Over 670,000 high school students learned hands on genetics at the DNA Learning Center; in 2019, 67,550 used PCR, the technology at the heart of COVID-19 testing. Here is a chance to catch up with what those students know.

The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) DNA Learning Center (DNALC) has taught over 670,000 students and teachers hands-on genetic techniques with the goal of preparing them for life in this genome age. Good thing, because with SARS CoV-2 coronavirus (the causative agent of COVID-19) spreading around the world, knowledge about genetic techniques like PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) is especially useful. Hospitals and clinics are trying to implement patient testing as fast as they can and clinicians are using a type of PCR technique called rtPCR to find traces of the virus’s genome in patient samples.

What is PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction)?

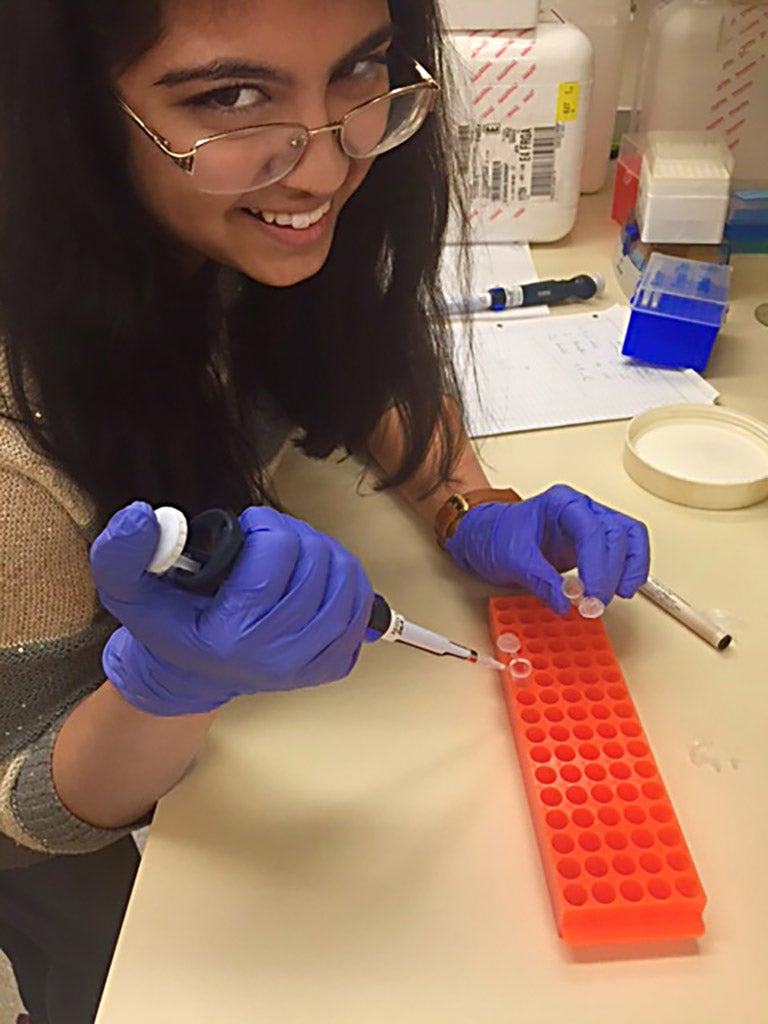

One of those students is Tamanna Bhatia. In high school, she attended classes and did research at the DNALC. She studied versions of a gene that protects people from getting cancer. “We’re using a technology called PCR, which I’d never heard of before,” she said. “With PCR, I can replicate a single molecule of DNA many times so that it is easier to see.”

There are four main steps to doing PCR. In the first step, double stranded DNA is heated nearly to boiling to separate the two strands. When the DNA is cooled a little, a small stretch of DNA that includes the gene of interest, say coronavirus sequence, binds to a complementary sequence on the long strand of DNA. Cool down the mix a little more, and a DNA polymerase enzyme builds long strands of DNA. One copy of the target sequence becomes two. Then the whole cycle of steps is repeated. Two copies become four. Four become eight. The number of copies of the target sequence grows exponentially until it reaches a level that can be detected.

According to Micklos, “We pioneered methods and educational kits to allow students to look at their own DNA using PCR. So we have helped create several generations of students and teachers who have a basic understanding of how the test for the presence of coronaviruses works. This is how lab science supports informed public participation in health care.”

Since 1988, 670,000 high school students have learned hands-on genetics techniques at the DNALC. And though coronavirus is what is in the news now, PCR technology has broad applications to understanding species diversity, cancer, and evolution.

What is the rtPCR test for coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses—tiny bubbles of grease and protein surrounding a core of RNA. The first step is to break open the bubble and unroll the long, fragile single-stranded RNA inside. Then add a viral enzyme that transcribes (copies) the RNA into DNA. The enzyme is called reverse transcriptase because animal cells normally transcribe DNA into RNA. But RNA viruses (including coronavirus, HIV, and others) need to make double stranded DNA copies to get an infected cell to make viral proteins. They package a reverse transcriptase into each viral particle. Once the RNA is read and a stable, double stranded DNA copy is made, the cell can make viral proteins. Tests for RNA viruses need to replicate that natural step before PCR can begin.

For animations and videos on PCR from the DNA Learning Center, check out the following educational resources:

- This 3D animation describes all 4 PCR steps.

- In this interactive animation you can go through each step for many cycles and watch the target sequence accumulate.

- And here is the inventor of PCR, Kary Mullis, describing the technique and the admittedly unexciting way he named his Nobel Prize winning technique.

Written by: Eliene Augenbraun, Creative Director | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455