A novel surface marker helps scientists ‘fish out’ mammary gland stem cells

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Stem cells are different from all other cells in our body because they retain the remarkable genetic plasticity to self-renew indefinitely as well as develop into cell types with more specialized functions. However, this remarkable self-renewal capacity comes with a price, as stem cells can become seeds of cancer. Identifying genetic programs that maintain self-renewing capabilities therefore is a vital step in understanding the errors that derail a normal stem cell, sending it on a path to become a cancer stem cell.

Isolating cells from various other cell types is very much like fishing—you need a good “hook” that can recognize a specific protein marker on the surface of a cell, in order to pull that cell out. Until now, isolating pure mammary gland stem cells (MaSCs), which are important in mammary gland development as well as breast cancer formation, has posed a challenge. MaSCs are scarce and share common cell-surface markers with other cells. In a paper published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists in the laboratory of Professor Gregory Hannon at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) used a mouse model to identify a novel cell surface marker on MaSCs. Using that marker, the team was able to assemble a sample of MaSCs of unprecedented purity.

“We are describing a marker called Cd1d,” says CSHL research investigator Camila Dos Santos, Ph.D., the paper’s first author. The marker, also present at the surface of specialized immune cells, is expressed on the surface of a defined population of mammary cells in both mice and humans.

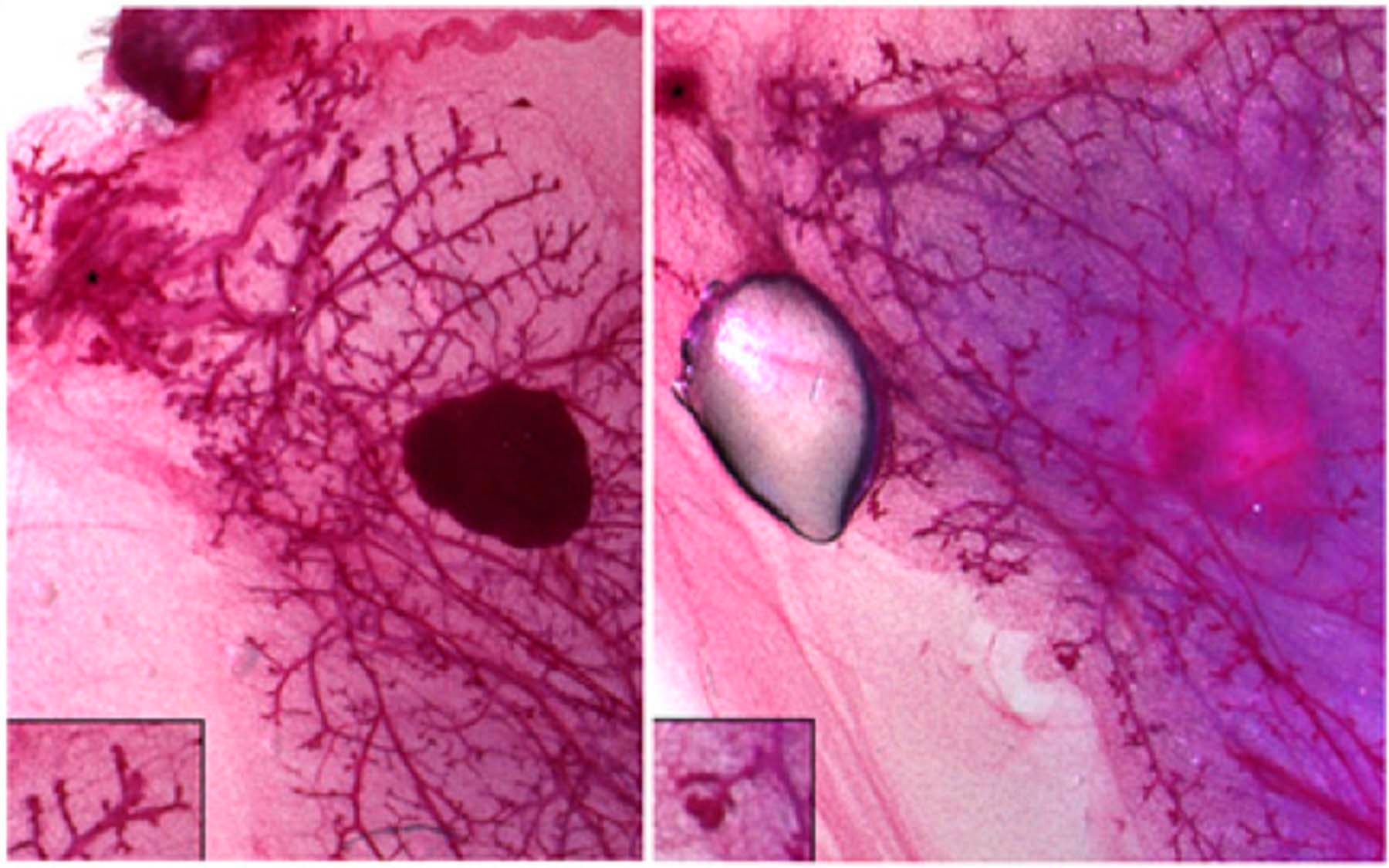

The team took advantage of the fact that MaSCs divide much slower than other cells. They utilized a mouse strain, which expresses a green fluorescent protein, or GFP, in a subtype of epithelial cells, including MaSCs. The trick is that this gene can be turned off by feeding mice a chemical called doxycycline. “The beauty of [this model] is that by stopping GFP expression, you can directly measure the number of cell divisions that have happened since GFP was turned off,” Dos Santos explains. “The cells that divide the least will carry GFP the longest and are the ones we characterized.”

Using this approach, Dos Santos and her colleagues were able to select stem cells in the mammary glands to examine their gene expression signature. They confirmed that a purification method that used Cd1d, in combination with other known markers, greatly enhanced purity compared to other methods, including those previously published.

“With this advancement, we are now able to profile normal and cancer stem cells at a very high degree of purity, and perhaps point out which genes should be investigated as the next breast cancer drug targets,” says Professor Hannon, who is also an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Written by: Yevgeniy Grigoryev, Guest Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This research was supported by NIH Grand Opportunity Award #1 RC2 CA148507 and P01 Award 2P01CA013106.

Citation

“Molecular hierarchy of mammary differentiation yields refined markers of mammary stem cells” appeared online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors are: Camila O. dos Santos, Clare Rebbeck, Elena Rozhkova, Amy Valentine, Abigail Samuels, Lolahon Kadiri, Pavel Osten, Elena Y. Harris, Phillip J. Urei, Andrew D. Smith, and Gregory J. Hannon.

The paper can be obtained at: DOI:10.1073/pnas.1303919110