What causes cancer? Science and medicine have been trying to answer this question for centuries. In the late 1800s, scientists observed that most tumors have an odd number of chromosomes. They thought this imbalance, called aneuploidy, may be a driving force in cancer development. Since then, technological advancements—and limitations—have pushed science in other directions. But now, thanks to experiments performed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, cancer research could come full circle.

Asad Lakhani guides a tour of his aneuploidy research at CSHL.

The experiments were led by Asad Lakhani, who recently graduated from the CSHL School of Biological Sciences, his doctoral advisor, Jason Sheltzer, and Vishruth Girish, a former CSHL research technician currently working on his M.D. and Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins University.

Now at Yale University, Sheltzer reflects on how cancer research has shifted focus over time. “Many early biologists thought aneuploidy caused cancer,” he says. “As the 20th century progressed, this view fell out of fashion. DNA sequencing found that tumors had mutations in individual genes, and cancer was attributed to these mutations. We still knew aneuploidy was present. It was just hard to study or manipulate, so it was treated like a bystander during cancer development.”

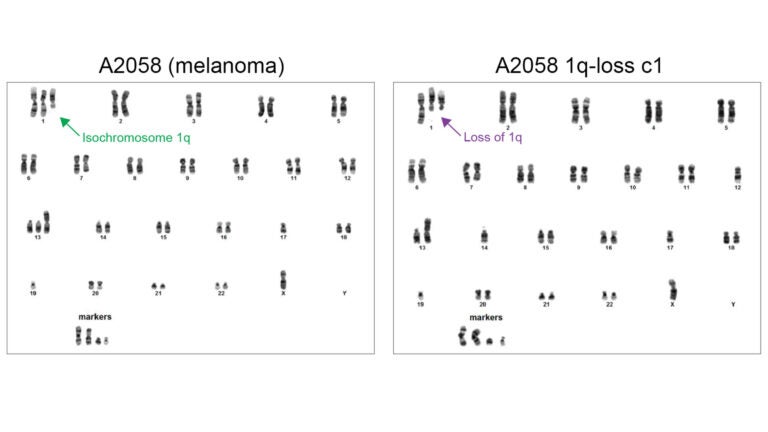

To settle once and for all whether aneuploidy was a mere bystander, the researchers came up with a new genome-editing technique on a scale never before achieved. Over the past decade, scientists have been able to delete individual genes or pieces of DNA using molecular “scissors” known as CRISPR. But with the new technique, called ReDACT (Restoring Disomy in Aneuploid cells using CRISPR Targeting), they can now slice off an entire arm of a chromosome. That could mean erasing over a thousand genes at once.

The team found that when aneuploidies are deleted from cancer cells, it cripples them. The malignant cells aren’t able to grow as fast and can no longer form tumors. “So, the aneuploidy in cancer cells isn’t just a bystander,” Sheltzer says. “It’s actually central for malignant growth, just like the 19th-century pathologists thought.”

Amazingly, ReDACT appears effective across a wide range of cancers, including breast, ovarian, and gastric cancer and melanoma. “We went at it in a cancer-agnostic manner,” explains Lakhani, now a postdoctoral researcher in CSHL Professor & HHMI Investigator Rob Martienssen’s lab. Lakhani says:

“We’ve made these tools publicly available. Hopefully, people will take these techniques and study their favorite chromosome, and will learn across all cancer types what the relative contribution of each aneuploidy is to tumor development. Perhaps that leads to more therapies.”

Lakhani thinks this work could open the door to personalized cancer treatments. “You can imagine if patients exhibit an extra copy of a chromosome in their tumors, perhaps they’re more likely to respond to therapies,” he says, “as opposed to patients who have the same tumor but not an extra copy.” If proven, this hypothesis could help guide the future of cancer therapeutics.

CSHL has a long legacy of groundbreaking biology. With time, Lakhani, Sheltzer, and Girish’s work might yet go down as another major breakthrough. Beyond the annals of science, their discovery may someday lead to better outcomes for countless cancer patients. Such an achievement would be truly historic.

Written by: Luis Sandoval, Communications Specialist | sandova@cshl.edu | 516-367-6826