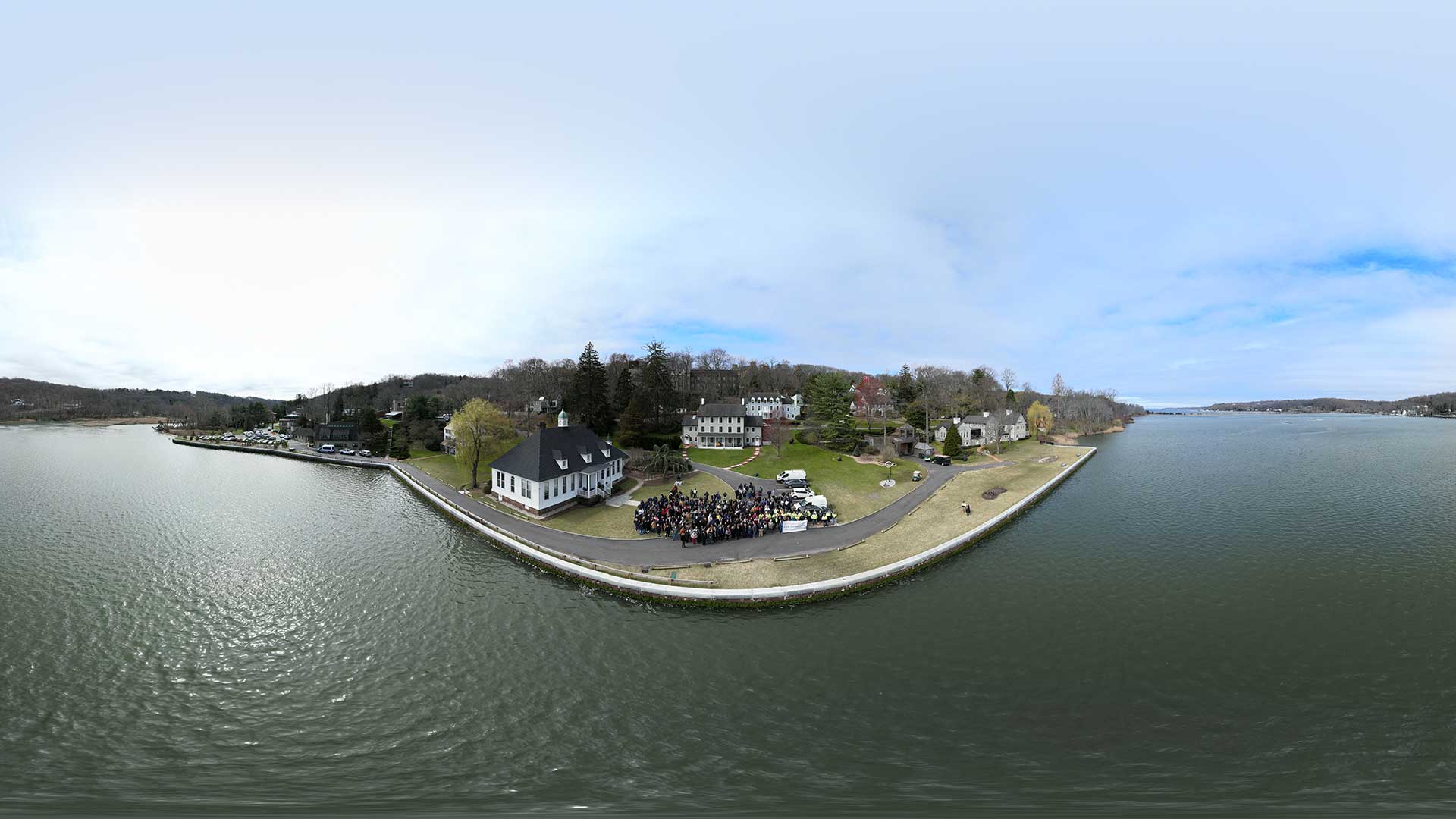

At Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), we deeply value our uniquely vibrant campus and culture. But we thrive because we are intensely engaged with the broad community of scientists across the United States and the world. By collaborating, educating, and sharing knowledge, we amplify our impact, enabling groundbreaking discovery at CSHL and beyond.

This is a precarious moment for the scientific community because science is under threat in the U.S. This country has long led the world in scientific innovation, but cuts to federal funding and restrictive immigration policies threaten to severely limit our progress, stalling vital efforts to improve human health and dampening economic competitiveness.

Investment in basic scientific research—the kind we do at CSHL—fuels innovation, boosts the economy, and paves the way to key medical advances. Discoveries elucidating fundamental mechanisms of biology are the foundation for better treatments, diagnostics, and disease prevention strategies. Studies exploring fundamental biology can take a long time and are typically seen as too risky to be taken on by for-profit pharmaceutical companies, but their findings are crucial starting points for drug development. That means the vast majority of clinical advances can be traced back to work that was done in a publicly funded laboratory.

One recent analysis found that funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) contributed to the development of 100 percent of the new drugs that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved between 2010 and 2016. Another report estimated that every $10 million of NIH funding contributes to 2.3 new private-sector patents. The value of these investments is undeniable from an economic perspective: Every $1 the NIH spends on research leads to $2.46 in economic activity.

The stakes for society

Many of today’s successful treatments have roots in CSHL’s fundamental biology research. This includes medicines now used to treat ER-positive and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer, among other devastating cancers. Importantly, the research that led to these breakthroughs never specifically set out to cure disease; rather, it was fundamental research into how cells control cell division. Nevertheless, the research provided a crucial foundation for future clinical applications. Likewise, our research in plant biology is informing agricultural advancements in the U.S. and abroad, driving our country’s economy, which needs to compete globally. As our focus is on fundamental discovery science, we do not know exactly how today’s discoveries will reshape our well-being in the years to come, but history informs us that basic research is the driver of most innovation, and thus, we must maintain our momentum.

Like most research institutions, CSHL relies on both federal grants and philanthropic donations. Our expenses include the direct costs our scientists need to carry out their individual research programs, as well as research operation costs, such as the operation and maintenance of laboratory infrastructure; research and grant administration; publishing and journal subscription costs; research-specific computing; utilities; and compliance with environmental, health, and safety regulations. Together, direct research project costs and research operation costs account for 86.5% of CSHL’s research budget. The remaining portion of our budget supports general and administrative (G&A) costs, including finance, information technology, human resources, the office of the general counsel, and procurement.

We track these expenditures very carefully, and the funds are not fungible. Unlike a university, we can’t turn to tuition money to support our operational costs. Federal and foundation grants, together with philanthropic donations and our endowment, cover all our research expenses. Any reduction in the grants our investigators receive from federal agencies will diminish the amount and quality of science we are able to do. With fewer resources to support students and postdoctoral fellows, we will also be less able to foster the development of future scientific leaders. The impact would be felt for generations.

The freedom to succeed

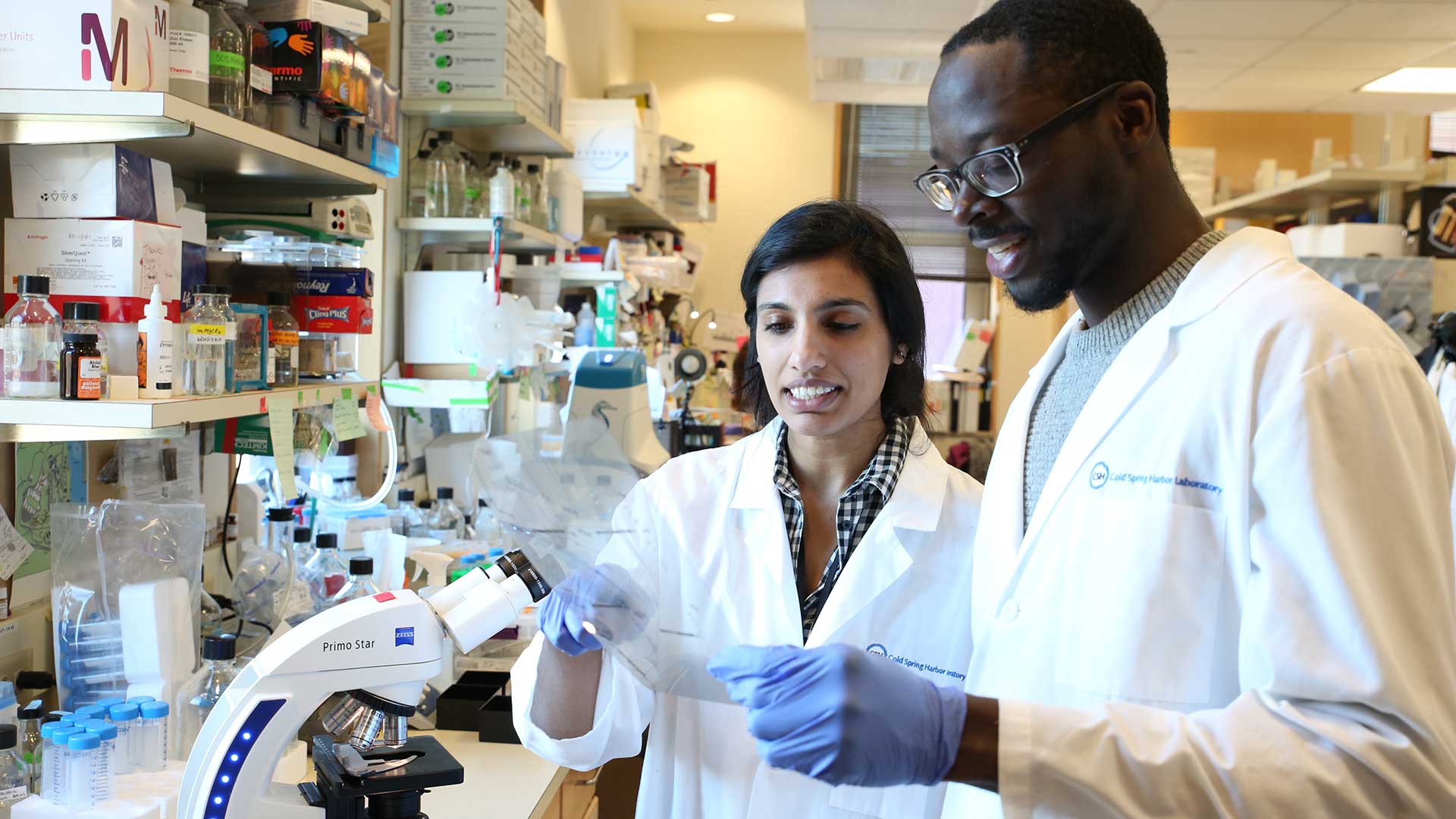

It’s also important to point out, in the face of increasingly restrictive immigration policies, how much we benefit from the bright and diligent scientists who come to the U.S. and do transformative work. Our highly productive research environment and culture of intellectual freedom have long drawn scientists from around the world to the U.S. Many of those individuals found few opportunities in their own countries but excelled here.

Approximately 35 percent of the Americans who have won Nobel Prizes in chemistry, medicine, and physics since 1901 were immigrants. That includes Richard Roberts, a former CSHL scientist from the United Kingdom whose discovery that genes can be encoded in discontinuous segments of DNA opened the door to a new understanding of how genetic information is used by cells, with implications for many kinds of disease. Spinraza®, a revolutionary treatment developed by another immigrant to the U.S., CSHL molecular biologist Adrian Krainer, for the pediatric neurodegenerative disorder spinal muscular atrophy, is just one of the many successes made possible by Roberts’ work and that of his colleagues.

On a personal note, immigrating to the U.S. was pivotal for my own career. In 1979, I came to CSHL from Australia, eager to investigate how our genome is inherited and how this fundamental process is regulated. The U.S. was the obvious place to be for a young scientist like me. It’s where all the cutting-edge research was being done. Once I started at CSHL, I had more freedom to follow my ideas than I would have had at most other places. So, I was able to make substantial contributions to my field.

Today, CSHL remains committed to empowering early-career scientists, wherever they come from. But the landscape has changed. There are more opportunities now to do science in other parts of the world, making it all the more important that our country maintains a supportive culture that attracts talented scientists to U.S. laboratories and lets new ideas flourish.

The future of our country

At the same time that scientists and scientific institutions are threatened, we are also seeing increasing efforts to discredit science among the public. This has fueled an alarming rise in vaccine skepticism, which has already led to an outbreak of measles spreading through the U.S. starting in early 2025. Declining vaccination rates will exacerbate the situation and put people at risk for other illnesses that are easily avoidable.

This is one reason our DNA Learning Center (DNALC), whose programs reach 30,000 precollege students every year just on Long Island, is so important. A primary goal of the DNALC has always been to educate the public about biology and genetics so they can make informed decisions about their personal health. By engaging students in hands-on science, we help equip them to think critically in the face of increasing misinformation and disinformation campaigns.

We have been expanding the DNALC, with new facilities opened in New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and Nigeria over the last five years. Licensing the DNALC teaching model further expands our reach, bringing modern biology to students across the U.S. and in cities around the world. With anti-science rhetoric on the rise in the U.S., these educational efforts remain a high priority for CSHL. As our licensing program grows, we would like to see schools in more rural or under-resourced areas adopt this powerful approach to science education. Toward this end, we are collaborating with Regeneron to establish a DNALC in Nashville, Tennessee, at Meharry Medical College—part of a broader middle and high school education initiative in the historic southern city.

A beacon of truth and hope

One bright light for the future is the strong philanthropic support for science in the U.S. Private philanthropists cannot and should not be expected to uphold the position of the U.S. as a worldwide leader in science and innovation. However, generous donations from organizations and individuals have always helped drive the most innovative research at CSHL. For that, we are enormously grateful. Such support will be especially vital in the coming years, as scientists at CSHL and beyond renew their commitment to expanding the frontiers of biology and making life better for everyone.

As I write this essay in the spring of 2025, CSHL has already made great strides in getting our message out among policymakers, their financial backers, and the general public. Here in New York and nationwide, we will continue to take a leading role in promoting the critical need for public research funding. A lot can change between now and next year. But no matter what happens, fundamental biology remains crucial for science and society.

—Bruce Stillman, Ph.D.

“President’s message”

CSHL 2024 Annual Report