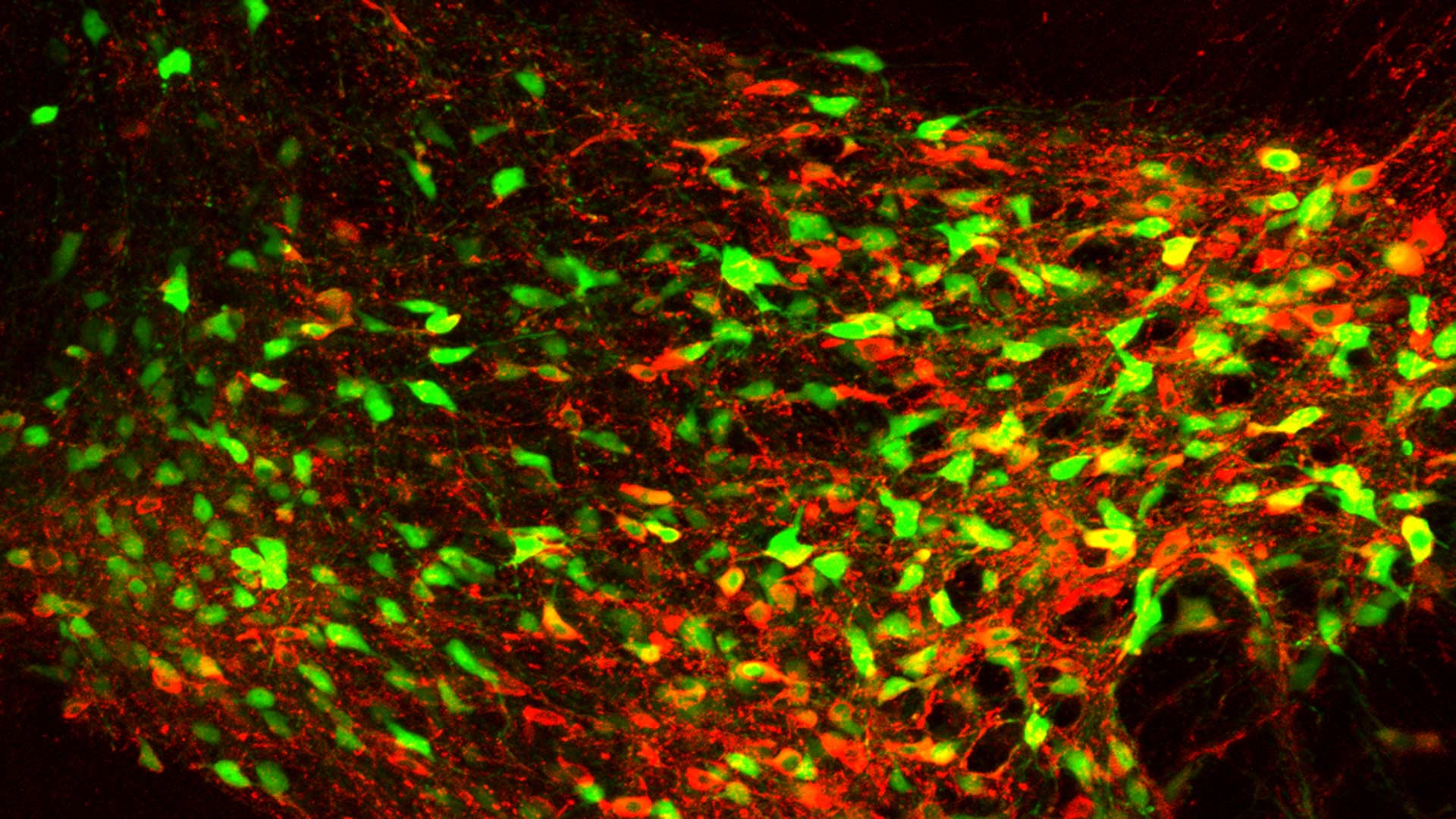

Shea and Postdoc Yunyao Xie traced maternal motivation in mice to a region of the brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA). They found that neurons in the VTA use dopamine to nurture maternal instincts through a process called reinforcement learning. When a mom picks up a crying child, their brain’s VTA neurons release dopamine. This creates an expectation of future rewards, driving them to pick the child up again the next time it cries. Shea says:

“It’s a very ancient mechanism in the brain that mice and humans and many other animals share. Dopamine is a complex molecule. It’s important for motion, reward, and motivation, but in this case, dopamine is actually instructing the behavior and reinforcing it.”

To observe reinforcement learning in action, Shea’s team built an enclosure with two chambers. They placed a mouse on one side and a pup on the other, behind one of two doors. They then played specific sounds to signal whether the pup was present and if it was behind door number one or two. Each time the mouse heard a sound and retrieved the pup, VTA neurons rewarded it with dopamine.

“Switching the neurons off in every trial prevented the mice from learning maternal behaviors,” Shea says. “But switching them off every other trial only slowed the learning down. By doing this, we could see that switching the neurons off didn’t immediately affect maternal behavior. Instead, it affected the behavior on future trials.”

Understanding how social contact is encouraged in mice gives researchers a clue about VTA neurons’ involvement in rewarding other behaviors. It also points to reinforcement learning’s role in how humans may perceive rewards.

Shea is now digging deeper into how VTA neurons work together and influence different types of social contact. He hopes to uncover the mental mechanisms behind human interactions. This may lead to a better understanding of how neurodevelopmental disorders affect people’s perceptions of social contact and reward.

“This is a very basic mechanism,” Shea says. “Understanding it is important both for helping people with conditions like autism and for answering fundamental questions about the brain that will inform future work.”

Written by: Nick Wurm, Communications Specialist | wurm@cshl.edu | 516-367-5940

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health, Charles and Marie Robertson Foundation, The Feil Foundation

Citation

Xie, Y., et al., “A dopaminergic reward prediction error signal shapes maternal behavior in mice”, Neuron, December 20, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.11.019

Principal Investigator

Stephen Shea

Professor

Ph.D., University of Chicago, 2004