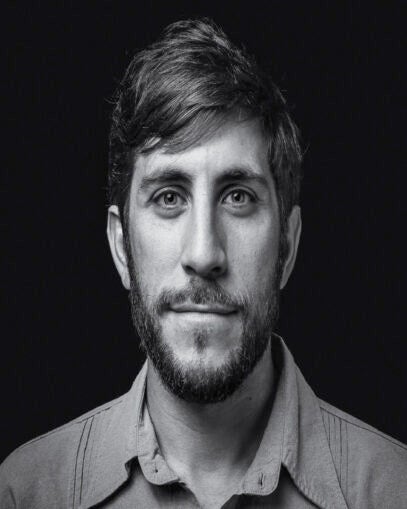

In June 2023, the Banbury Center welcomed practitioners, policy makers, community representatives, and ethicists for “Developing an Ethical Framework for Psychedelics Research and Use.” During the meeting, I had the opportunity to meet with Eduardo Schenberg, Ph.D. Dr. Schenberg is a neuroscientist and the founder of Instituto Phaneros, a Brazilian nonprofit institution that focuses on the development of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to both treat individuals with psychiatric disorders, and educate health professionals. He received his bachelor’s degree in biomedicine and his master’s degree in psychopharmacology from Universidade Federal de São Paulo. He earned his Ph.D. in neuroscience from Universidade de São Paulo. We spoke about his work bridging science and traditional knowledge and practices through the study of the Amazonian medicine ayahuasca.

Can you tell me about what you do in, more or less, two sentences?

My research tries to bridge ways of knowing – from the scientific to the Indigenous.

What is your favorite part about what you do? What gets you excited to go to work?

My work is intellectually stimulating, and it inspires hope within me that we will be able to help millions of people in the long-term.

What are some of the challenges you face in your work?

The biggest challenge is likely the bureaucracy and strict controls when doing clinical research with human subjects using Schedule I substances. We need to import and export these substances to and from different countries, which creates huge limitations – the research is more expensive to do, and it is done more slowly. It becomes so difficult that it does make us want to give up sometimes.

What is a common misconception about your work?

There are a few. In regards to Indigenous knowledge, people tend to have a prejudice that Indigenous knowledge is unscientific. In regards to scientific knowledge, people tend have this understanding that it contradicts or disregards other ways of knowing.

What sparked your interest in developing safer and better psychiatric treatments for people with conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

Well, I think it’s quite clear at this point – it’s almost unanimous in the literature – that we are facing a global mental health crisis. I see the crisis as very worrying, and it is predicted it to become even worse because of climate change, which is a huge threat to future generations. I’ve dealt with mental health issues, and I have close friends and family who have as well. Most people know someone who has suffered from mental health issues. That’s what motivates me – compassion for other people and the desire to make a difference.

This is your first time at the Banbury Center. What do you think of the meeting so far?

The meeting has a huge problem – it’s too short! [laughs]. I’ve really enjoyed it; the setting is amazing. I have, like, five hours of jet lag – I came from Lisbon – and I’ve been waking up super early, enjoying walking around, going to the beach, and listening to the birds. The quality of the presenters and the structure of the interactions have made this a really inspiring and amazing experience.

Has there been a general topic or discussion that you’ve particularly enjoyed?

I would say the epistemic and ontological issues related to Indigenous and scientific knowledge.

What do you consider to be the most defining moment of your career thus far?

Wow. That’s a big one. Perhaps it was in the Amazon, at the Second Indigenous Ayahuasca Conference, when an Indigenous leader looked me in the eyes and – in a soft way, with candor, but also fear – he asked me, “Why do you think you should study the brain? We need to study people.”