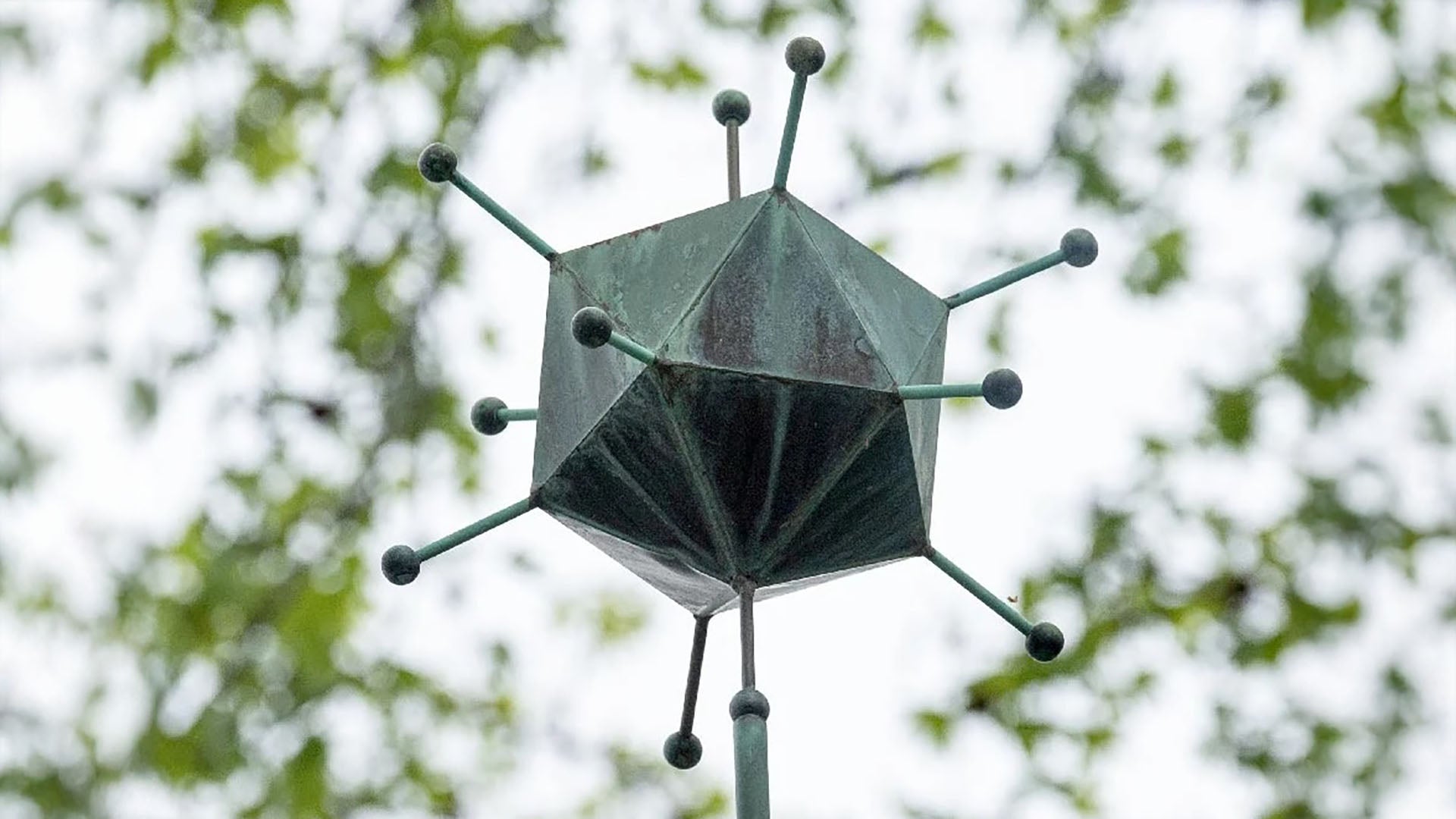

When the weather’s right, you can find any number of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) students, faculty, and staff around the gazebo on Bungtown Road. The spot’s popularity is undoubtedly owed to its excellent view of the harbor. But crowning the gazebo is an homage to something arguably just as important to CSHL as its inspiring surroundings—an adenovirus.

You may ask yourself, “What’s an adenovirus?” Well, it’s one cause of the common cold. But that’s not what makes it interesting, nor why one sits atop the gazebo. For that we need to go back, back to the Laboratory of the late ’70s and early ’80s.

Just imagine: rock, disco, and new wave ruled the radio. Aviator glasses had entered the mainstream. The Beatles were never getting back together. And the National Institutes of Health’s ‘War on Cancer’ was in full swing. That last part’s important, because adenovirus only gives humans the common cold. In mice, it causes cancer.

It’s unknown when adenovirus first arrived at CSHL. But the first samples used for research were brought by visiting scientist Ulf Pettersen in 1972. By 1974, a group including CSHL’s Terri Grodziker and alumni Phillip Sharp and Joseph Sambrook had published the first of several studies on adenovirus hybrids. Their fundamental research sparked collaborations across the country aiming to expand adenovirus’ use as a model for studying cell division, with an eye toward potential cancer therapeutics.

But what about the gazebo? Around the same time the adenovirus was taking cancer research by storm, the Laboratory was deep into a major expansion project. This included new offices, lab renovations, on-campus housing, and a facility to finally solve CSHL’s then-perennial wastewater problems.

Completed in 1976, the water treatment plant was built into the hill beneath Bungtown Road. A portico sheathed in wooden shingles was constructed to cover the facility’s east-facing facade, topped by a brick patio that draws visitors in toward the gazebo, its built-in seating, and, of course, the fantastic view. The copper adenovirus, held aloft by an anthropomorphic wooden finial, was installed that same year.

In 1977, the humble adenovirus would earn its stripes for its key role in Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp’s discovery of split genes and RNA splicing. Their work set the stage for the development of nusinersen (Spinraza), the first FDA-approved drug to treat spinal muscular atrophy, by CSHL’s Adrian Krainer in 2016. It also earned Roberts and Sharp the 1993 Nobel Prize.

But adenovirus’ scientific value didn’t end there. Hybrid adenoviruses played a key role in then-postgraduate-student Bruce Stillman’s early discoveries on the origins of DNA replication, presented at the 1979 CSHL Symposium. (Stillman is now CSHL President and CEO.) They would also see extensive use in CSHL’s landmark cancer studies throughout the 1980s. Today, they remain a valuable tool across numerous fields of research—as a mode of delivery in early COVID-19 vaccines being a recent example.

Oxidation aside, the little copper adenovirus is still going strong, too—a monument to its enormous impact on our understanding of cancer, genes, and the origins of life— overlooking inner Cold Spring Harbor.