Her visit was the idea of Mrs. Meyer’s son, Richard, who wanted to bring her back to the Lab as a birthday present. He remembered all the times she had enthusiastically described working here, and despite living in the Glen Cove area Mrs. Meyer had not been back to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory since she left.

She described to us her natural curiosity and her love for science, which she was encouraged to pursue by her family. This runs contrary to the conventional view we have of the history of prejudice against women in science. Was she an exception? Mrs. Meyer did not seem to think so, and in fact interacted with many women scientists both at the Lab and at Pfizer.

After college Mrs. Meyer went to work for Pfizer at its plant in Brooklyn, which is now defunct but has received a second life as a food startup incubator. Her time there coincided with the Second World War and the extremely busy industry of increasing the yield of penicillin and streptomycin antibiotics for the troops overseas, who were succumbing to bacterial infections in the field.

Following her time at Pfizer Mrs. Meyer spent a brief and unsatisfactory stint at an industrial company contributing to the science of paint and other chemical manufacturing. Determined to continue in science, however, she made an inquiry to Dr. Milislav Demerec about working at Cold Spring Harbor, then run by the Carnegie Institute of Washington (CIW), and was asked to make the trip out to meet with him.

It was, doubtless, her experience working with bacteria and antibiotics at Pfizer, and a good word on her behalf by her supervisor there, that led to her eventual hiring by Demerec, who by then had started working on the genetics of antibiotic resistance in bacteria in addition to his research on Drosophila genetics.

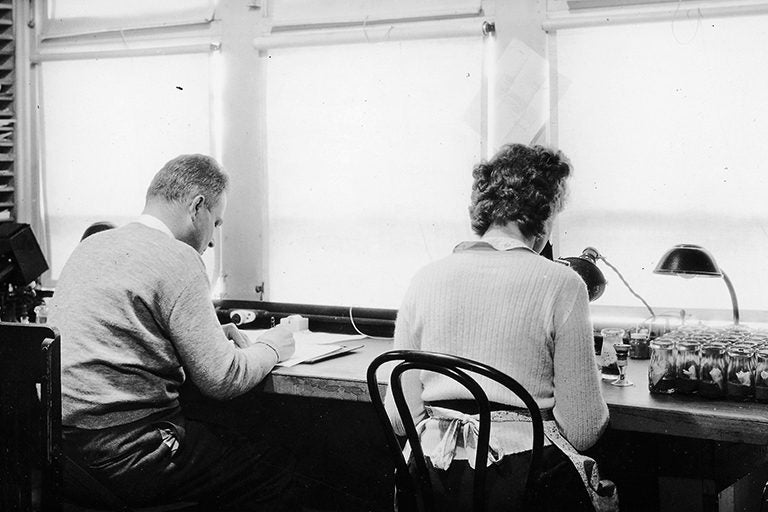

The follow-up letter from Mrs. Meyer after her visit, and letter of employment from Dr. Demerec, survive in the CSHL archives and photographs accompanying this post show her going through the archive materials with Clare Clark, an archivist at the Carnegie Library.

As we walked around the top floor of the Carnegie Library, Mrs. Meyer looked around, trying to place where her bench, and the offices of Dr. Demerec and the other scientists, would have been within the current layout. While the building has changed much since then, we were able to roughly pinpoint where she would have worked.

The new extension at the back of the library blocks the view she remembers, out over the watery marsh of the harbor. However, she spoke of taking time to look up from her microscope and look out of the window in between experiments on the growth of bacteria and changes induced by antibiotics. Her name was mentioned in connection to these studies in the annual report for the year 1950, the citation for which can bee seen at the bottom of this post.

Mrs. Meyer talked fondly of Dr. Demerec, saying he could not have done more for his staff. She recalled that he “would know each person by name and enquire after their family,” and that “he would wander round the lab at night turning off the lights of the empty rooms,” noting also “we had to save money in those days and Dr. Demerec was very conscious of that.”

Mrs. Meyer left CIW late in 1950 and did not go back into science for family reasons. She declined a tour of the rest of the Laboratory in its modern form in order to preserve her memories, saying “I had such a good time here I want to remember it as it was then.” Memory and its preservation being one of the topics of neuroscience research at today’s CSHL, it occurred to us that this was something we could all relate to.

With many thanks to Clare Clark in the library archives for her research and Jessica Giordano in Public Affairs for organizing the tour.

DEMEREC, M., E. M. WITKIN, B. W. CATLIN, J. FLINT, W. L. BELSER, C. DISSOSWAY, F. L KENNEDY, N. W. MEYER and A. SCHWARTZ, 1950 The gene. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Yr. Bk. 49: 144-157.

Cited in Studies of the Streptomycin-Resistance System of Mutations in E. Coli.

Demerec M., Genetics. 1951 Nov;36(6):585-97.