A team of plant geneticists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has successfully demonstrated what it describes as a “simple hypothesis” for making significant increases in yields for the maize plant.

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — A team of plant geneticists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has successfully demonstrated what it describes as a “simple hypothesis” for making significant increases in yields for the maize plant.

Called corn by most people in North America, modern variants of the Zea mays plant are among the indispensable food crops that feed billions of the planet’s people. As global population soars beyond 6 billion and heads for an estimated 8 to 9 billion by mid-century, efforts to boost yields of essential food crops takes on ever greater potential significance.

The new findings obtained by CSHL Professor David Jackson and colleagues, published online today in Nature Genetics, represent the culmination of over a decade of research and creative thinking on how to perform genetic manipulations in maize that will have the effect of increasing the number of its seeds—which most of us call kernels.

Plant growth and development depend on structures called meristems—reservoirs in plants that consist of the plant version of stem cells. When prompted by genetic signals, cells in the meristem develop into the plant’s organs—leaves and flowers, for instance. Jackson’s team has taken an interest in how quantitative variation in the pathways that regulate plant stem cells contribute to a plant’s growth and yield.

In less than a minute: CSHL Prof. Dave Jackson on new genetic method to boost corn yield

“Our simple hypothesis was that an increase in the size of the inflorescence meristem—the stem-cell reservoir that gives rise to flowers and ultimately, after pollination, seeds—will provide more physical space for the development of the structures that mature into kernels.”

Dr. Peter Bommert, a former postdoctoral fellow in the Jackson lab, performed an analytical technique on several maize variants that revealed what scientists call quantitative trait loci (QTLs): places along the chromosomes that “map” to specific complex traits such as yield. The analysis pointed to a gene that Jackson has been interested in since 2001, when he was first to clone it: a maize gene called FASCIATED EAR2 (FEA2).

Not long after cloning the gene, Jackson had a group of gifted Long Island high school students, part of a program called Partners for the Future, perform an analysis of literally thousands of maize ears. Their task was to meticulously count the number of rows of kernels on each ear. It was part of a research project that won the youths honors in the Intel Science competition. Jackson, meantime, gained important data that now has come to full fruition.

The lab’s current research has now shown that by producing a weaker-than-normal version of the FEA2 gene—one whose protein is mutated but still partly functional—it is possible, as Jackson postulated, to increase meristem size, and in so doing, get a maize plant to produce ears with more rows and more kernels.

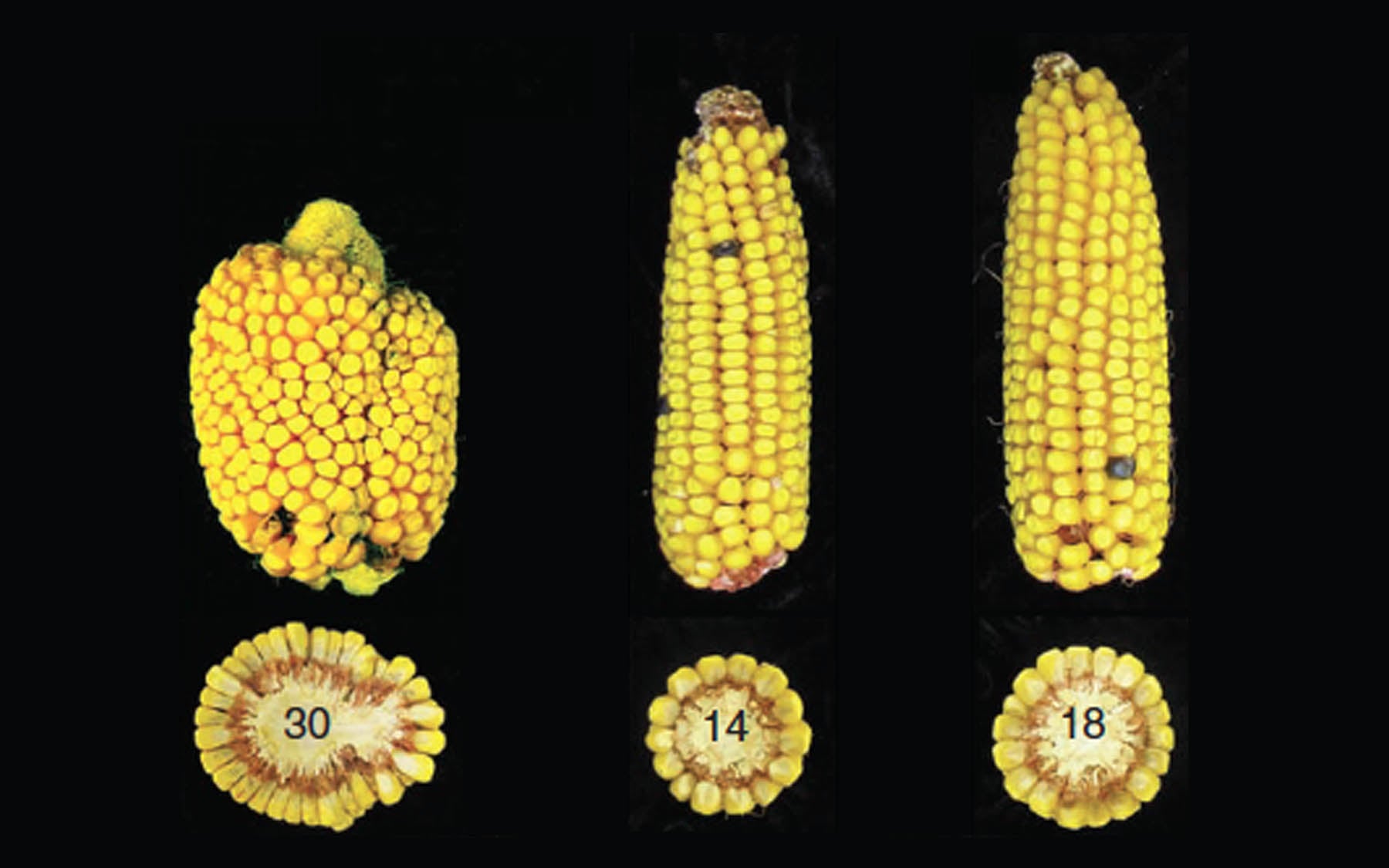

How many more? In two different crops of maize variants that the Jackson team grew in two locations, with weakened versions of FEA2, the average ear had 18 to 20 rows and up to 289 kernels—as compared with wild-type versions of the same varieties, with 14 to 16 rows and 256 kernels. Compared with the latter figure, the successful FEA2 mutants had a kernel yield increase of some 13%.

“We were excited to note this increase was accomplished without reducing the length of the ears or causing fasciation—a deformation that tends to flatten the ears,” Jackson says. Both of those characteristics, which can sharply lower yield, are prominent when FEA2 is completely missing, as the team’s experiments also demonstrated.

Teosinte, the humble wild weed that Mesoamericans began to modify about 7000 years ago, beginning a process that resulted in the domestication of maize, makes only 2 rows of kernels; elite modern varieties of the plant can produce as many as 20.

A next step in the research is to cross-breed the “weak” FEA2 gene variant, or allele, associated with higher kernel yield with the best maize lines used in today’s food crops to ask if it will produce a higher-yield plant.

Such work can now be carried out by DuPont-Pioneer, a seed company that helps support and shares in the fruits of leading-edge plant research at CSHL in order to discover and develop new varieties to meet the world’s growing food needs.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

The research described in this release was supported in part by funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (grant NRICGP 2003-3504-13277); the National Science Foundation Plant Genome Program (grant DBI-0604923); and the German Science Society.

Citation

“Quantitative variation in maize kernel row number is controlled by the FASCIATED EAR2 locus” appears online in Nature Genetics on February 3, 2013. The authors are: Peter Bommert, Namiko Satoh Nagasawa and David Jackson. The paper can be viewed at: http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/vaop/ncurrent/index.html