Braking signals from the leaves tell stem cells to stop proliferating

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Biologists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have made an important discovery that helps explain how plants regulate the proliferation of their stem cells. The discovery has near-term implications for increasing the yield of maize and many other staple crops, perhaps by as much as 50%.

The newly discovered regulatory pathway, reported today in Nature Genetics, is notable in that it channels signals emanating from a plant’s extremities—emerging young leaves called primordia—to the stem cell niche, called the meristem, located at the plant’s growing tip.

Plant biologists have long known of another pathway, called the CLAVATA-WUSCHEL pathway, that regulates stem cell proliferation from within a portion of the meristem itself, called the organizing center (OC). In this canonical pathway, “the receptor and ligand are [both] expressed in the stem cells, which send signals down to the cells just below, in the OC,” explains CSHL Professor David Jackson, who led the team that found the new pathway.

WUSCHEL is a transcription factor that alters gene expression, and in so doing promotes the proliferation of stem cells, which are totipotent—capable in plants, as in humans, of developing into cells of any type. In the canonical CLAVATA-WUSCHEL pathway, stem cells send back to the OC a negative signal, repressing the signal for proliferation.

A similar feedback is established in the newly discovered pathway, although its signal begins in leaves. Having a signal coming from the leaves is new, and exciting because it could act as a kind of environmental sensor, telling totipotent stem cells in the meristem to stop proliferating—a brake, applied from the older, more developed parts of the plant, for example in response to environmental cues such as available light, nutrients or moisture.

Jackson and colleagues identified the receptor for these “braking signals from the leaves” in cells in the lower part of the meristem. They named the receptor FEA3. They also discovered the ligand that interacts with the receptor, a protein fragment called FCP1.

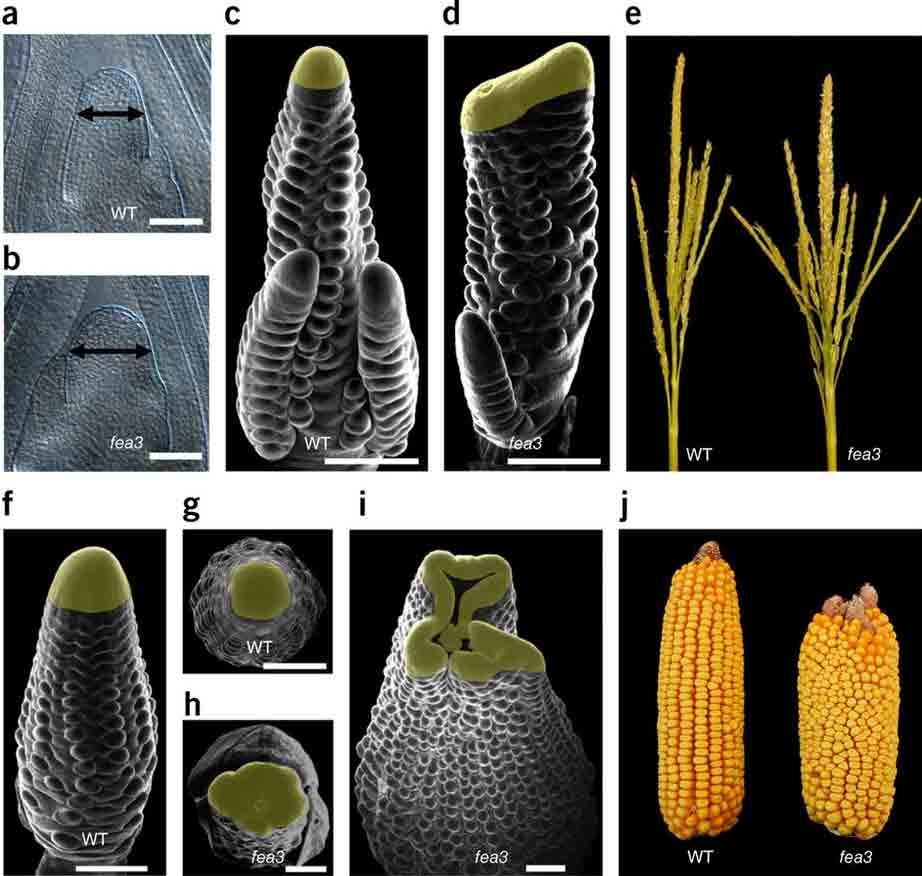

When FEA3 receptors in the meristem are not able to function at all, “it is as if they are blind to FCP1,” says Jackson. The inhibitory signal FCP1 sends from the leaves to the meristem is not received, and stem cells proliferate wildly. The plant makes far too many stem cells, and they give rise to too many new seeds—seeds the plant cannot support with available resources (light, moisture, nutrients). In such FEA3 mutant plants, maize ears develop that exhibit a quality called fasciation; from their greatly extended meristems, too many baby kernels are generated, which form misshapen, and ultimately yield-poor ears.

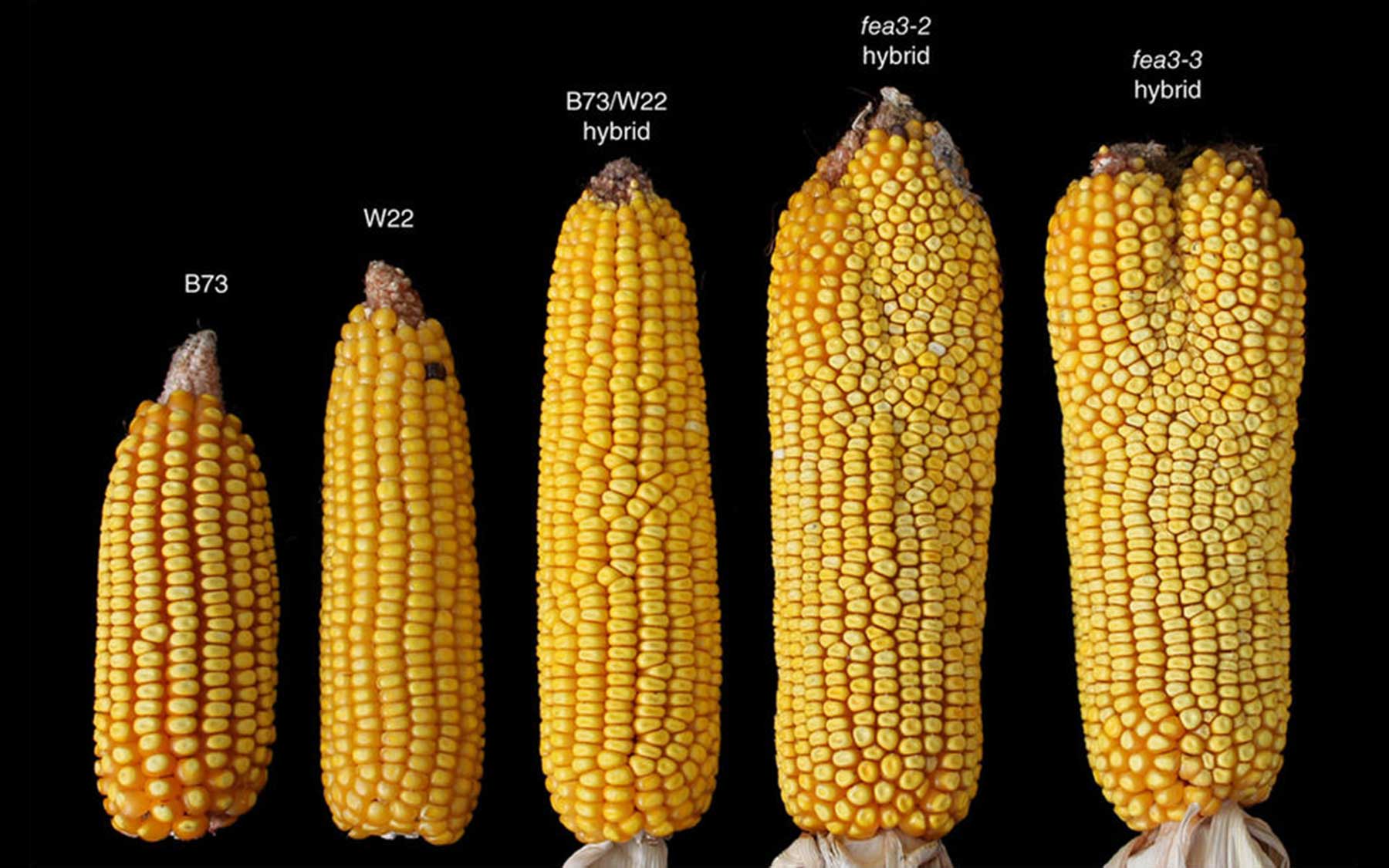

But when Jackson’s team performed a genetic trick, growing plants with so called “weak alleles” of the FEA3 gene, function of the FEA3 receptor was only mildly impaired. This moderate failure of the braking signal from outside of the meristem gave rise to a modest, manageable increase in stem cells, and to ears that were significantly larger than ears in wild-type plants.

These ears, the product of maize plants grown from weak alleles of FEA3, had more rows of kernels, and up to 50% higher yield overall than wild-type plants.

Because the newly discovered FAE3-FCP1 pathway is highly conserved across the plant kingdom, the discovery by Jackson’s team holds the prospect of translating into significant increases in yield in all the major staple crops.

Before such translational work can proceed, Jackson and colleagues plan to test the newly discovered fea3 alleles in elite varieties of maize and other crops in agricultural trials.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This research was supported by: Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI), National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), USDA, NSF Plant Genome Research Program; Dupont Pioneer; the Gatsby Charitable Foundation; Swedish Research Council; Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Citation

“Signaling from organ primordial regulates stem cell proliferation and maize yields, via the FASCIATED EAR3 receptor-like protein” appears online in Nature Genetics on Monday, May 16, 2016. The authors are: Byoung Il Je, Jeremy Gruel, Young Koung Lee, Peter Bommert, Edgar Demesa Arevalo, Andrea L. Eveland, Qingyu Wu, Alexander Goldshmidt, Robert Meeley, Madelaine Bartlett, Mai Komatsu, Hajime Sakai, Henrik Jönsson and David Jackson. The paper can be obtained at: http://www.nature.com/ng/index.html