Another proof of principle for TSUNAMI method in modeling spinal muscular atrophy and other splicing-related illnesses

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — A research team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has used a recently developed technology they call TSUNAMI to create the first animal model of the adult-onset version of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a devastating motor-neuron illness.

The same team, led by CSHL Professor Adrian R. Krainer, Ph.D., and including scientists from California-based Ionis Pharmaceuticals, as well as the University of Southern California and Stony Brook University, succeeded a year ago in using TSUNAMI to make a mouse model of the disease as it is manifest in children. In its most severe form, called Type I SMA, the disease is the leading genetic cause of childhood mortality. Half of infants with Type I SMA die before their second birthday.

Many SMA patients do reach adulthood, however, and on occasion people develop symptoms of the illness only after they have become adults. Hence the importance of the team’s success, reported online today in EMBO Molecular Medicine.

All patients with SMA, regardless of their age, have a non-functional version of a gene called SMN1, or are missing it entirely. The acronym “SMN” stands for “survival of motor neuron” and suggests why SMA is so serious. The SMN1 gene encodes a protein, called SMN, that motor neurons need in order to function. Humans have a backup copy of the gene, called SMN2, which produces the same protein, but in much lower amounts.

The body’s manufacture of the SMN protein from the SMN2 gene can limit the impact of SMA. How much a patient is helped depends on the number of copies of the SMN2 gene they possess. People who have 2-3 copies (Type II SMA) make more protein and survive longer, but can never walk. Those with 3-4 copies (Type III SMA) usually have a normal lifespan and can walk early in life but accumulate various limiting disabilities over time. Type IV SMA patients have 4 or more copies of the SMN2 gene and don’t experience effects of the disease until adulthood. Yet they often end up in wheelchairs.

Scientists understand why SMN2 does not efficiently yield functional protein: much of its RNA “message” is edited incorrectly, in a process called pre-mRNA splicing. The flaw in the protein’s production is understood. “What we don’t understand is how insufficient levels of the SMN protein in the period following development—i.e., adulthood—causes pathology in different parts of the body,” Krainer explains. “That’s why we set out to create a model in the adult mouse.”

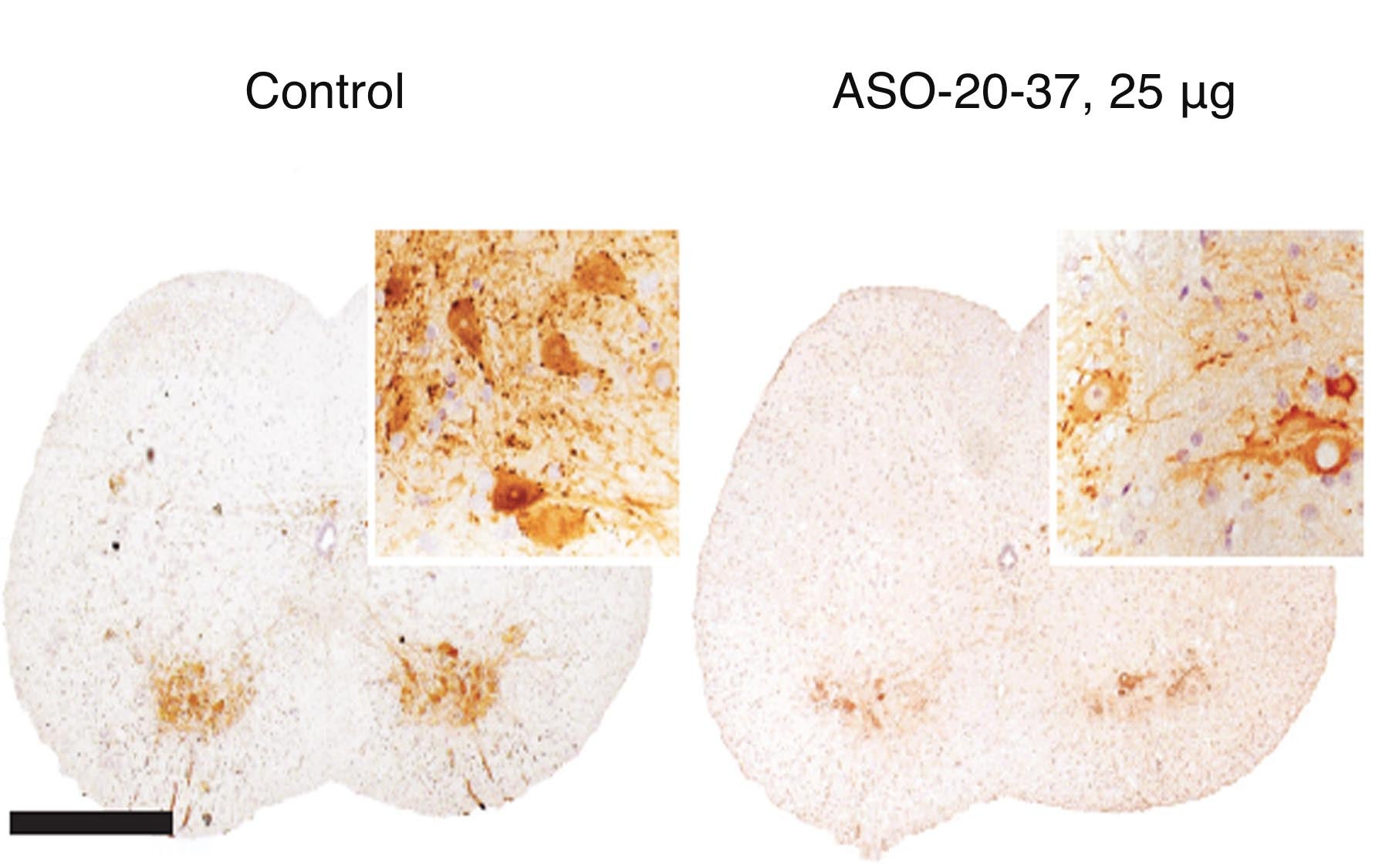

The Krainer lab’s TSUNAMI technology actually intensifies SMA’s pathological processes in mice bred to mimic the less intense forms of the illness. Thus, it can be used to recapitulate the process by which pathology manifests in different places in the body over the model animal’s lifespan.

“Our efforts to model the adult form of SMA were successful,” says Kentaro Sahashi, M.D., Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher and neurologist who is first author of the team’s new paper. “We observed delayed onset of motor neuron dysfunction; we noted also that SMN2 mis-splicing increases during the late stages of SMA, likely accelerating its progression in the body. We noted, importantly, marked liver and heart pathologies that were related to SMA’s progression in adults.”

Drs. Sahashi and Krainer added: “Perhaps most encouraging, our mouse model suggests that only moderate levels of SMN protein are needed in the adult nervous system for normal function. This means that there may be a broad time window in adult Type IV SMA patients in which to intervene therapeutically.”

Dr. Krainer and colleagues, together with Ionis Pharmaceuticals, have identified and characterized an antisense oligonucleotide drug that is currently in Phase 2 clinical trials.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

The research described in this release was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the SMA Foundation, and the St. Giles Foundation.

Citation

“Pathological impact of SMN2 mis-splicing in adult SMA mice” is published online ahead of print September 9, 2013 in EMBO Molecular Medicine. The authors are: Kentaro Sahashi, Karen K.Y. Ling, Yimin Hua, J. Erby Wilkinson, Tomoki Nomakuchi, Frank Rigo, Gene Hung, David Xu, Ya-Ping Jiang, Richard Z. Lin, Chien-Ping Ko, C. Frank Bennett and Adrian R. Krainer. The paper can be viewed online at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/emmm.201302567/abstract.

Principal Investigator

Adrian R. Krainer

Professor

St. Giles Foundation Professor

Cancer Center Program Co-Leader

Ph.D., Harvard University, 1986