Genetic “fate-mapping” technologies developed by (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) Professor Josh Huang and colleagues show in exquisite detail how an important part of the mammalian brain—here, a mouse brain—self-assembles over a few short weeks during the embryonic period. In the sequence featured below, follow the emergence of the striatum, a brain area that enables information processed by the cortex to be translated into precise physical movements and actions, as mediated through the basal ganglia.

Although in anatomical terms individuals do differ in small ways, the miracle of brain development is consistency from individual to individual. The brain’s basic scaffold is the work of a genetic program that directs its assembly. The result is a brain at the species level—whether in a mouse or a human—that is highly stereotypical.

By far the most complex entity that science has so far attempted to understand, the brain in a person can sense, process, evaluate, select, even think, plan and imagine, as a consequence of structures, connections and networks that we all possess. These give rise to the extraordinary functional capacities whose secrets we are only just beginning to learn. Tiny perturbations in brain development, sometimes influenced by environmental circumstances and/or small variations in an individual’s genetic code, are almost certainly among the root causes of serious disorders and illnesses including autism, Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia.

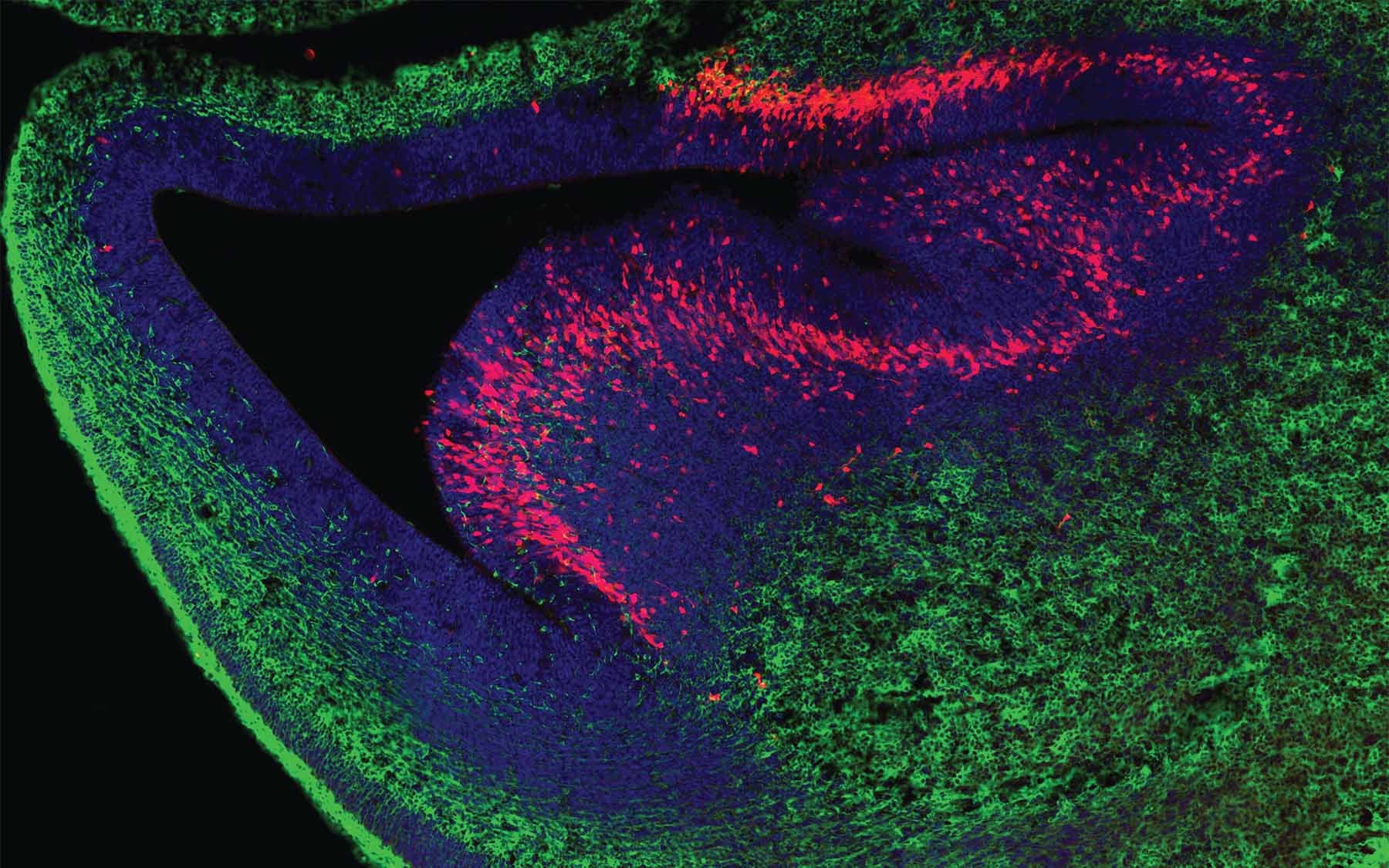

The embryonic brain begins to take shape

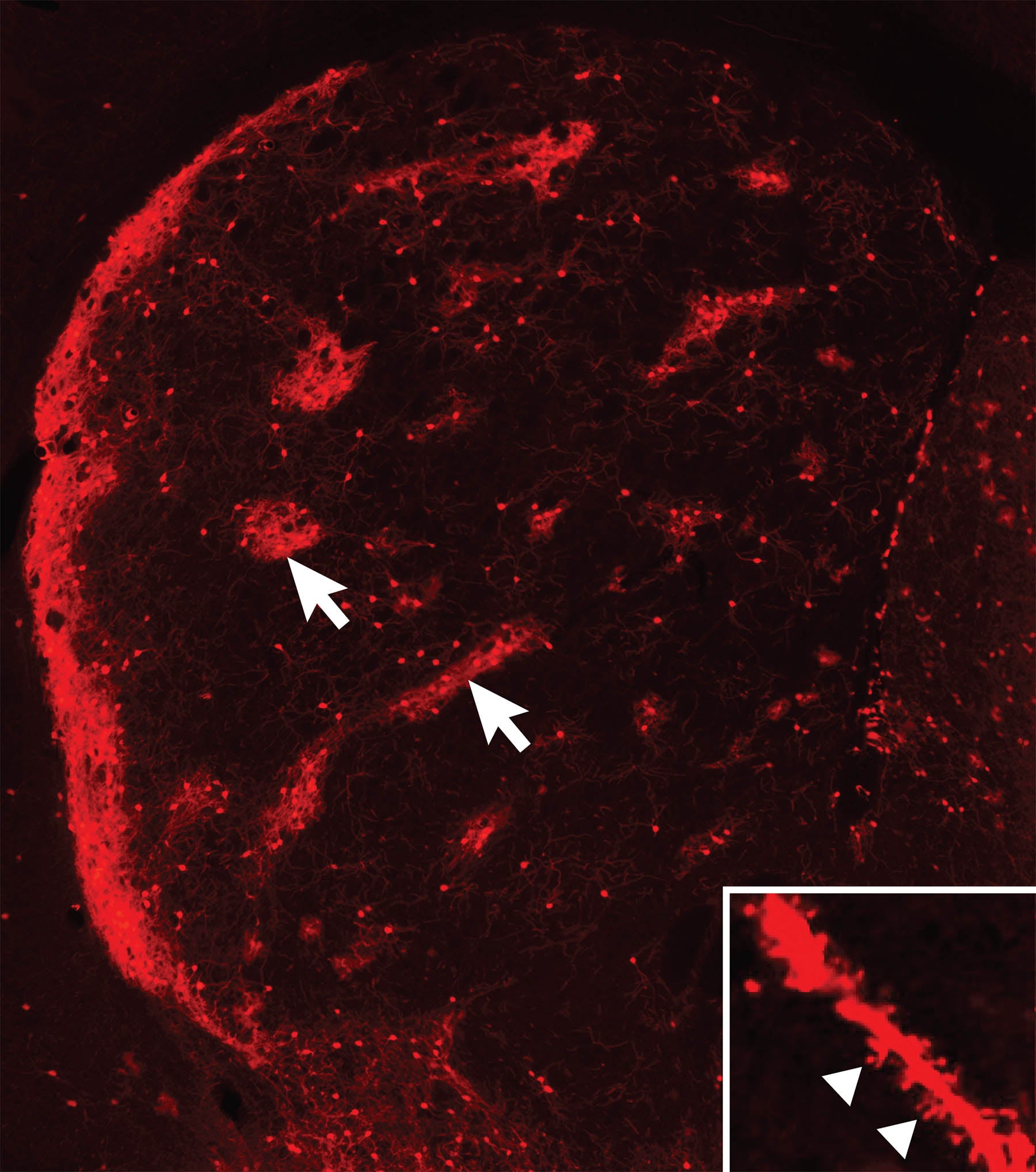

Neuronal nursery

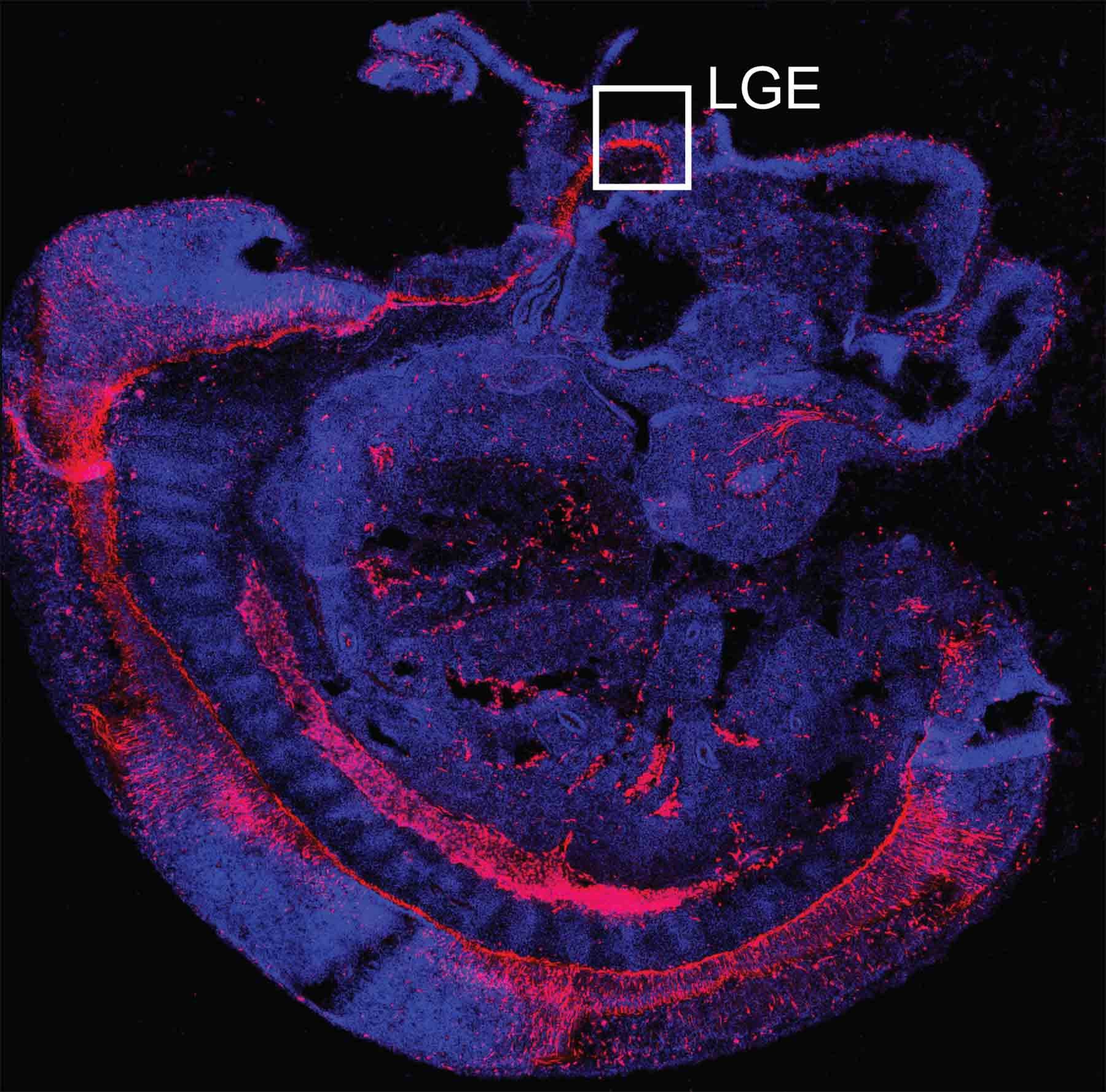

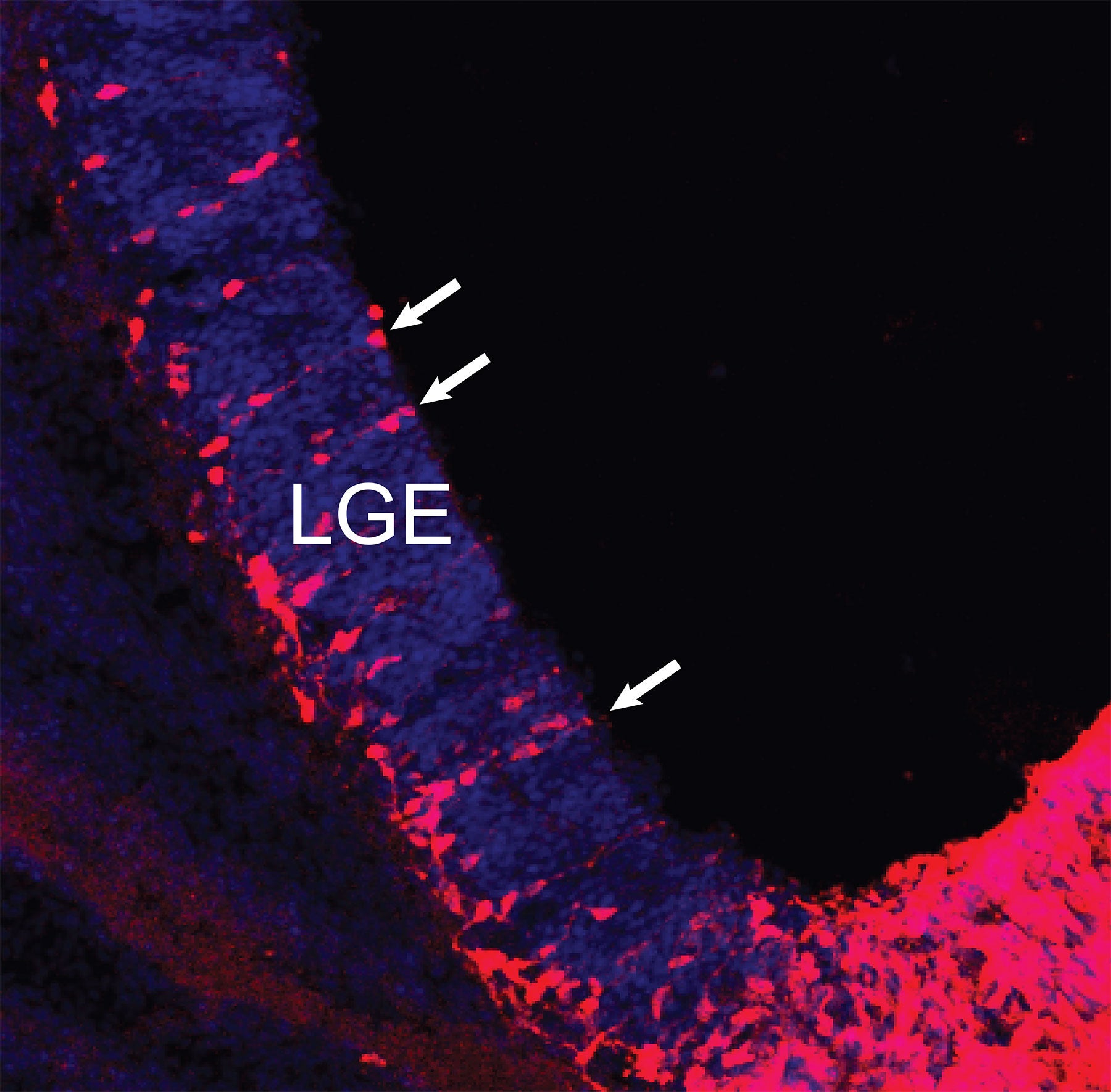

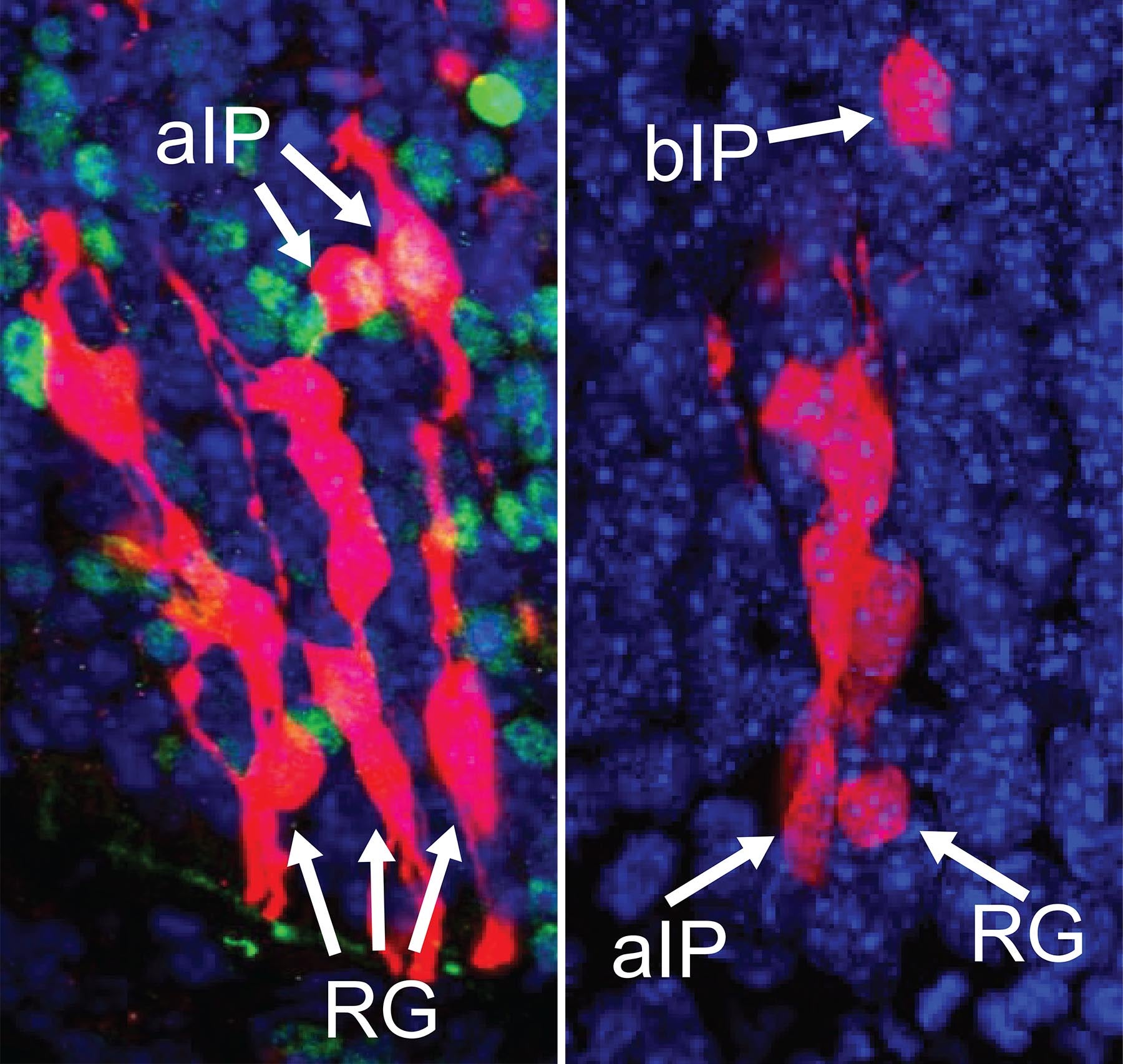

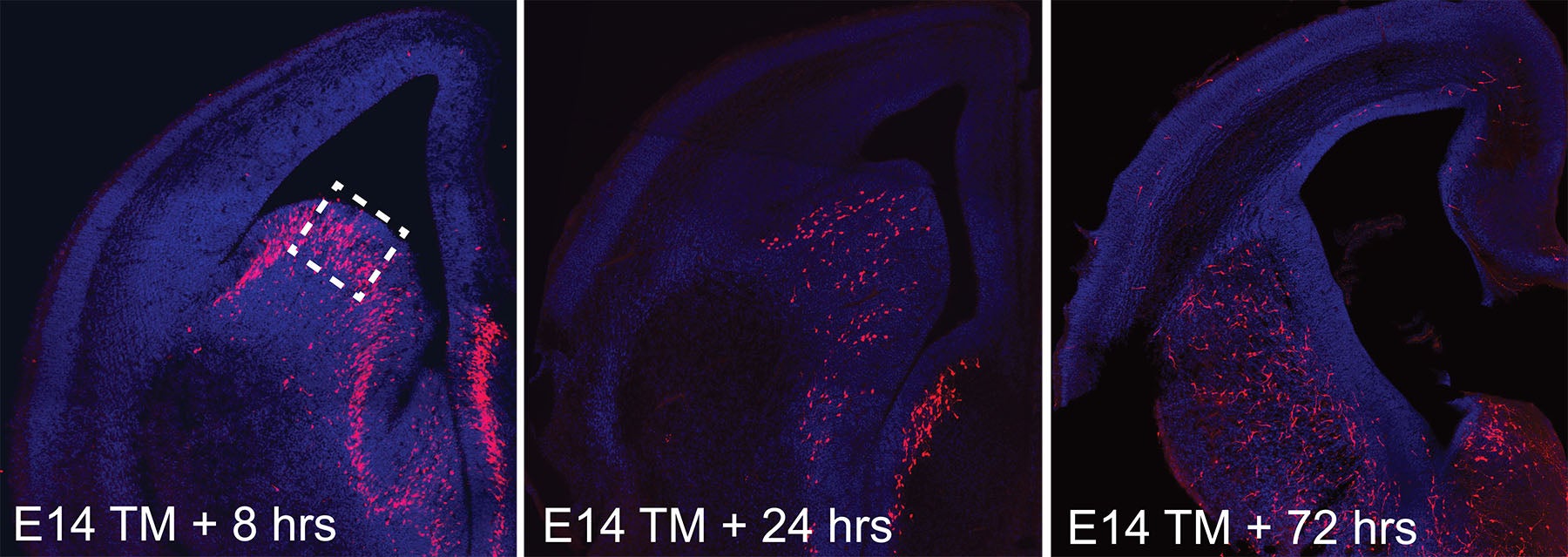

Common ancestors

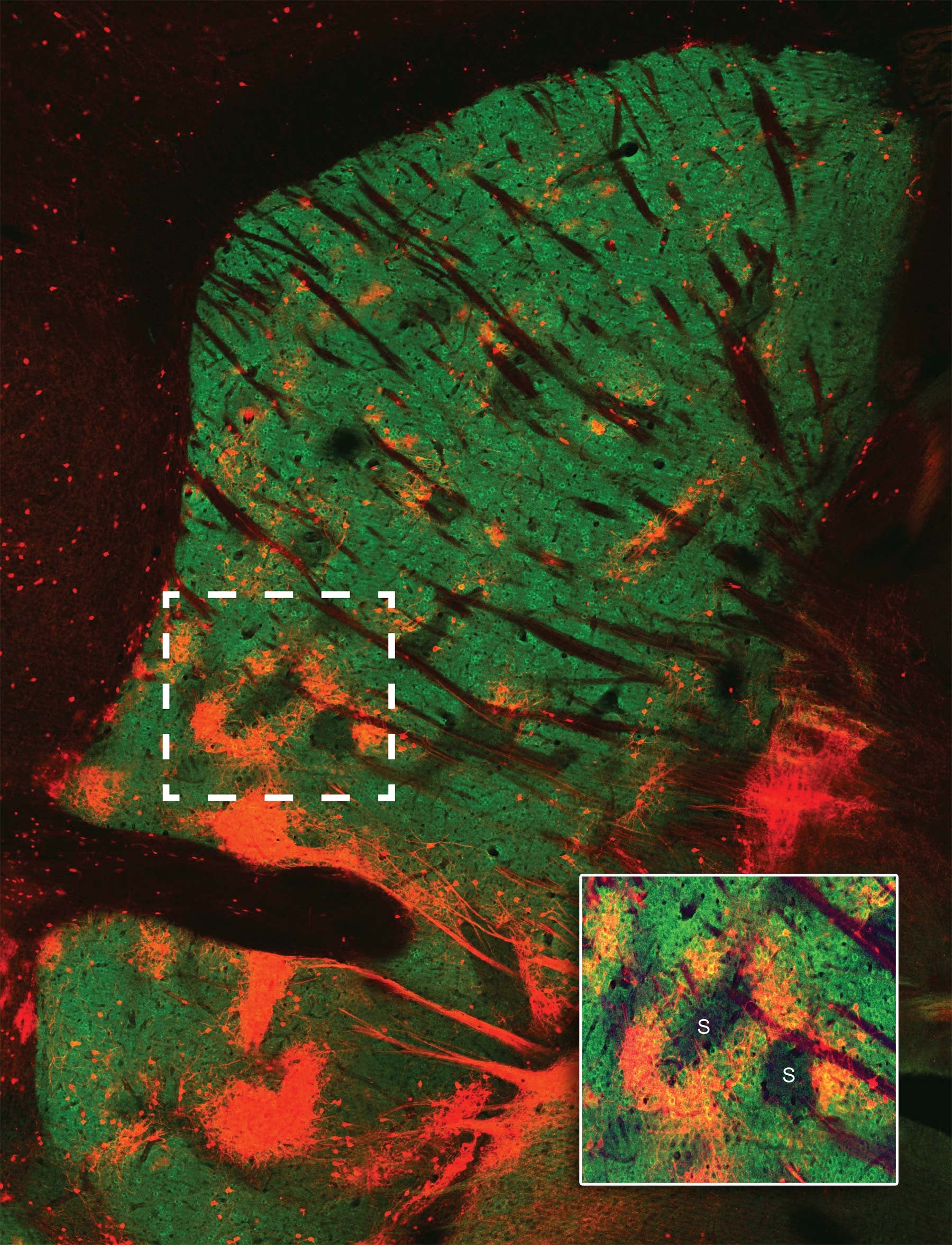

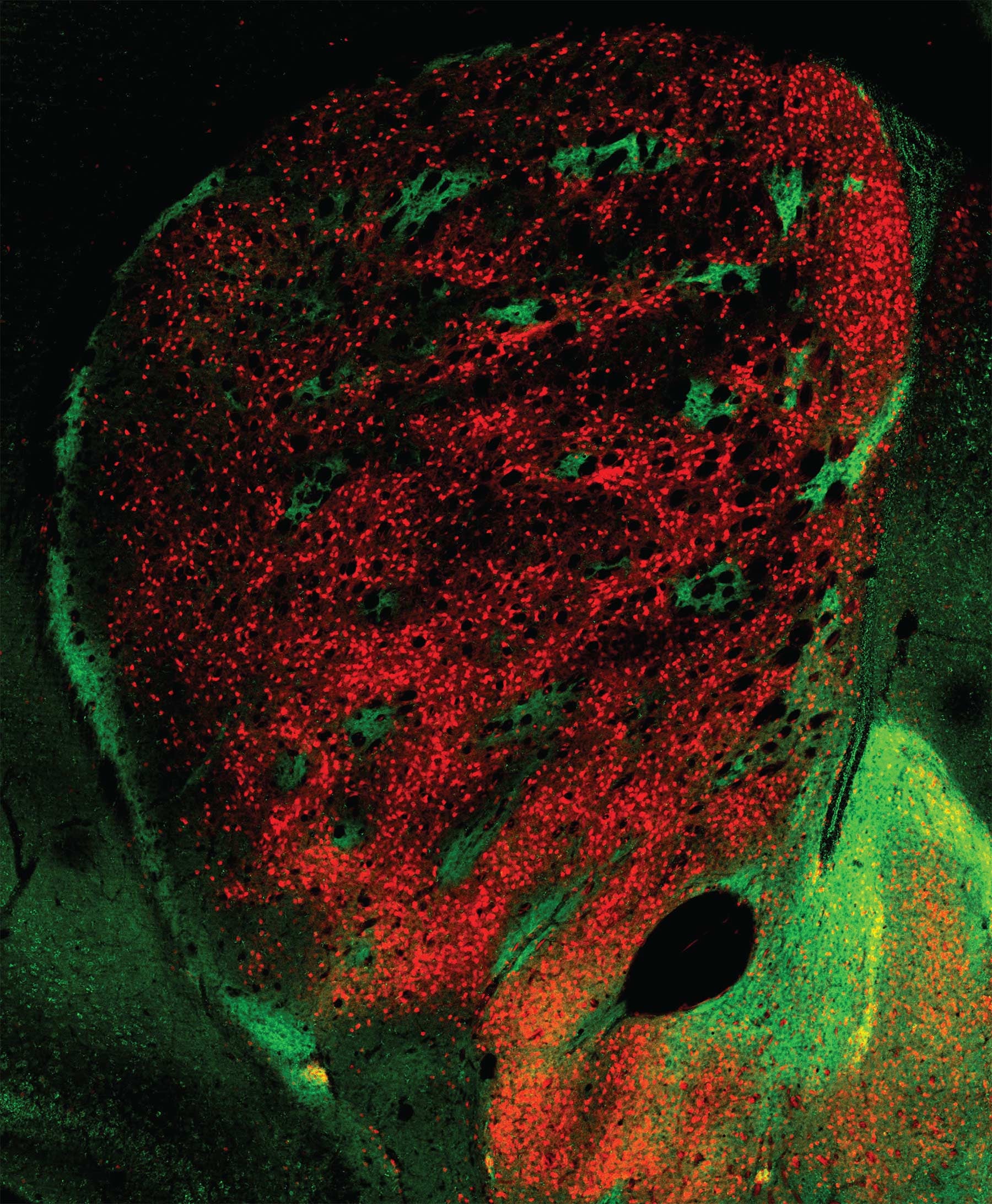

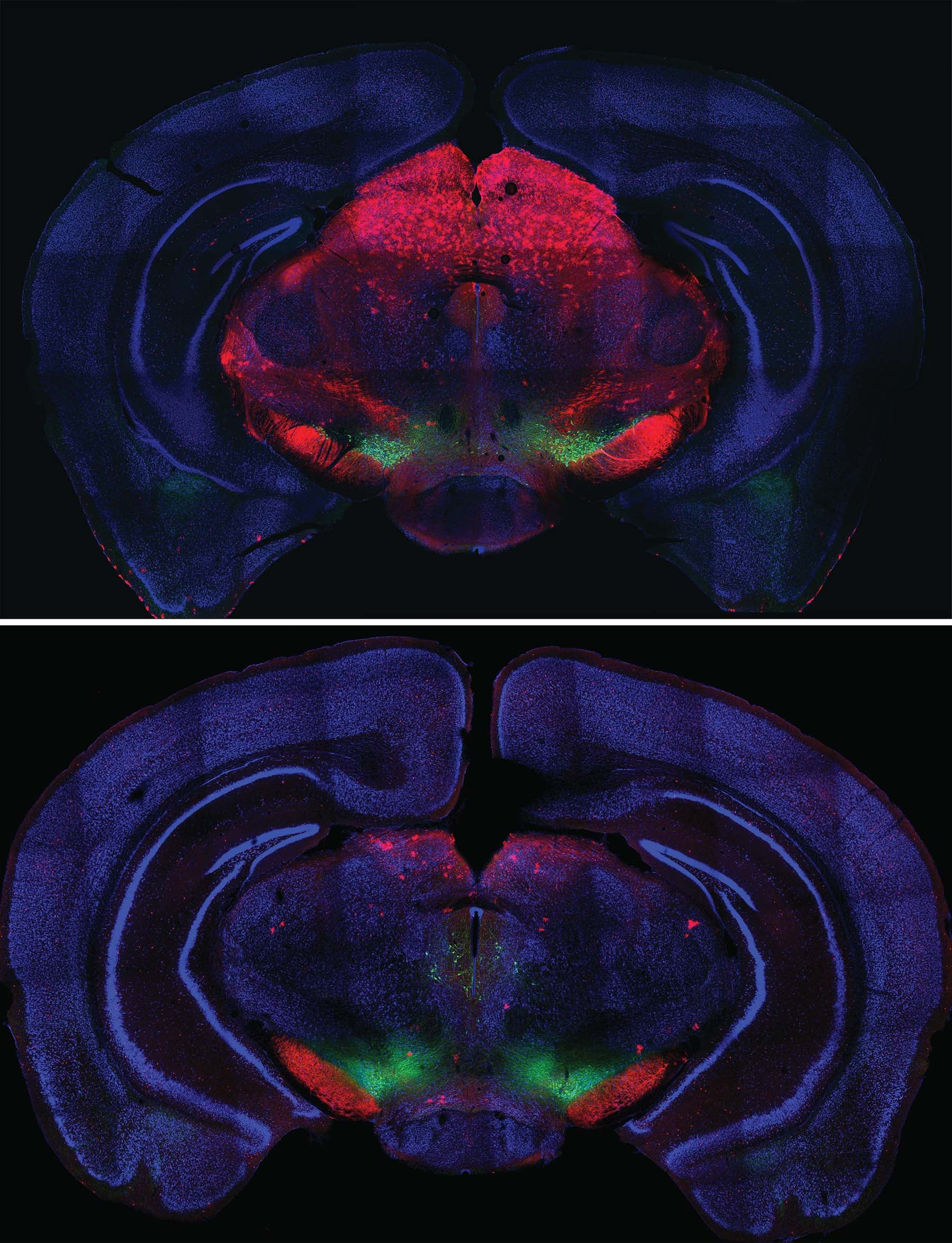

Left: aIPs intermediate precursors generate neurons that assemble to form island-like striosomes in the maturing striatum. Right: bIPs intermediaries generate neurons that form the matrix ‘compartment’ of the striatum.

Striosome ‘islands’ take shape

The matrix materializes

A mysterious finishing touch

The striatum matures

Different connections, different functions

Born of the same cellular “parents,” neurons that form the striosomes and matrix portions of the striatum have different but complementary functions. The two “compartments” develop in parallel, the striosomal “islands” getting a slight head start. Neurons that form them know where to go and how to connect thanks to instructions encoded in genes.

The Huang team’s experiments confirm that the striatum has a second layer of organization that is superimposed over the striosome/matrix organizational plan. Circuits within both striosomes and matrix form two distinct pathways that connect the striatum to other parts of the basal ganglia. In both the striosomes and matrix, one network of neurons forms what neuroscientists call the direct pathway. Signaling within this pathway promotes action. Another network in each compartment, called the indirect pathway, conveys signals that inhibit action. We depend deeply on the proper development and functioning of these interrelated networks. When they are disrupted, for instance in Parkinson’s disease, precision in movements is lost (e.g., difficulty initiating action; shuffling gait) and unwanted movements (e.g., tremor) appear.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455