Barbara McClintock missed an important call on the morning of October 10, 1983. She had chosen “to be free” of the interruptions that came with owning a telephone, and so it was her students and colleagues who told her that she had received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

“That’s nice,” she said with little more than a brief smile.

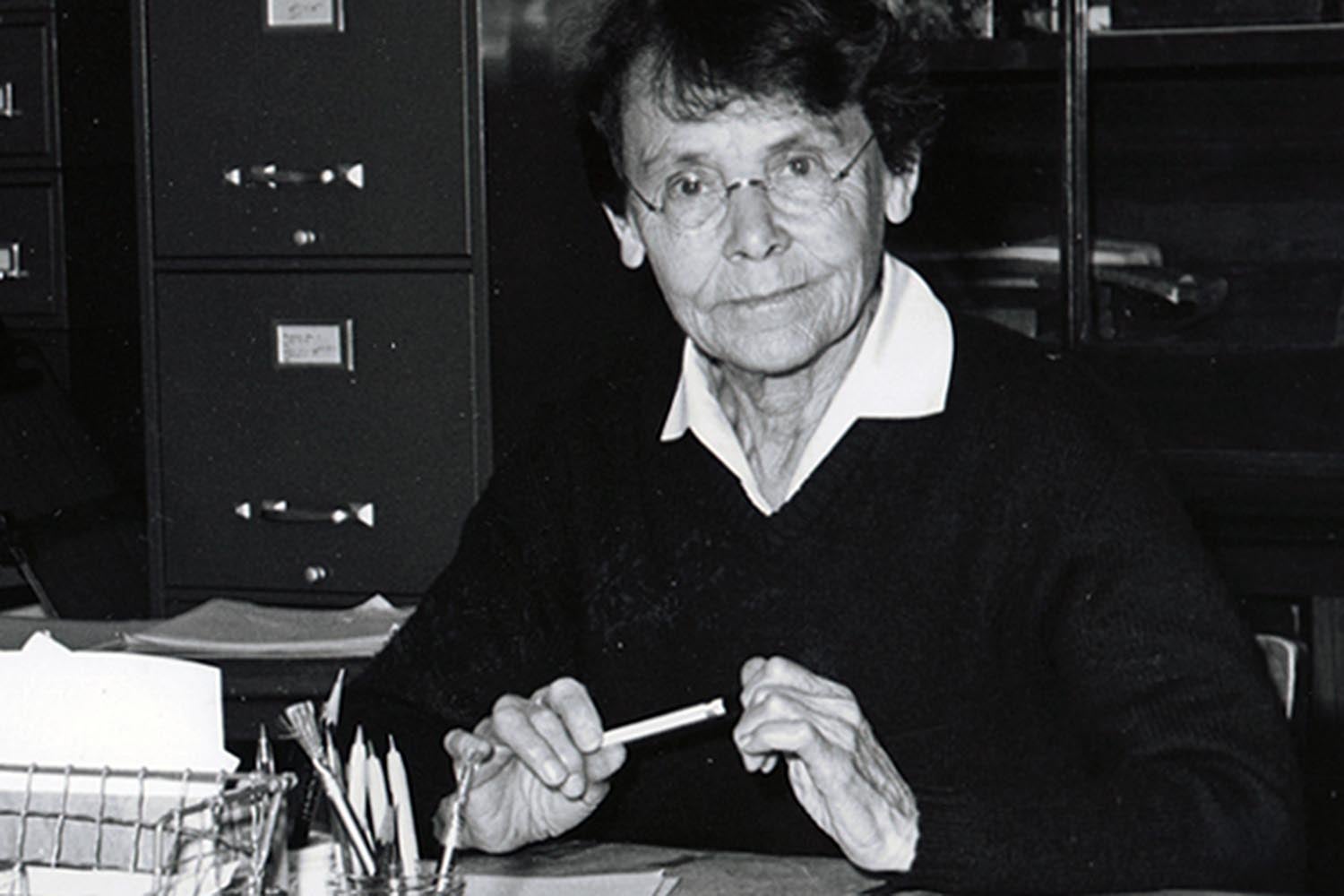

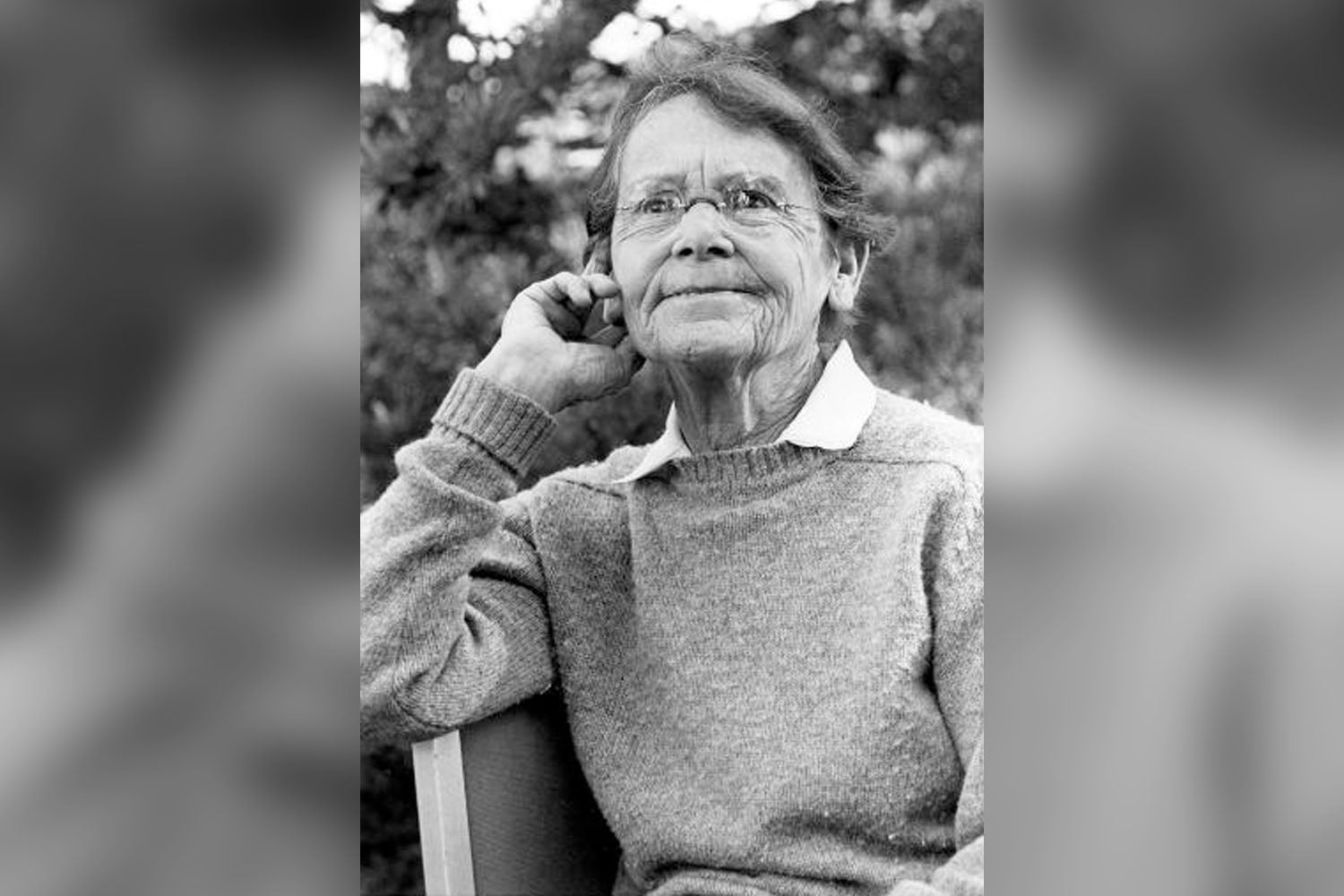

At age 81, she was the first woman to win the award unshared, but she wasn’t about to let the inevitable press blitz get in the way of her morning routine. With reporters in tow, she set off to pick the black walnuts that grew on the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) campus.

A consistent theme throughout McClintock’s life was to insist on doing what she wanted when she wanted to do it. Renowned molecular biologist Nancy Hopkins reminisced that this sort of freedom didn’t always come so easy for McClintock. Hopkins met her as a graduate student in the 1970s during summertime visits to CSHL.

“At the time… It seemed like she needed somebody to talk to,” Hopkins said. “She’d tell me about these very difficult years when it was so difficult for a woman scientist to be recognized. Of course, I was young and biology was just so wonderful and I didn’t want to hear about how hard she’d had it… but we became friends… and I wish I could talk to her now with the understanding I have now.”

This Women’s History Month, we celebrate one of CSHL’s most inspiring scientists by chronicling her pursuit of both personal and scientific freedom.

McClintock discovered her passion for science during her high school years, when the field of genetics was still in its infancy.

“There was a burst—one of those wonderful periods in biology when so much was learned,” she’d later explain. “I am just so enthused by what was discovered that I feel that I’m in on it!”

She was intent on learning more about genes, but her mother opposed Barbara’s higher education. Sara McClintock was worried that becoming a scientist would make her daughter “unmarriable.” But Barbara’s father supported her and she would not be deterred. She graduated from Erasmus Hall High School early and enrolled in Cornell University in 1919.

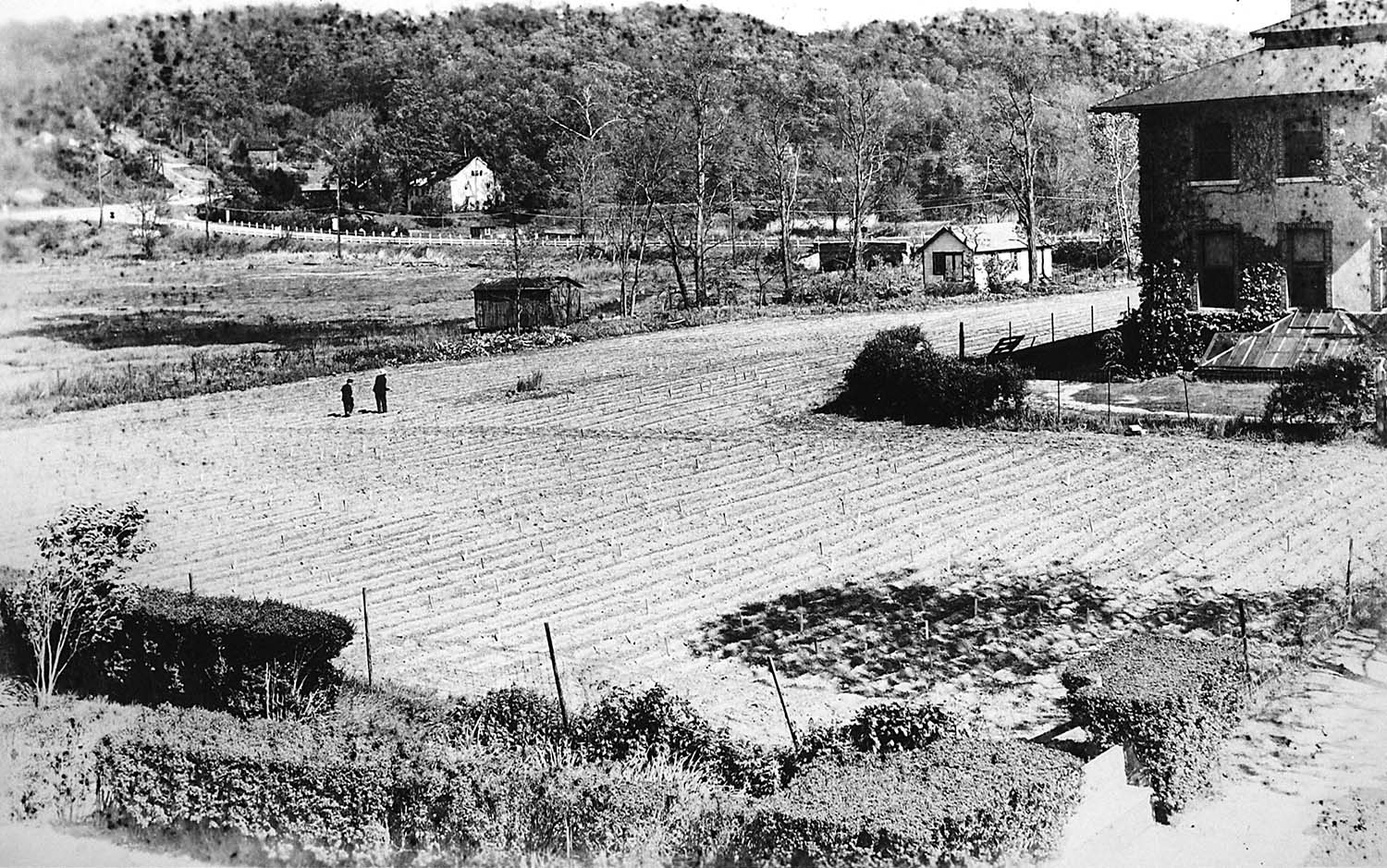

For the next ten years, McClintock divided her time between labs and fields, focusing on any subject that interested her. She learned, just as Gregor Mendel did, that plants were ideal for puzzling out the secrets of genes and heritable traits. Understanding chromosome structures under the microscope, she delved into cytogenetics as a graduate student at Cornell and then as a research assistant for the university’s labs. McClintock was among the first scientists to describe how the recombination of chromosomes seen under a microscope correlated with new traits in maize plants.

In 1931, McClintock published the first genetic map for maize, showcasing how she discerned the order of three genes in a single maize chromosome.

Five years later, she became an assistant professor at the University of Missouri. However, she revealed in letters that she was being excluded from faculty meetings and lacked freedoms and opportunities that her male peers enjoyed. Not one to tolerate such limitations, she took an unpaid leave of absence in 1941 and began to hunt for a more welcoming environment.

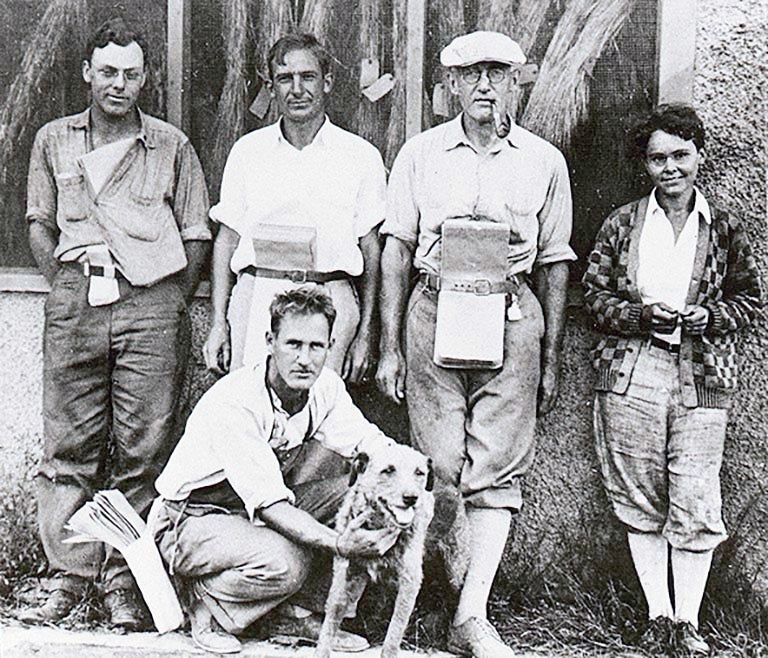

She found that freedom at the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Station for Experimental Evolution in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. In a temporary arrangement, McClintock continued her research as she saw fit in the Institution’s fields. After only a few months, station director Milislav Demerec was so impressed with McClintock that he sought to create a permanent position for her.

She is “among the first ten leading cytogeneticists of the world… with a breadth of knowledge and vision that enables her to select problems of great significance,” Demerec told Carnegie director Vannevar Bush. She began working at Cold Spring Harbor as a guest in the summer of 1941 following the Symposium.1

Three years later, in the aftermath of WWII, the Cold Spring Harbor campus was in need of new research goals. McClintock and Demerec designed a Department of Genetics—an action that would eventually turn the waterside campus into one of the world’s leading hubs for genetics research.

In 1950, McClintock’s investigation of unstable inheritance of mosaicism in maize plants culminated in “The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize” published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. McClintock presented the work at the 1951 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology, introducing her concept of “controlling elements”—or jumping genes. Unfortunately, many of her peers were skeptical that McClintock’s results were sound.2

“They said I was crazy—absolutely mad,” she’d later tell people. But true to form, she pressed on with her research unabated. “When you know you are right you don’t care!”

After cutting ties with Carnegie in 1962, the Cold Spring Harbor station was reborn as the independent not-for-profit known as Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). McClintock stayed on in the Carnegie’s Genetics Unit at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, forever one of the institution’s most prestigious employees.3 Her presence helped draw other significant scientific talent, including Nobel laureate Al Hershey and Martha Chase.

McClintock became the first woman to be awarded the National Medal of Science in 1970. She remained at CSHL for many more years, mentoring young scientists such as Nancy Hopkins and Robert Martienssen. Today, Martienssen carries on McClintock’s research on epigenetics and “jumping genes” as a CSHL professor and HHMI investigator. He was honored with the Barbara McClintock Prize for Plant Genetics and Genome Studies in 2018.

“I am very much interested in the nature of changes in the genome when the genome meets something very unexpected,” McClintock said to a room full of international dignitaries and scientists during her Nobel lecture on December 8, 1983.

It was just two months after she found out she won the Nobel prize. She concluded her talk 40 minutes later to resounding applause. Nobel officials said her work was “the second great discovery” in genetics, closely following the work of Gregor Mendel, the so-called father of genetics.

McClintock died in 1992. She left behind an inspiring legacy, not just for women, but for scientists facing all kinds of barriers and adversity.

“There have been many accounts and writings regarding McClintock’s intense focus, her solitude in the pursuit of scientific questions, and her wish for privacy,” CSHL Professor and HHMI Investigator Robert Martiennsen recently wrote. “While her intensity and scientific focus were not exaggerated, Barbara McClintock was also well known as a generous mentor to many, particularly to graduate students, postdocs, and new investigators, and especially women in the sciences.”

McClintock’s spirit permeates the campus she called home for five decades. She once said that she was so free to study what she wanted at CSHL that she’d have been fired had she worked anywhere else. Her impact on the culture of CSHL cannot be overstated. Portraits of her are dotted across the campus. The “animal house” building that once stood a few steps away from her historic maize fields was renamed the McClintock Laboratory. And her dogged pursuit of interesting ideas, no matter where they lead, animates today’s CSHL researchers.

On May 25, 2021 the following corrections were made to the story:

1 The story originally stated: “McClintock became a full-time staff member in 1942.”

2 The story originally stated: “McClintock presented the work at the newly-minted Department of Genetics’ annual symposium, introducing biology to her concept of “controlling elements”—or jumping genes.”

3 The story originally stated: “McClintock stayed as one of the lab’s first and most prestigious employees.”

Written by: Brian Stallard, Content Developer/Communicator | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455