Penicillin changed the world. The drug turned infections that had threatened lives into something that could be cured with a shot. But there was a catch. It only worked if you could get it and distribute it. During World War II, the U.S. military could not. That was until discoveries at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) laid the groundwork for major medical advances.

CSHL breakthroughs led to research that helped the U.S. ramp up penicillin production and allowed for the drug to be more easily administered. This turned penicillin into “a weapon that saves lives,” as touted by a 1944 advertisement.

Before this, penicillin worked but wasn’t easy to make. It took a liter of the Penicillium mold to produce just a few milligrams of the drug. That wasn’t nearly enough to treat all injured Allied soldiers or to prevent infected wounds from killing them, as occurred during WWI.

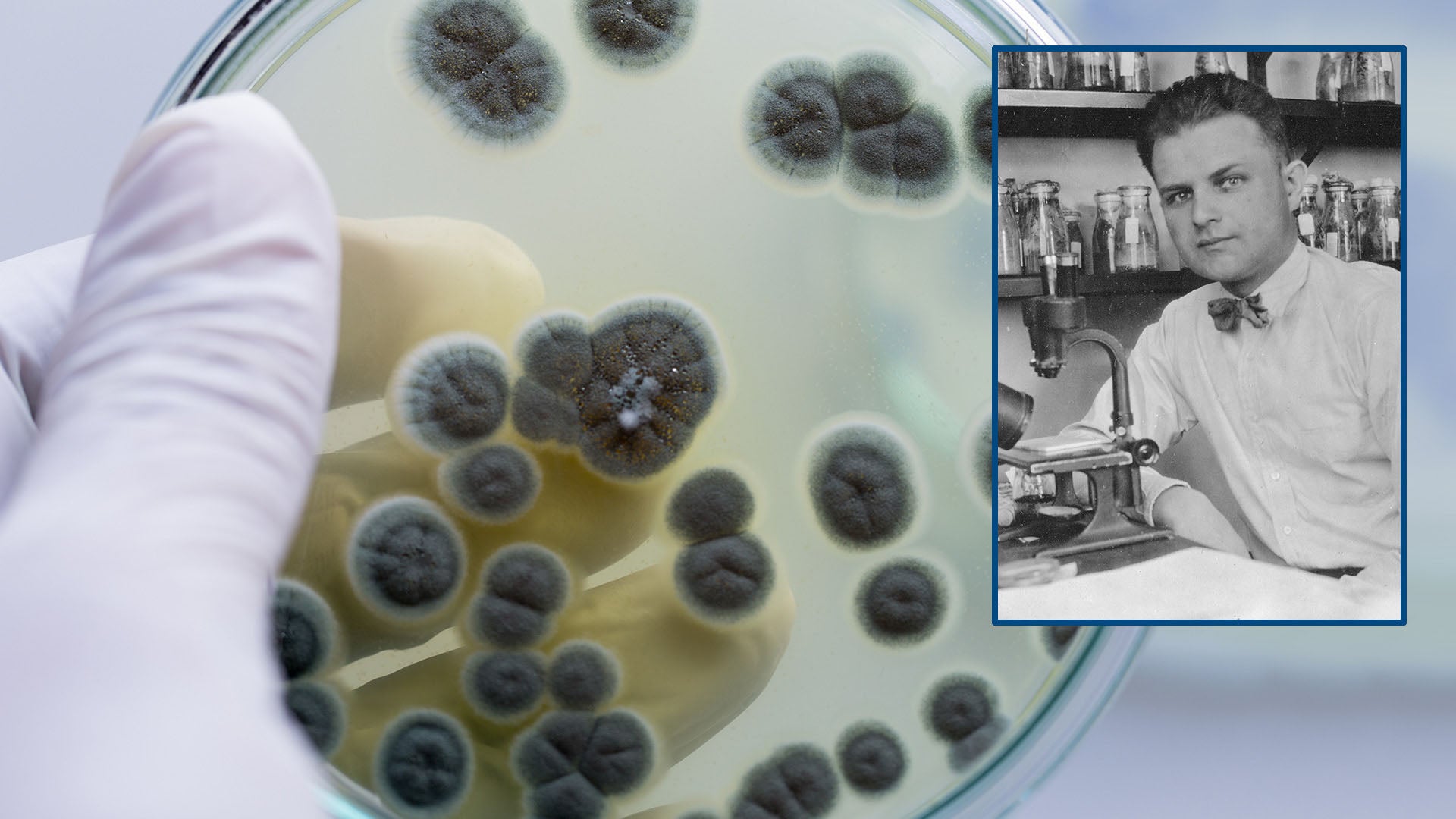

Milislav Demerec, director of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (a forerunner to modern-day CSHL), helped change all that. An expert on using X-rays to induce mutations in fruit flies, he applied this technique to Penicillium to see if he could spur the mold to produce more penicillin.

Demerec and his team tested 5,000 strains and identified 504 with promise. From those samples, researchers were able to find a strain that generated double the yield. That strain was then further mutated at the University of Wisconsin, building upon Demerec’s initial work. Now, penicillin could be made faster at a much lower cost. Production ramped up. For D-Day alone, scientists made more than 2 million doses.

Demerec’s discovery didn’t just aid the U.S. in its war efforts. It also helped cement our country’s role as a world leader in biomedical research.

While Demerec was X-raying Penicillium, Harold Alexander Abramson was looking for a better way to deliver penicillin. In 1941, at Mount Sinai Hospital, he became the first person to administer an aerosolized version of the drug. This fine mist could give medics the power to deliver antibiotics directly to infected tissue.

One year later, Abramson headed up a project at the Long Island Biological Association (another CSHL forerunner) with funding from the War Department. This led to the development of the Cold Spring Harbor Aerosolizer. The nozzle would be used for smoke screens, decontamination, and, most importantly, better delivery of penicillin.

Aerosolized antibiotics are still in use today. They treat infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, bronchitis, and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Penicillin continues to be deployed against infections as well.

When it comes to CSHL’s role in all this, a local news article from 1948 might have put things best. Describing Demerec’s patent for the new, high-yield penicillin strain, the author wrote, “it can be said that the present wide availability of this drug, at much lower cost than formerly, is directly owing to the application of genetical research.” Those words ring true today.

Written by: Jen A. Miller | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455