Team shows how embryonic origin and timing influence cell specification and network integration

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — The cerebral cortex of the human brain has been called “the crowning achievement of evolution.” Ironically, it is so complex that even our greatest minds and most sophisticated science are only now beginning to understand how it organizes itself in early development, and how its many cell types function together as circuits.

A major step toward this great goal in neuroscience has been taken by a team led by Professor Z. Josh Huang, Ph.D., at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). Today they publish research for the first time revealing the birth timing and embryonic origin of a critical class of inhibitory brain cells called chandelier cells, and tracing the specific paths they take during early development into the cerebral cortex of the mouse brain.

These temporal and spatial sequences are regarded by Huang as genetically programmed aspects of brain development, accounting for aspects of the brain that are likely identical in every member of a given species, including humans. Exceptions to these stereotypical patterns include irregularities caused by gene mutations or protein malfunctions, both of which are now being identified in people with developmental disorders and neuropsychiatric illnesses.

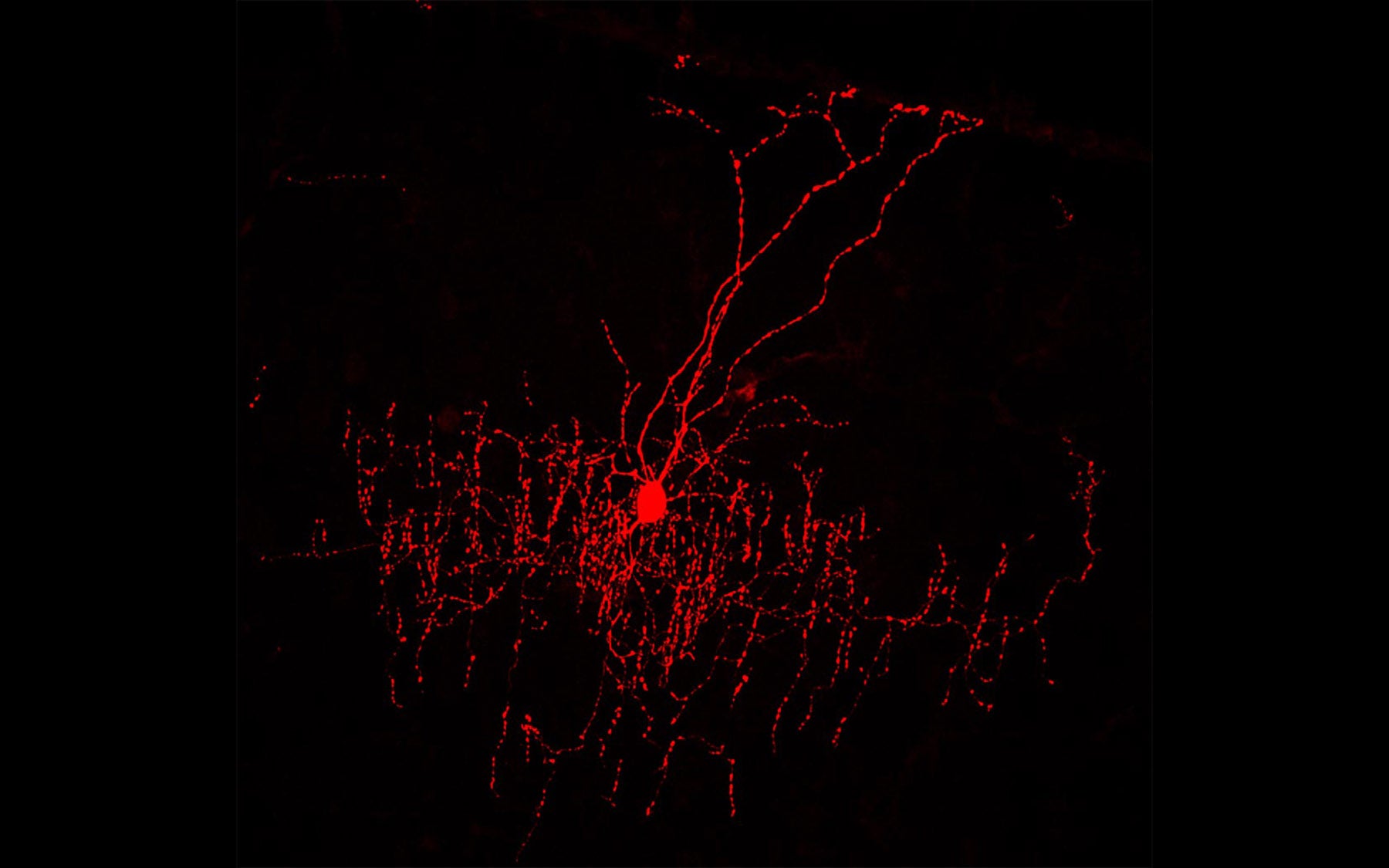

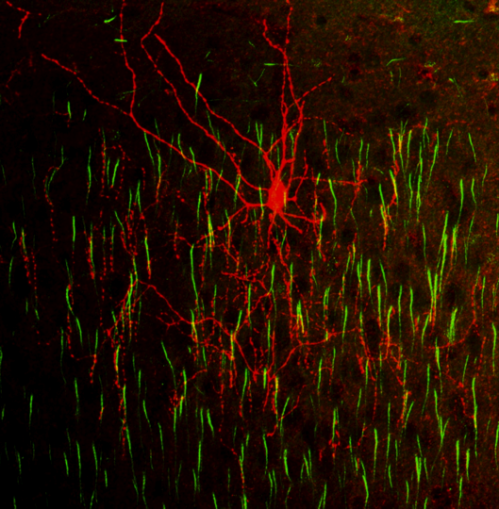

Chandelier cells were first noticed only 40 years ago, and in the intervening years frustratingly little has been learned about them, beyond the fact that they “hang” individually among great crowds of excitatory cells in the cortex called pyramidal neurons, and that their relatively short branches make contact with these excitatory cells. Indeed, a single chandelier cell connects, or “synapses,” with as many as 500 pyramidal neurons. Noting this, the great biologist Francis Crick decades ago speculated that chandelier cells exerted some kind of “veto” power over the messages being exchanged by the much more numerous excitatory cells in their vicinity.

Born in a previously undiscovered ‘country’

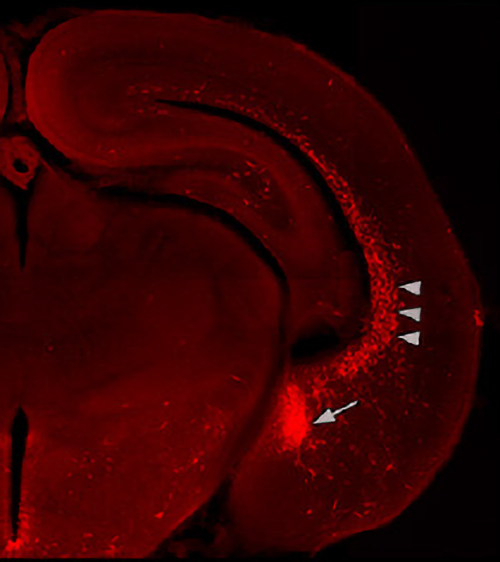

After three years of painstaking work that has involved using new technologies to identify and trace neural cell progenitors in ways not previously possible, and to track them as they migrate to positions in the maturing cortex, Huang and colleagues, including Dr. Hiroki Taniguchi, now at the Max Planck Florida Institute, have demonstrated that chandelier cells are born in a previously unrecognized portion of the embryonic brain, which they have named the VGZ (ventral germinal zone). Chandelier cells are born in a previously undiscovered brain area named by Huang and colleagues the ventral germinal zone (VGZ), indicated in this image with an arrow.

The arrow-heads point to immature chandelier cells migrating from the VGZ toward positions in the mouse cerebral cortex where they will synapse with excitatory cells.

Huang, who has been on a decade-long quest to develop means of learning much more about the cortex’s inhibitory cells (sometimes called “interneurons”), points out that while they are far less numerous than the excitatory pyramidal cells all around them, chandelier cells play an indispensable role in balancing message flow and ultimately in determining the functional organization of excitatory neurons into meaningful groups.

This is all the more intriguing in the case of chandelier cells, Huang explains, because of their distinctive anatomy: one cell that can regulate the messages of 500 others in its vicinity is one that we need to know about if we want to understand how brain circuits work. Unlike other inhibitory cells, chandelier cells are known to connect with excitatory cells at one particular anatomical location, of great significance: a place called the axon initial segment (AIS)—the spot where a “broadcasting” pyramidal cell generates its transmittable message. To be able to interdict 500 “broadcasters” at this point renders a single chandelier cell a very important player in message propagation and coordination within its locality.

Because of the strategic importance of such cells throughout the cortex, it has been a source of frustration to neuroscientists that these and other inhibitory cells have been difficult to classify. Huang has pursued a strategy of following them from their places of birth in the emerging cortex.

Many inhibitory cells come from a large incubator area called the MGE (medial ganglionic eminence). Until now, it was not known that most chandelier cells are not born there, and indeed do not emerge until after the MGE has disappeared. Only at this point does the much smaller VGZ form, providing a place where neural precursor cells specifically give rise to chandelier cells.

The team learned that manufacture of a protein encoded by a gene called Nkx2.1 is among the signals marking the birth of a chandelier cell. The gene’s action, they found, is also necessary to make the cells. Nkx2.1 is a transcription factor, whose expression has previously been linked to the birth of other inhibitory neuronal types. Huang’s team observes that it is the timing of Nkx2.1’s expression in certain precursors—following disappearance of the MGE and appearance of the VGZ—that enabled them to track the birth, specifically, of chandelier cells.

Highly specific migration route and cortical destinations

“In addition to being surprised to discover that chandelier cells are born ‘late’—after other inhibitory cells, in a part of the cortex we didn’t know about,” says Huang, “our second surprise is that once born, these cells take a very stereotyped route into the cortex and assume very specific positions, in three cortical layers.” (Layers 2, 5 and 6). “This leads us to postulate that other specific cortical cell types also have specific migration routes in development.”

As Huang points out, his team’s new discoveries about chandelier cells have implications for disease research, since it is known that the number and connective density of chandelier cells is diminished in schizophrenia. Associations of the same type have recently been made in epilepsy.

“To know the identity of a cell type in the cortex is in effect to know the intrinsic program that distinguishes it from other cell types,” Huang says. “In the broadest terms, we are learning about those aspects of the brain development that make us human. ‘Nurture,’ or experience, also has a very important role in brain development. Our work helps clarify the ‘nature’ part of the nature/nurture mystery that has always fascinated us.”

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 MH094705. Other support came from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, NARSAD/The Brian and Behavior Research Foundation; The Patterson Foundation; The Simons Foundation; The Robertson Neuroscience Fund at CSHL.

Citation

“The spatial and temporal origin of chandelier cells in mouse cortex” appears online ahead of print November 22, 2012 in Science Express. Publication in Science is scheduled for December 14, 2012. The authors are: Hiroki Taniguchi, Jiangteng Lu and Z. Josh Huang. The paper will be available on the Science Express website at 2 pm EST Nov. 22, 2012. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/recent