For several years now, CSHL’s Adrian Krainer has devoted his expertise in alternative splicing—a cellular process for editing RNA—towards fixing the genetic glitch that underlies spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a neuromuscular disease that’s currently the No.1 genetic cause of death among children under the age of two. Read more in this Harbor Transcript profile of Dr. Krainer (pdf).

Earlier this month, a team that include Krainer’s CSHL group and researchers at Ionis, Genzyme and Harvard Medical School reversed symptoms of severe SMA in mice by delivering chemically modified RNA segments called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) into their spinal cords.

Last year, Krainer and his collaborators at California-based Ionis Pharmaceuticals were able to reverse symptoms of type III SMA, a relatively mild form of the disease in mice.

As the team describes in a paper that was published in Science Translational Medicine, injecting ASOs into the cerebral lateral ventricles—brain structures that contain spinal fluid and lead into the spinal cord—of the mice lead to “improvements in muscle physiology, motor function, and survival.” The researchers think that this central nervous system-directed ASO therapy might be a practical route for delivering this therapeutic in the clinic.

Genomics study uncovers potential drug target for schizophrenia

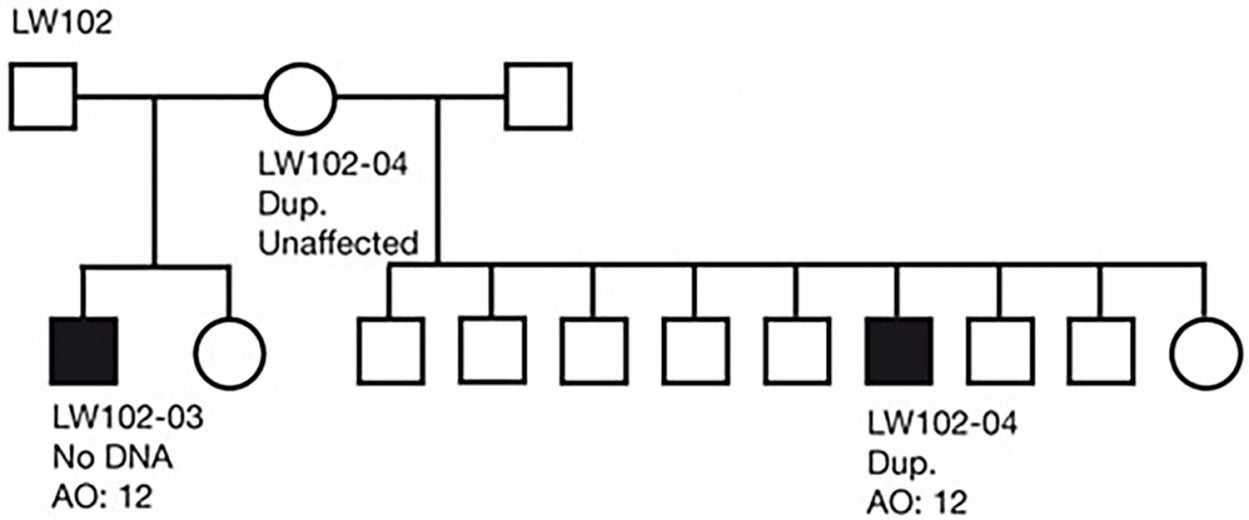

Neuroscientists in CSHL’s Stanley Institute for Cognitive Genomics are part of a team of researchers from 14 different institutions that has identified a rare genetic mutation that might offer clues to treat schizophrenia.

In the new study, which involved 8,290 schizophrenia patients and 7,431 healthy controls, the researchers discovered that genomic regions at the tip of chromosome 7q were 14 times more likely to be duplicated in schizophrenic individuals than in healthy people. These genetic alterations are called copy number variations (CNVs) because they change number of copies of a gene, thereby causing variation between individuals.

As described in the report, which was published in Nature, the CNVs detected by the team turned out to impact a gene called VIPR2, which is important for brain development and behavioral processes, including learning and timing of daily activity. The scientists found that the patients with schizophrenia had higher activity levels of this gene than healthy people did.

What makes this discovery particularly exciting is that this is the kind of gene whose activity can be easily modulated using synthetic molecules that already exist, according to team leader Jonathan Sebat, Ph.D., a former CSHL scientist who is now at the University of California in San Diego.