Base Pairs podcast

One day, while out tending their experimental tomato fields, Associate Professor Zachary Lippman and his team found something totally bizarre and common at the same time. It was a tomato that looked like a baby, with a head, a body, and arms that seemed to be waving “hello”—and it wasn’t some laboratory-created mutant.

In this chat episode, we talk about the parts of our interview with Lippman that didn’t make it into the full episode, “CRISPR vs. climate change,” and learn that “what’s wonderful about genetics is that you see crazy stuff all the time.” Lippman and his team grow thousands of plants each year for their research, many of which are tomatoes, but some are close relatives of tomatoes. Base Pairs producer Brian Stallard’s mind was blown when he heard what else is in the tomato family, and how Lippman Lab has fun with some of these tomato relatives.

AA: And I’m Andrea.

BS: This is our second chat episode of Base Pairs. We kind of make these episodes so you can get sort of a backstage pass into what’s going on here at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and a little bit of off the cuff discussions that happened in our previous episode. Last episode was CRISPR versus Climate Change, and Andrea had talked to associate professor Zach Lippman. He’s a plant scientist here at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Andrea, what did you guys talk about?

AA: Yeah. What we talked about in the episode was mostly what Zach does in the lab. He is using techniques like CRISPR, this new genome editing tool to make precise changes in the genomes of tomatoes. The plant that he focuses. But I also wants to talk to him about the other big part of his work, which is going out in the field, and growing tomatoes basically the same way a farmer would. I wanted to know about what kind of the weirdest things he’s found out there have been.

ZL: Yeah. What’s wonderful about genetics is that you see crazy stuff all the time. We’ve seen tomato plants that instead of making clusters of flowers, we’ll make the equivalent of cauliflower. It’ll just massively over proliferate what are called meristems. This is where stem cells are in plants, and you’ll got to the plant, and you won’t see during the peak of flowering, you won’t see one yellow flower. All you’ll see are these giant clusters of branched cauliflower. That’s one really crazy mutant that we worked on in the past, and as you might imagine the gene that was no longer working in that plant, or was mutated was responsible for making flowers. This is why you end up with this cauliflower type trait because it’s not able to make flowers.

We’ve seen plants that will instead of making nice round fruits, we’ll make these crazy shapes of fruits, which of course many different people who’ve grown tomato before. Heirloom tomatoes will have seen these types of shapes, but we’re sometimes finding even crazier shapes. Things that we look at and were quite clear in our minds that it would have no business being grown for consumption because it looks so weird. Sometimes we get fruits that have appendages, and it’s not because of any weird laboratory based experiments that we’re doing, this happens naturally. I mean you can see this in many different plants, and many different types of fruit bearing plants where you’ll have a tomato that will have what looks like a nose coming out of it, or arms and legs. In fact last year we had one that looked like a little baby. Two arms, two legs, and a belly. This happens sometimes.

AA: Did anybody eat it?

ZL: No, but they drew a face on it, and a belly button, and we took a nice picture of it, and sometimes we show it in presentations.

AA: I want to see that picture.

ZL: Yeah. I can show it to you sometime. It’s really funny. We see all sorts of crazy things when you do genetics. I think what’s most exciting is that not so much the weirdness, but what the weirdness is going to tell you once you start to understand why it’s weird, and this is really the secrets of genetics.

BS: Wait, so did Zach deliver on this promise that he made? Do we have the photos of tomato baby? Now you’ve piqued my interest.

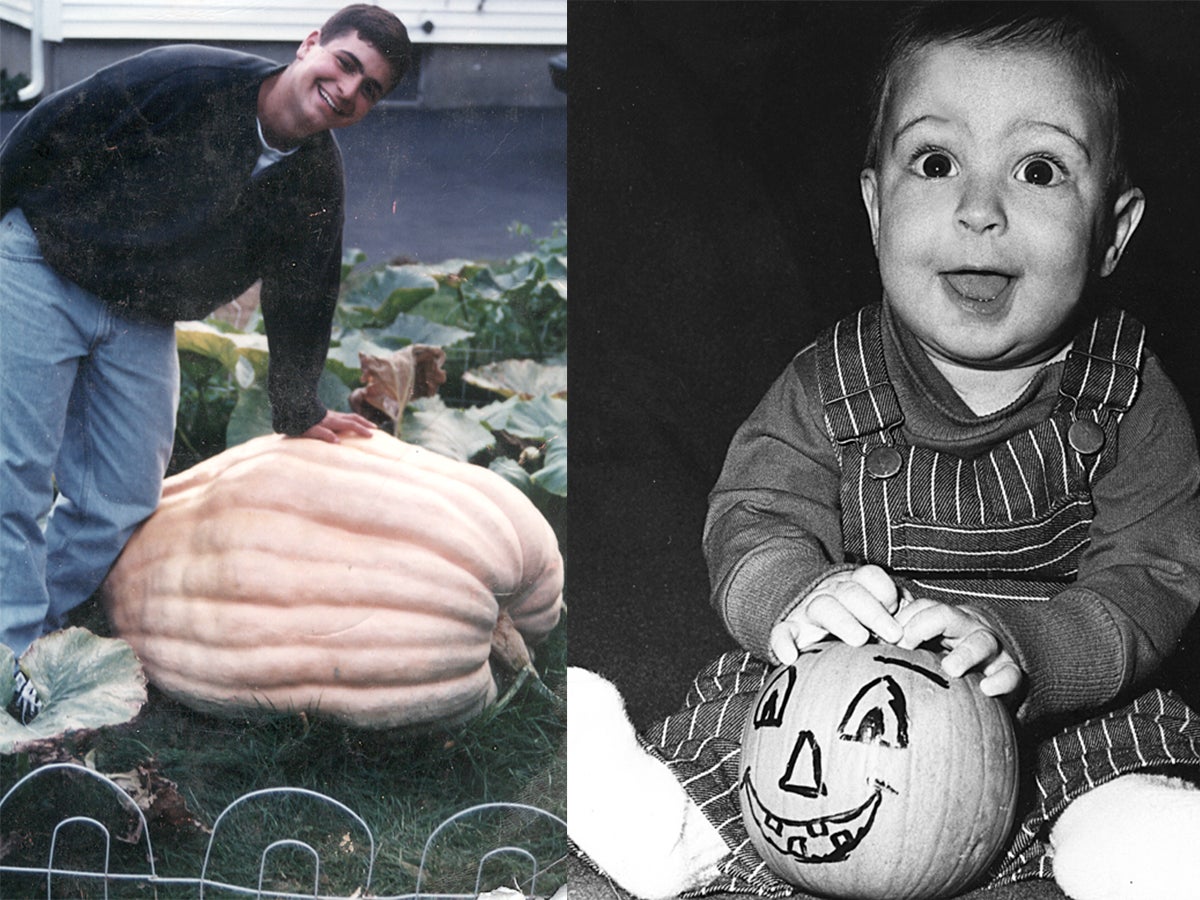

AA: He did indeed. He delivered on the tomato baby photo, and on other baby photos. Specifically Zach Lippman baby photos. You should definitely also check out, and it is posted on our lab dish blog for all of you to see. In one of those photos you’ll see baby Zach in his little overalls with a pumpkin, which I found out also has a lot of significance to him. He had said in the last episode. I was surprised to learn that even though he studies tomatoes, he really strongly disliked tomatoes growing up.

BS: I think the word was despised.

AA: Yes. But he felt very differently about pumpkins, and he’ll tell you a little more about that in this clip.

ZL: We often grow a few crops on the side, and one of the most special ones to my heart has been growing giant pumpkins, which I have been doing for many years, and the idea is to get it as big as we can every year, and we do not too bad. We’re not near the top where some of the largest pumpkins have broken 2000 pounds, but we get up there in the several hundred.

BS: Aha! Now everything makes sense. All over our campus every October season, suddenly massive pumpkins pop up, and I kind of never knew how they got there.

AA: Yeah. Pretty massive. I took a photo once. The pumpkins were on campus for Instagram, and I felt that I needed to put a small child in the photo for scale, so you could tell that this pumpkin was several times larger than this toddler. That’s really just a fun project that Lippman Lab tends to while they’re in the fields for the summer growing their tomatoes. But they also have another side project that is a little bit more relevant because tomatoes are part of a family of plants that has some members that you’re already are familiar with like potatoes, eggplants.

BS: Stop. Explain to me how a potato is related to a tomato?

AA: Not only are potatoes are related to tomatoes, but tobacco is in that family.

BS: What? Wait, what is the family?

AA: It’s called the Nightshade family.

BS: The Nightshade family.

AA: Also known as Solanaceae.

BS: This is nightshade. You make poison from nightshade? The infamous nightshade?

AA: Yes. Indeed.

BS: Oh wow. The things we learn in Base Pairs.

AA: Yeah.

BS: Okay. What is this other mysterious plant?

AA: The other plant in this family that Zach’s lab is really interested in is peppers. They’re interested because they’re related to tomatoes, but what they’re also interested in is that some of those peppers are very, very spicy.

ZL: The side project is that we work on pepper. Pepper is a very closely related relative of tomato in the Solanaceae family. There are many attributes of pepper that are similar to tomato, and we have a very large project to study flower production in pepper because unlike tomato where every cluster of flowers will be anywhere from 7 to 15 flowers. That translates to 7 to 15 fruits on the tomatoes on the vine. Pepper plants typically will make one flower in every “cluster”. We’re very interested in the few wild species of pepper, wild relatives of pepper that will make a few more flowers. Sometimes three to four flowers in each cluster. We have a large project. Now, the reason that sort of somewhat of a hobby on the side is that a lot of these peppers are extraordinarily spicy, and people in the lab every summer will collect from the spiciest varieties, and there’ll be taunting in the lab, and competitions about who’s willing to pop one of those peppers, and maintain a straight face. At least for a minute or two, yeah.

I’ve heard that people have taken some of the hottest peppers. The Reaper for example, or the Ghost Pepper, and made at home these extraordinarily hot sauces. These salsa type sauces that will last in the lab for up to a year because you only need a drop or two in order to spice up food.

AA: Oh my.

ZL: Yeah. The pepper project is a fun one that has real, real value to. Actually, our entire research program.

AA: I heard around campus that… We have a bar on campus, and I had heard that at the end of the summer, Lippman lab would all go down to the bar with a bunch of jars of different kinds of peppers, and they would play Russian Roulette with tasting the peppers, and you would have to try to withstand it for as long as you can, and they would make this kind of drinking game out of it.

BS: I don’t know. I think I can handle this. I got to go find Zach and get in on this game here.

AA: We’ll see.

BS: Very cool. That’s it. That’s everything that we have?

AA: Yeah, that does it for this time. Definitely make sure that you go to our LabDish blog. See all the great photos of bizarre tomatoes, and baby Zach, and giant pumpkins, and all the fun things that go on in Lippman Lab.

BS: Right. Next month we’ve got another full story episode, so we’ll dive right back into the science that goes on here, and the implications in real life, and the power of genetic information as this podcast is all about. Thanks for tuning in guys.

AA: Thanks. We look forward to talking to you next time.

BS: Yeah. Bye everybody.

Extras for Episode 10.5

Before Lippman was the head of a laboratory that focuses on tomatoes, one might have guessed that he would end up studying pumpkins. He started growing giant pumpkins as a kid, and still keeps that hobby up today.

Over the years, Lippman has seen countless oddities growing in his experimental fields that arose completely naturally. As a plant geneticist, he enjoys trying to understand the genetic factors that cause these strange traits.

Written by: Andrea Alfano, Content Developer/Communicator | webservices@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455