Gaining a deeper understanding of how the body works remains central to her research today—a somewhat unusual perspective for a breast cancer researcher. Rather than studying bodies broken by breast cancer and working backward, she is studying bodies with breasts that are still working properly.

“I see it as a car engine,” dos Santos says. “If you know how the engine works, then you know how it breaks, so you know what to fix.”

This approach stemmed from the work she did with blood cancers before coming to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. As a Masters and PhD student in Brazil, dos Santos’ work was informed by extensive pre-existing knowledge of how a cell develops from a basic stem cell into a cell specialized for a specific role in the blood.

When she arrived as a postdoc in the lab of Professor Greg Hannon, dos Santos was puzzled by the lack of a similar foundation in breast cancer research. She thought, “We know all of this about blood, why don’t we know this much about breasts?”

While working with Hannon, she also learned that an early pregnancy—that is, before the age of 25—decreases breast cancer risk by over 30 percent in women. Her work at CSHL so far has focused on revealing the changes that occur in the DNA within healthy breast cells, particularly those of the milk-producing mammary gland, after pregnancy.

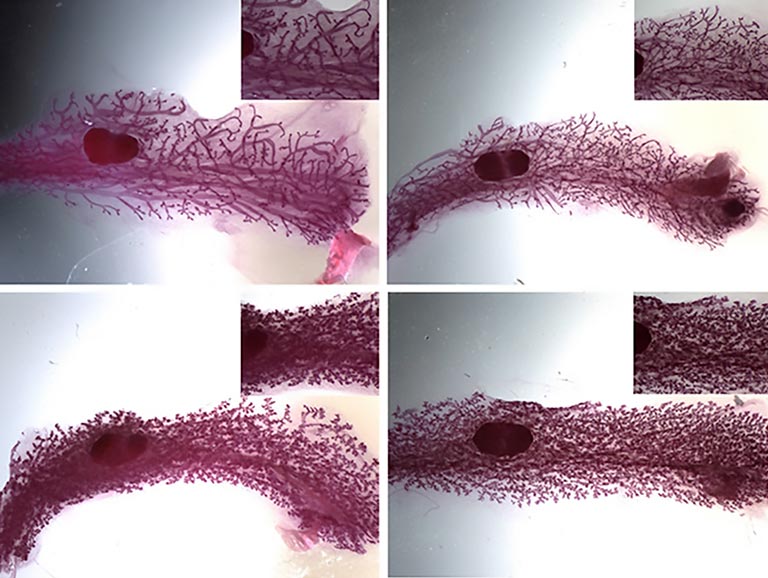

This work is still very much in progress, but an early study she worked on with Hannon shows that genetic signals present in mammary gland cells since the beginning of life get altered after a first pregnancy. Dos Santos hopes that by understanding these normal changes, she can pinpoint what goes awry when breast cells become cancerous.

Her data, so far, comes from mice. But her drive comes from the breast cancer survivors with whom Hannon helped her cultivate relationships as a postdoc. Amazed by both their strength and their knowledge about the disease, she meets with these women regularly to learn from them about what is really important in breast cancer research.

“They went through treatment, and they are cancer free—but they are not worry free,” dos Santos says, because breast cancer can come back. “They relive their fear about the cancer coming back with the purpose of saying, ‘You scientists who do this research, you have something much bigger than grants in your hands.’”