Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Today, biologists add an important discovery to a growing body of data explaining why we’re different from chimps and other primate relatives, despite the remarkable similarity of our genes. The new evidence has to do with the way genes are regulated. It’s the result of a comprehensive genome-wide computational analysis of multiple individuals across three primate species—human, chimpanzee and rhesus macaque.

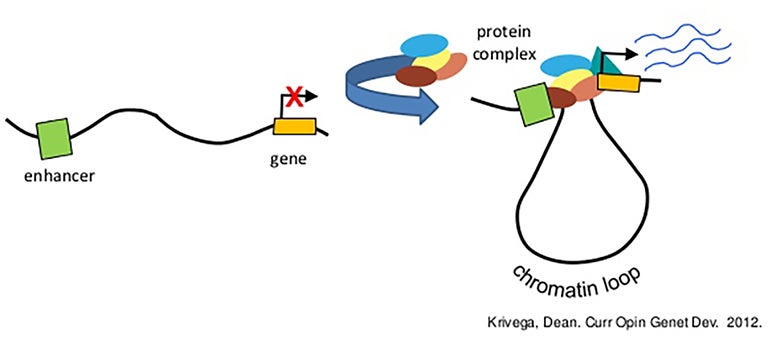

The researchers focused on regulatory DNA elements called gene enhancers and promoters. Promoters sit immediately “upstream” of genes and must be activated for the genes they regulate to be switched on. Less is known about enhancers, which can be located varying distances up- and downstream of the genes they regulate. Enhancers can be much farther away from the “gene body” than promoters, but can come close to the gene because of the looping shape of chromatin, the structure that packages the genome. Often, multiple enhancers are involved in a given gene’s activation, in combinations that differ under differing circumstances.

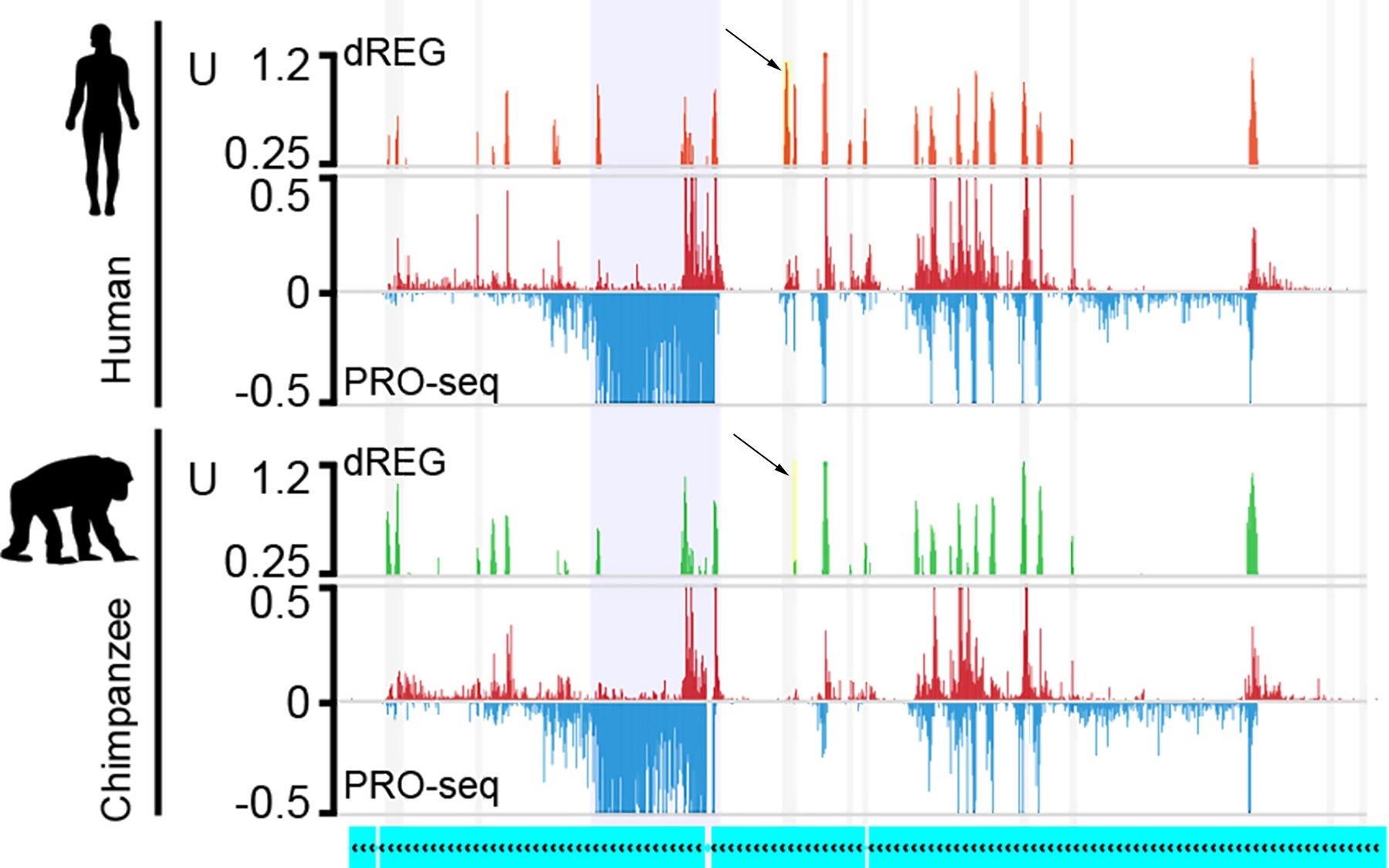

Professor Adam Siepel’s team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) with colleagues at Cornell University led by Dr. Charles Danko, used a technology called PRO-Seq to measure nascent transcription—the generation of RNA copies of genomic DNA up- and downstream of genes. It enables researchers to detect which promoters and enhancers are actively regulating a gene. They studied a single cell type, CD4+ T cells of the immune system, comparing levels of RNA copying when the cells were in quiescent and activated states in the three primate species.

The experiments revealed that while the activity of genes across the three species was quite similar in the CD4+ T cells, there were intriguing differences in the way genes were regulated. The team paid particular attention to collections of enhancers that jointly influence the expression of a target gene, as an ensemble. “These ensembles come in various sizes,” Siepel explains, “and we found that when they are large, the expression levels of the target genes tend to be stable over evolutionary time. When they are small, the expression levels are less stable.” Stability in gene expression is evidence of what scientists call evolutionary conservation—the preservation of a feature across species because of the advantage it confers.

Through careful analysis, the team identified various features that distinguish fast-evolving enhancers from slower ones. “Particularly interesting to us were cases in which large numbers of enhancers together determine the expression of a target gene,” says Siepel, who is Director of the Simons Center for Quantitative Biology at CSHL. “In these cases, the genes tend to be more stable, but we found each individual enhancer is more likely to change.” What’s under evolutionary selection is the target expression level of a given gene, which in these situations is jointly determined by the whole ensemble.

The research reveals how programs for gene expression change during evolution, leading to the differences in behavior and morphology we observe between humans and other primates. These evolutionary mysteries also offer clues about mutations that cause diseases by altering gene regulation, Siepel notes.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

Cornell University Center for Vertebrate Genomics; Center for Comparative and Population Genetics; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

Citation

Danko CG et al, “Dynamic evolution of regulatory element ensembles in primate CD4+ T cells” appears online in Nature Ecology & Evolution January 29, 2018.

Principal Investigator

Adam Siepel

Professor

Cancer Center Member

Ph.D., University of California, Santa Cruz, 2005