Decades into his career, this pioneer in immunological research realized that turning the immune system on against cancer cells should be easier than turning it off against healthy cells, which was his goal back when he was a doctor seeing autoimmune disease patients. It was a stroke of insight that allowed him and his team to recognize that a drug developed for HIV could treat a completely different kind of disease: pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest cancers of all.

It’s not the kind of achievement you might expect from an undergraduate English Literature major. But Fearon’s chief reason for going to Johns Hopkins Medical School to become a doctor was his lifelong interest in “trying to understand people,” he says. When he learned that the immune system attacks healthy components of the body in autoimmune disease, “that kind of resonated with me because it describes the human condition—we continually do things that are not in our best self-interest.” His very human, English-Literature-major perspective shines through even when he speaks about science and medicine.

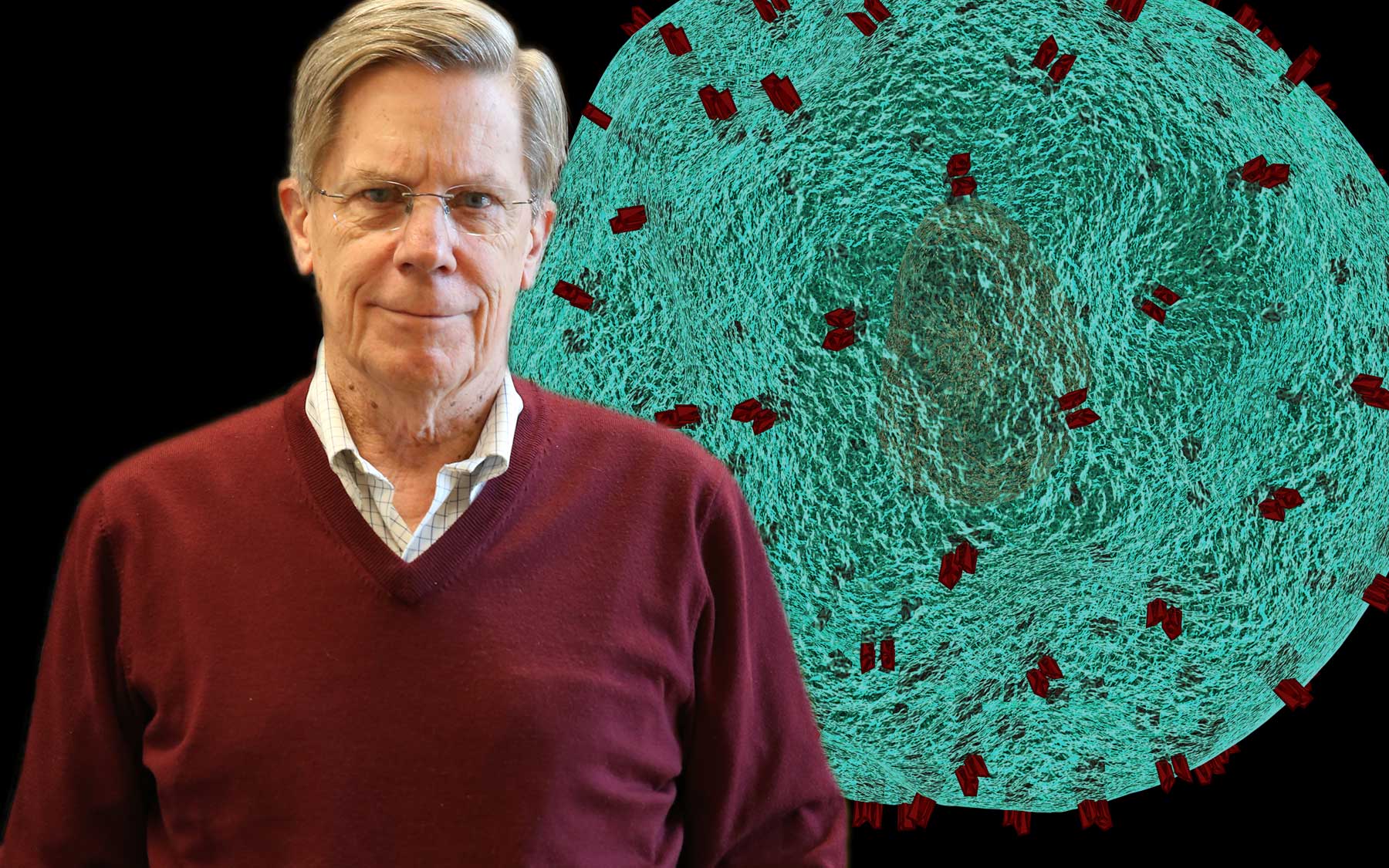

Doug Fearon talked about his “curious” career path and his current research at a recent CSHL public lecture.

While fixing the human condition was clearly too lofty a goal, preventing his patients’ own immune systems from attacking them seemed more reasonable. It didn’t take long for Fearon to realize even that goal would remain out of reach unless he started doing some serious science. Knowledge of the immune system was “so infantile” in the early 1970s during his post-doctoral fellowship at Harvard Medical School, he explains. He felt he could help his patients more by doing research than by administering existing treatments, which were not based on disease mechanisms. Yet, he continued his interest in autoimmune diseases and he became head of rheumatology and of the immunology graduate program at Johns Hopkins Medical School in 1987.

As Fearon delved deeper into the basic science, the deal he made with himself was, “I will stop seeing patients so I can make a discovery that can affect the health of patients.” He became obsessed with learning the biological rules behind immune responses so that he could accomplish this. Therein lies the secret to the success Fearon’s team has had with the pancreatic cancer immunotherapy drug now in clinical trials, called AMD3100.

If the immune system is your body’s army, the problem in fighting cancer is that the general has failed to identify the cancer cells as a threat. So, the army moves on. Fearon’s goal has been to learn the army’s structure so that he can send a message to the general and get the whole army to fight the cancer. That is essentially what AMD3100 does, on a molecular level. It blocks a molecular signal that tells the immune system “you’re not needed here” so that the whole immune army will attack the cancer.

The drug was originally developed for HIV because the virus exploits that same molecular signal to protect itself from the immune system. But once the immune system learns of a threat, it remembers the threat forever. That’s what makes it so difficult to stop the immune system from attacking healthy cells in autoimmune diseases, and easier to recruit the immune system against cancer.

Video of a killer T-cell hunting down cancer cells, created by scientists in Gillian Griffiths’ Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, who collaborate closely with Fearon’s team at CSHL.

Fearon’s approach is completely different from that of one important innovative immunotherapy approach currently approved for use in the United States, known as a CAR T-cell therapy. That strategy involves harvesting T-cells, a type of immune cell, from cancer patients and then genetically engineering them to become super soldiers that target the individual’s cancer. But Fearon has long believed that “you don’t need Rambo”—these individually targeted killer immune cells—because “the ordinary foot soldier will do the job if you let him.” He knows all too well from his work in autoimmune disease that the “foot soldiers” of the natural immune system are already incredibly powerful.

AMD3100 is now making its way through a clinical trial at Cambridge University, where Fearon is still a member of the faculty in addition to his post at CSHL. His team here is working to show exactly how the drug helps the immune system fight pancreatic cancer. He believes that the greatest impact will come by working within the rules of the immune system that he helped establish throughout his career. “I don’t like trying to escape having to do the hard work of understanding the rules,” Fearon maintains. That’s exactly what makes him a perfect fit here at CSHL, where the road to medical progress has always been through the hard work of basic science.