Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Like pancreatic cancer, cancer of the ovaries is notorious for being discovered at a relatively late stage—after it has spread to other sites in the body. It is not called “the silent killer” for nothing. Fully two-thirds of women who are diagnosed find out at Stage 3 or later, once metastasis has begun. Fewer than 25% of such women survive 5 years—while the corresponding figure for those fortunate enough to be diagnosed at Stages 1 and 2, when the cancer is still localized, is between 70% and 90%.

Today, a team of researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory reports in the journal Genes & Development that they have arrived at “new insights into signaling events that underlie metastasis in ovarian cancer cells,” says Gaofeng Fan, Ph.D., postdoctoral investigator who conducted most of the experiments, in the laboratory of his mentor, CSHL Professor Nicholas K. Tonks.

“The statistics point to the urgent need to address advanced disease—metastasis—in ovarian cancer,” Fan says. “The problem is especially difficult because of a feature specific to this form of cancer: ovarian cells move around readily within the peritoneal cavity, via the peritoneal fluid, both under normal conditions, and also, unfortunately, when cancer is present. Thus, in addition to being able to colonize other sites in the body via blood vessels, ovarian cancer cells have another way of migrating. It’s very hard to render patients free of the disease via surgery due to this diffusion feature.”

Fan, Tonks and colleagues have found a previously undiscovered pathway through which ovarian cells can be transformed into cancer cells, one they think provides an excellent opportunity for targeting by new drugs, which, when combined with others now in development, may be able to stave off metastatic disease.

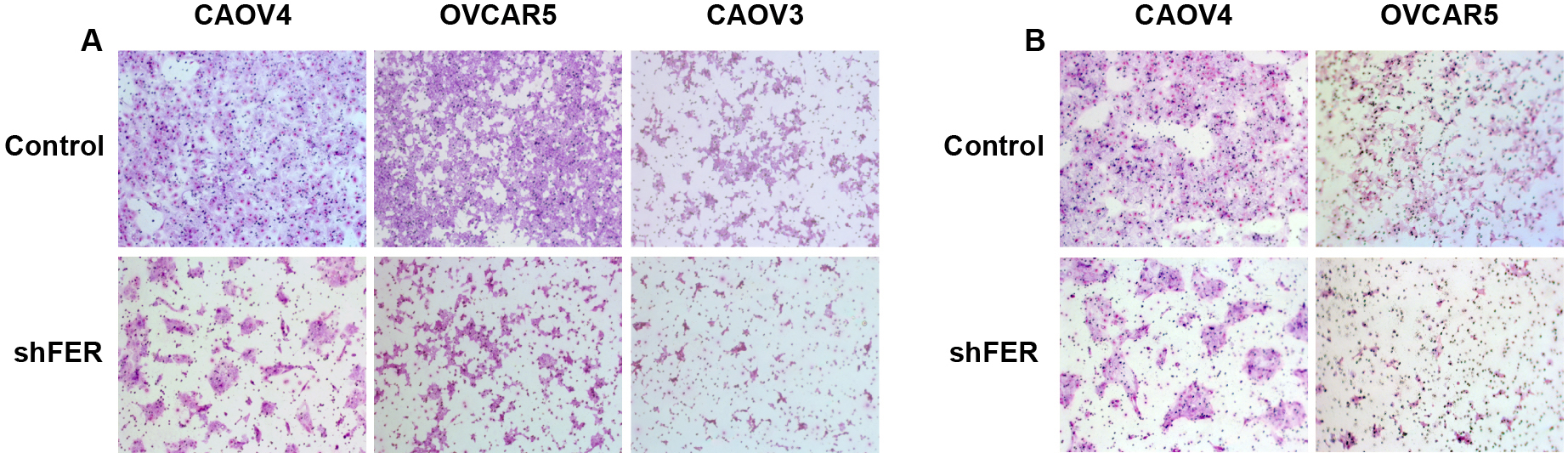

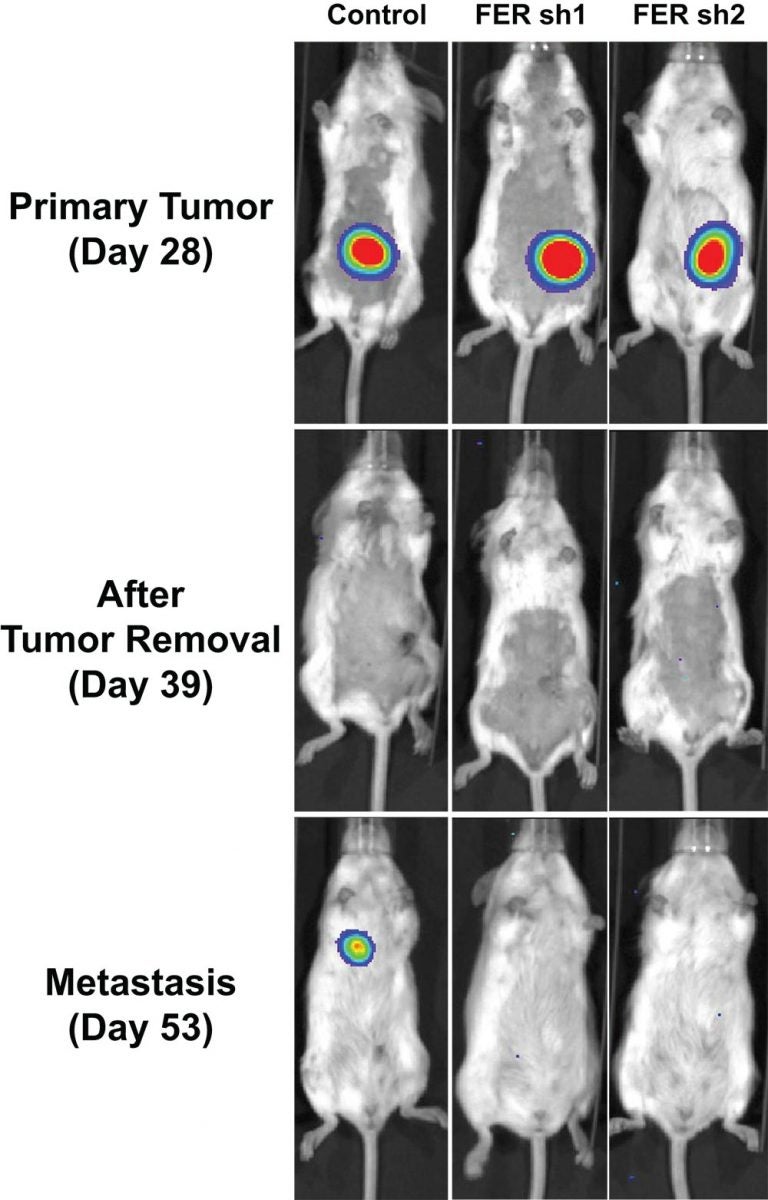

The newly uncovered pathway depends on activity of a protein called FER, a member of a family of proteins (called non-receptor tyrosine kinases) that add phosphate groups to other proteins. FER can be found floating in the cytoplasm of cells, and in a series of initial experiments, Fan and the team demonstrated that it is both “upregulated,” i.e., overproduced, in ovarian cancer cells, and, importantly, responsible for the elevated motility and invasiveness of such cells. This was observed in human ovarian cancer cells grown in culture, and then in mouse models of the disease.

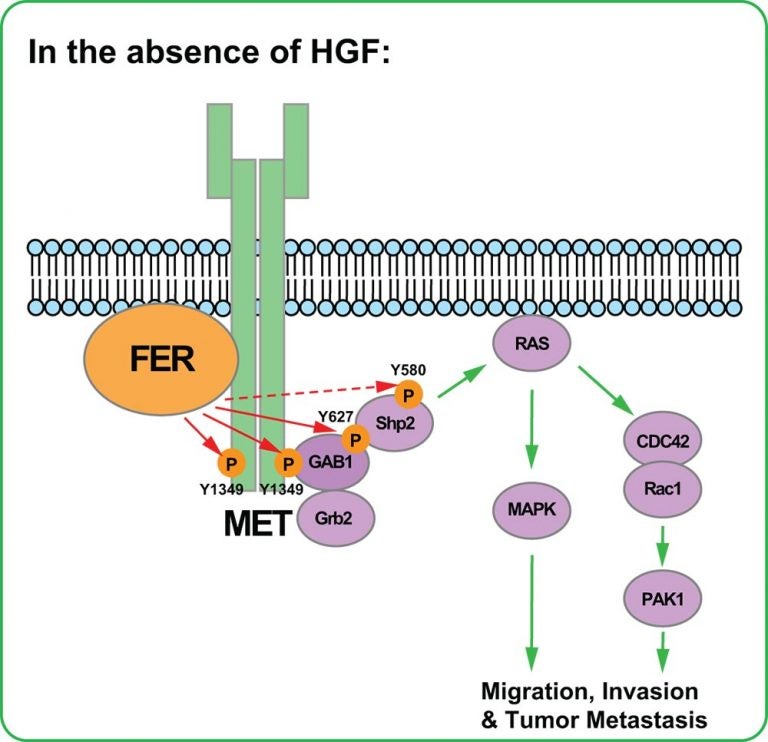

The key discovery made by the CSHL team is that FER is able to activate a receptor on the surface of ovarian cells “from below,” as it were—by interacting with a portion of the receptor that penetrates the cell membrane and plunges into the cytoplasm. That receptor is a well known target in ovarian cancer. Called MET, it is typically activated when a growth factor called HGF binds it at the cell surface. MET is overexpressed in up to 60% of ovarian tumors and its activation has been implicated in both cancer initiation and in advanced cancers with poor prognosis.

Unsurprisingly, then, MET is the target of a number of drug development efforts, which have in common the aim of blocking MET’s activation. So far, candidate MET inhibitors have had weak anti-tumor effects, when administered alone. “It seems ovarian cancer cells are finding other ways to activate pro-cancer signaling ‘downstream’ of MET,” Fan says.

The significance of Fan and Tonks’ research on FER is their discovery of how FER activates MET from below, i.e., in the absence of a growth factor docking at the receptor surface. They call this form of activation “non-ligand-dependent,” and in a complex series of biochemical and animal experiments, traced the pathway through which FER’s binding to MET inside the cell sets off a cascade of cell-signaling events, all directly connected in prior research with cancer initiation, including RAC1/PAK1 and SHP2-ERK.

By setting off these oncogenic cascades, FER, simply by adding a phosphate to the MET receptor, itself becomes a potentially attractive drug target. This is especially so since in animal models of ovarian cancer, Fan and the team demonstrated that FER’s suppression reduced cancer cell motility and sharply reduced metastasis.

“We showed FER was essential for ovarian cancer cell motility and invasiveness, both in vitro and in vivo,” Tonks says. “Considering that frequent amplification of MET accounts for resistance to therapies now in development and to poor prognosis, not only in ovarian cancer but in other cancers too, our findings pinpoint an important new signaling hub, involving the role of FER in MET activation. This may provide a novel strategy for therapeutic intervention, perhaps a drug to suppress FER being administered along with a MET inhibitor.”

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants CA53840 and GM55989, CIHR grant #219806, and the CSHL Cancer Centre Support Grant CA45508. Dr. Tonks is also grateful for support from the following foundations: The Gladowsky Breast Cancer Foundation, The Don Monti Memorial Research Foundation, Irving Hansen Foundation, West Islip Breast Cancer Coalition for Long Island, Glen Cove CARES, Find a Cure Today (FACT), Constance Silveri, Robertson Research Fund and the Masthead Cove Yacht Club Carol Marcincuk Fund.

Citation

“HGF-independent Regulation of MET and GAB1 by Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase FER Potentiates Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer” appears online in Genes & Development on July 11, 2016. The authors are: Gaofeng Fan, Siwei Zhang, Yan Gao, Peter A. Greer and Nicholas K. Tonks. The paper can be accessed at: http://genesdev.cshlp.org/

Principal Investigator

Nicholas Tonks

Professor

Caryl Boies Professor of Cancer Research

Cancer Center Associate Director of Shared Resources

Ph.D., University of Dundee, 1985