Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Using a revolutionary new brain-mapping technology recently developed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), an international team of scientists led by Professor Anthony Zador have made a discovery that will force neuroscientists to rethink how areas of the cortex communicate with one another.

The new technology, called MAPseq, allowed the scientists to determine that neurons in the primary visual cortex communicate with higher visual areas of the cortex much more broadly than previously believed, and according to specific patterns.

The wiring diagram of the cortex determines how information is processed across dozens of cortical areas. “If we don’t know how information is combined even at the earliest stages, then we have essentially no shot of figuring out how the brain works,” says Justus Kebschull, now a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University who was instrumental in developing MAPseq as a graduate student in Zador’s lab.

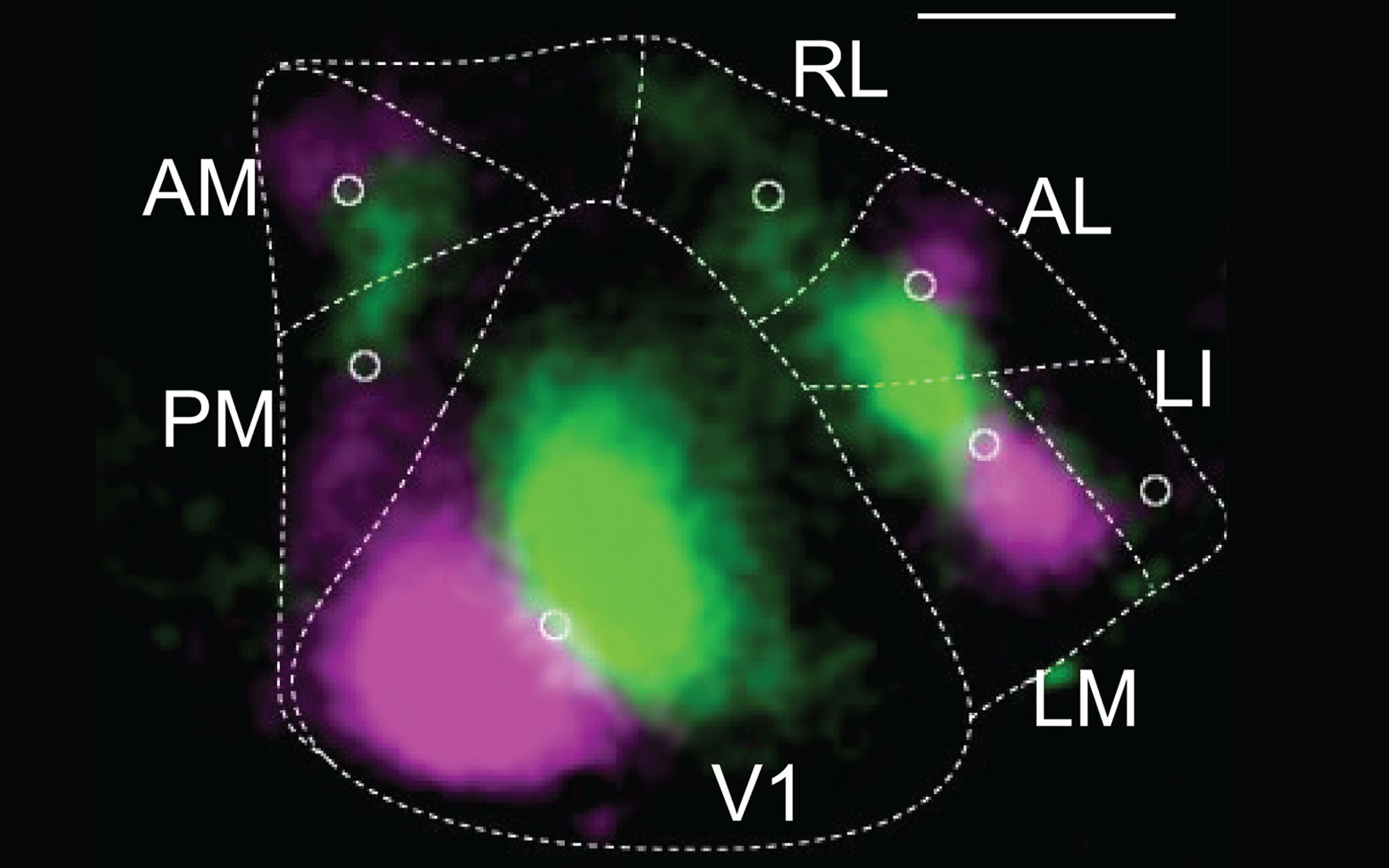

In a MAPseq experiment, hundreds or thousands of neurons are labeled uniquely with random RNA sequences (“barcodes”) via a single injection made in the brain. The barcodes are transported into the branching axons of each labeled neuron, where they can later be read out by high-throughput barcode sequencing after the brain is dissected. This process allows researchers to identify every brain area that each barcoded neuron makes contact with.

The Zador lab has begun to use MAPseq to compare the brains of a mouse autism model with healthy mouse brains to see if mis-wiring occurs during development at the single-neuron level that might explain the disorder’s symptoms—just one of many potential applications of the method.

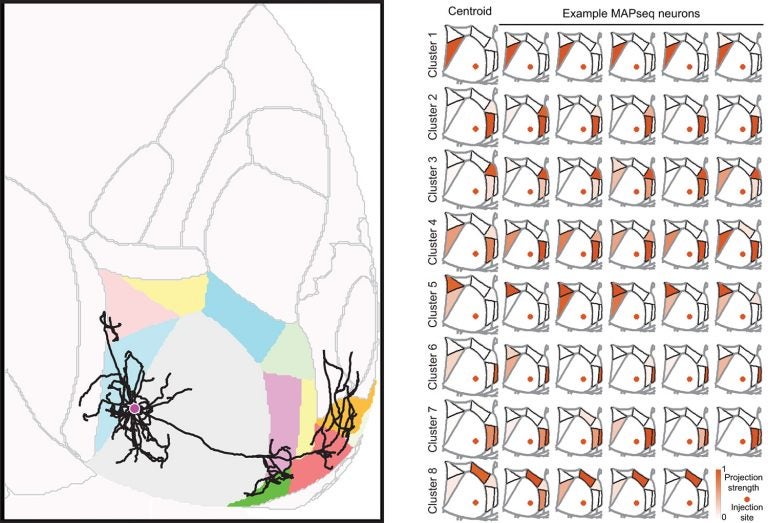

In the experiments reported today, the team first verified the relatively new technology by comparing its results with the gold-standard mapping method, called single-neuron tracing. They used the latter method to trace 31 mouse neurons in the primary visual cortex to up to seven different cortical locations. These experiments took 3 years to complete. It then took them only 3 weeks to use MAPseq to map the projections within the cortex arising from 591 primary visual cortex neurons. Both techniques revealed that the majority of neurons in this location target multiple visual areas, and that roughly the same proportions of cells project to two, three, or four cortical areas.

Beyond just being faster, MAPseq was able to reveal patterns in the way that neurons in the primary visual cortex connected to other visual areas across the cortex. About 73% fit into one of six distinct projection patterns. This architecture may facilitate coordination of activity among those areas, which in turn could provide a means of linking visual information across the brain to help form complex percepts.

“Our finding signals a shift away from the rather convenient idea of every neuron projecting to just one cortical area,” says Kebschull. “That thinking ignores the underlying structure of the brain, and in the future, the way people do their experiments is going to change drastically.”

Written by: Chris Palmer, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

U.S. National Institutes of Health; Brain Research Foundation; IARPA (MICrONS); Simons Foundation; Paul Allen Distinguished Investigator Award; Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds; Genentech Foundation; European Research Council; Swiss National Science Foundation.

Citation

Han Y et al, “The logic of single-cell projections from visual cortex,” appears online March 28, 2018 in Nature.

Principal Investigator

Anthony Zador

Professor

The Alle Davis and Maxine Harrison Professor of Neurosciences

M.D., Ph.D., Yale University, 1994