At first glance, Uplands Farm—12 carefully tended acres about a mile east of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) campus—resembles farms you might have seen before. Orderly rows of corn dominate the fields, sharing space with sorghum, eggplants, and other crops. Three greenhouses shelter young plants, extending the growing season so they can flourish in chilly New York springs. Farmhands water and fertilize the crops, accompanied only by birds, woodchucks, or the occasional hiker who has strayed from the nearby nature preserve.

A closer look, however, reveals the little things that set this farm apart from those whose plants are destined for market.

Inside the greenhouses, food crops share space with a slender flowering plant called Arabidopsis, long a favorite of genetic researchers but seen by most people as a weed. Sophisticated growth chambers give scientists precise control over plants’ environments, mimicking temperature, day length, and atmospheric conditions from around the world. They also house tubs of the humble aquatic plant Lemna, commonly known as duckweed. Often mistaken for pond scum, duckweed is the world’s fastest-growing flowering plant, and it shows great promise as a source of protein and fuel.

Out in Uplands Farm’s fields, where CSHL plant biologists test the roles of different genes, crops lack the uniformity of large-scale agricultural operations. Short plants stand next to towering ones. Some boast fat corn cobs or abundant grains while others appear much scragglier.

Perfect-looking produce is not the priority, says Farm Manager Kyle Schlecht. His team supports CSHL’s five plant biology labs by overseeing the fields, greenhouses, and associated facilities. “The goals here are different than on a normal farm, where you want the materials you’re going to sell to look really good,” Schlecht says. “What we want is to get the plants to flower as quickly as possible, so the researchers can cross strains faster.”

The goals differ because Uplands Farm’s plants have to do more than supply food for the coming months. They’re here to enable discoveries that growers need to feed and fuel the world far into the future.

Nature of change

As the planet changes and its growing population increases demand on food systems, agriculture is already being forced to adapt. To support that effort, CSHL scientists are finding ways to amplify crop yields and boost plants’ resilience in the face of extreme weather, depleted or contaminated soils, and other challenging conditions.

Many discoveries’ impacts are easy to recognize. For example, sorghum is an important global source of food, livestock feed, and biofuel. Uplands Farm’s fields have grown sorghum crops that produce an increased amount of grain. Working with the USDA Agricultural Research Service, CSHL Adjunct Professor Doreen Ware’s team traced the crops’ higher seed number to a genetic change that reins in a particular hormone.

Equally influential advances are happening on a less visible scale. CSHL biologists investigate the very molecules that control how plants grow and develop. As they study how plants respond to environmental changes, they uncover knowledge that can help breeders optimize future crops. At the same time, they illuminate fundamental principles of biology, sometimes shedding light on how human cells work, too.

For Ware, plants’ extraordinary adaptability is both a wonder and a complicated puzzle to solve. She says plants have a superpower. Their changeable genomes have enabled them to withstand diverse and difficult environments. Plants have harnessed that superpower to flourish in their day-to-day lives and adapt over time. Alongside that natural evolution, farmers have cultivated plants’ genetic diversity by selectively breeding those strains that are tastier, more productive, and easier to manage.

As adaptable as they are, plants can’t keep up with our planet’s current rate of change on their own. It’s too much to expect the crops we rely on to cope with rapidly warming temperatures, prolonged droughts, or emerging pests. That’s why scientists study both how plants have evolved and what limits their productivity and survival. “We have to understand what nature has captured,” Ware says. “And what it hasn’t captured, we may have to engineer.”

Roots of knowledge

CSHL has a long history of uncovering the sources of plants’ diversity. Ware calls that work “the raw foundation for how modern breeding is done.” Early CSHL plant geneticist George Shull played a crucial role in developing hybrid corn. Today, it accounts for about 95 percent of the U.S. maize crop. And perhaps the most famous plant biologist from CSHL’s long history, Barbara McClintock, identified the “jumping genes” responsible for the different colors of Indian corn. These transposons were later found to comprise a large part of the human genome, sometimes contributing to diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration.

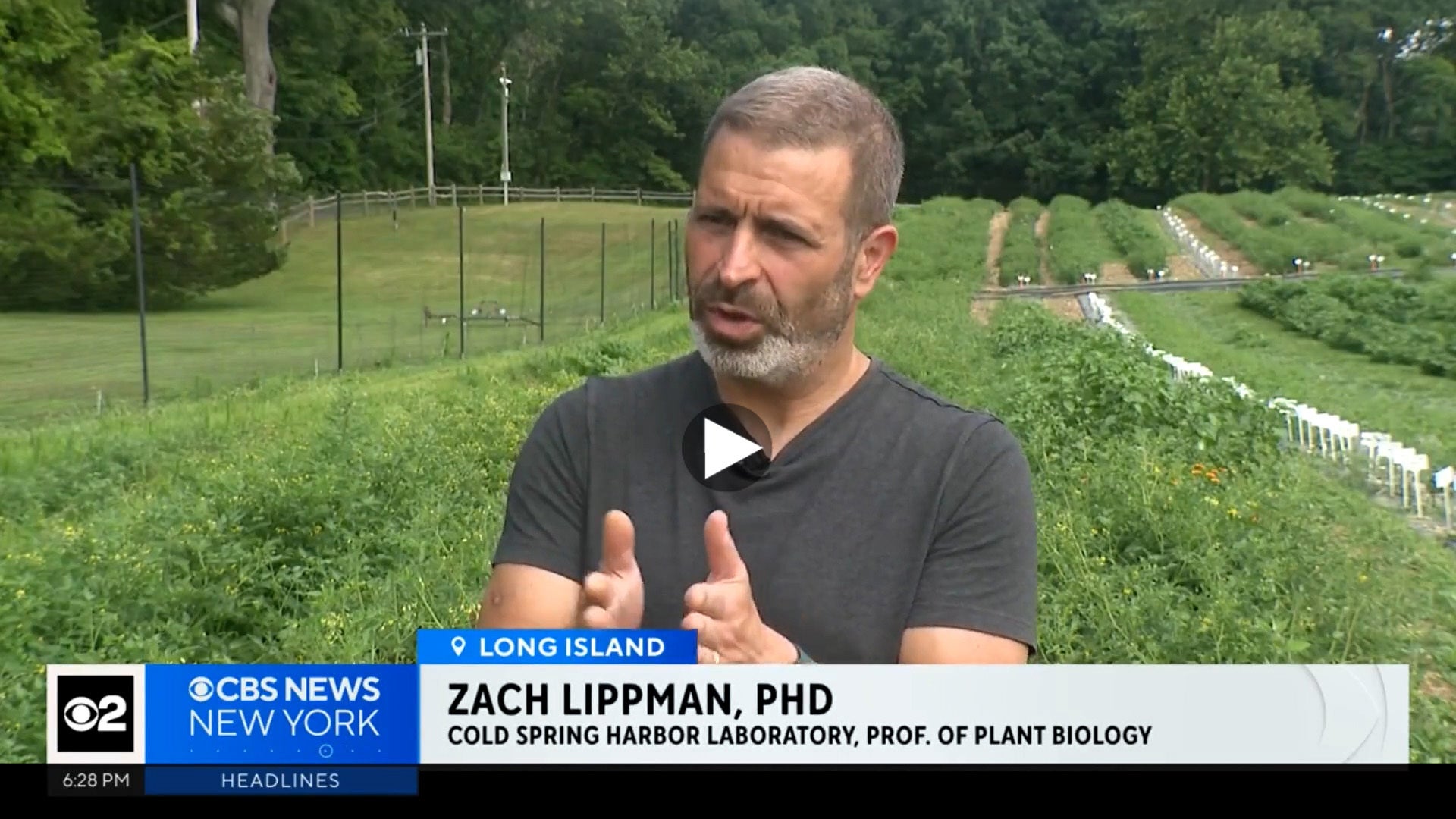

Fast-forward decades. Current CSHL Professors Rob Martienssen and W. Richard McCombie were part of the team that sequenced the very first plant genome—that of Arabidopsis. Since then, scientists have sequenced the genomes of economically important crops, like maize, rice, sorghum, and grapevine. Martienssen, McCombie, Ware, and CSHL Professor Thomas Gingeras each made major contributions to these projects. Furthermore, CSHL Professor Zachary Lippman’s work with the genomes of so-called orphan crops, like the tomato relative groundcherry, has created opportunities to scale up their production and diversify our diets.

Analyzing plant genomes is also key to zeroing in on other useful genetic features, like those that make crops resistant to disease. At CSHL, scientists tweak specific genes in their labs to see what happens at the molecular level. They then return to Uplands Farm to test their most promising changes. Have they made a strain that can handle droughts, survive in low-nitrogen soil, or produce more food?

Take a virtual tour of CSHL’s state-of-the-art growth chambers with plant biologist Ullas Pedmale.

Depending on their questions, they may choose to grow their plants inside greenhouses or in Uplands’ custom growth chambers. There, researchers can precisely control everything from carbon levels to temperature to season. The growth chambers enable CSHL Associate Professor Ullas Pedmale to investigate how plants sense and respond to sunlight and climate conditions. When plants find themselves in too much shade, they redirect energy from their roots to their shoots, leaving them more vulnerable to drought, floods, wind, and lower crop yield. Pedmale aims to reprogram this “shade avoidance” response so that crops can thrive even when planted closer together, paving the way for more sustainable agriculture.

Plants aren’t the only ones whose health is strongly influenced by light. It affects human health, too. Sunlight exposure drives our circadian rhythms, influencing sleep, mood, metabolism, and disease risk. A light-sensitive protein that Pedmale studies in Arabidopsis is evolutionarily related to similar proteins in humans that regulate these processes. His work investigating how that protein is regulated in plants could inform new strategies for treating or preventing disorders tied to our biological clocks, such as diabetes and cancer.

Seeds of innovation

In addition to investigating resiliency, CSHL scientists look for ways to make plants more productive. Professor David Jackson’s lab has discovered multiple avenues to get more corn on a cob. They’ve found genetic manipulations that make corn ears longer or pack in extra rows of kernels. Jackson says the impact of these discoveries can be amplified thanks to modern gene editing methods.

With tools like CRISPR, researchers can quickly introduce a genetic change to plants that have adapted to growing in one or multiple environments. “Maize already has a lot of diversity,” Jackson says. “It’s not a matter of just making the perfect corn for Iowa. Everyone has their own adapted strain.” Jackson and his team have found that manipulating a single gene can add kernels to cobs. These genetic tweaks could also improve yields in other staple crops, such as rice.

However, genetic changes don’t always have the same effects across different plants. Work from Zach Lippman’s team offers insights into this very issue. Their rows at Uplands Farm are filled with nightshades like tomatoes and eggplant. In exploring the mechanisms that control branching and flowering, Lippman has shown that duplication of genes across evolutionary history can have profound effects. “It’s really important in the context of engineering traits for agriculture,” he says. “The type of mutation you might create in tomato is not necessarily the best type of mutation for eggplant or pepper, because of how gene duplications have evolved.”

How can breeders anticipate and overcome these effects? For starters, Lippman and colleagues have assembled a pan-genome made up of the genomes of 22 different species of nightshade. What’s more, the “statistical genetics” methodology that Lippman’s collaborator David McCandlish has applied to analyze relationships between plant genes may enable similar studies in other organisms. McCandlish says that could be useful for anticipating and potentially alleviating the side effects of certain drugs.

Additionally, studying the molecules that regulate genes in plants can help explain why certain mutations put people at risk for disease. For example, an ancient protein called Dicer is known to help plants defend themselves against viruses. The Martienssen lab has shown that it’s also important for driving the domestication of maize, and even for maintaining genome stability in mammals. People born with mutations in the gene for Dicer are more likely to develop several kinds of cancer. Martienssen’s studies could inform cancer research aimed at developing new tools for treatment or immunization.

Indeed, CSHL plant biologists’ collaborations across research areas are often remarkably synergistic. The resulting advances can touch many fields. In a sense, all of those innovations have roots at Uplands. Here, biologists and farm technicians work to help science and society meet the challenges of tomorrow. Their quiet little farm is already having an outsized impact on the world.

Written by: Jennifer Michalowski, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455