Prostate cancer is the most common non-skin cancer among American men, but most of the prostate cancer researchers at CSHL have zero risk of developing the disease.

The majority of the prostate cancer researchers at CSHL are part of the population that will never get this disease: women. Growing a mo’ for “Movember”—a men’s health awareness and fundraising campaign held each November, symbolized by the MOustache—isn’t an option for them. Instead, they proudly don fake moustaches for the occasion.

“Even if it’s a kind of tumor that will never affect women, it’s one of the main tumors in men,” says Irene Casanova Salas, a postdoc in the research lab headed by Associate Professor Lloyd Trotman, which is focusing on prostate cancer. Before joining Trotman’s team, she worked at an oncology hospital where she saw the extent of the problem firsthand. Among American men, prostate cancer is the 2nd leading cause of cancer death and the most common cancer other than skin cancer, according to the American Cancer Society (pdf).

If there’s a silver lining for researchers in the prevalence of prostate cancer, it’s that there are plenty of patients whose tumors can be studied—although getting access to samples can be tough. It’s a difficulty that Salas and her colleagues, including postdoc Grinu Mathew, were able to overcome thanks to CSHL’s affiliation with the Northwell Health network. Salas and Mathew will use over 100 patient samples to explore the genetic changes within prostate cancer cells that occur when they become more invasive and spread to other tissues such as bone. Appropriately, that project is beginning this November.

This won’t require putting patients through additional procedures, because “the unique thing about this project is that we’re being as noninvasive as possible by using only materials from necessary procedures,” Mathew explains. When a prostate cancer patient goes in for a biopsy, a standard procedure for extracting cells from the tumor, some tumor cells get left behind on the needle. Mathew will use those cells—“the leftovers,” Salas calls them—for her research. Patients also routinely get blood drawn, some of which will now be made available to Salas for her work.

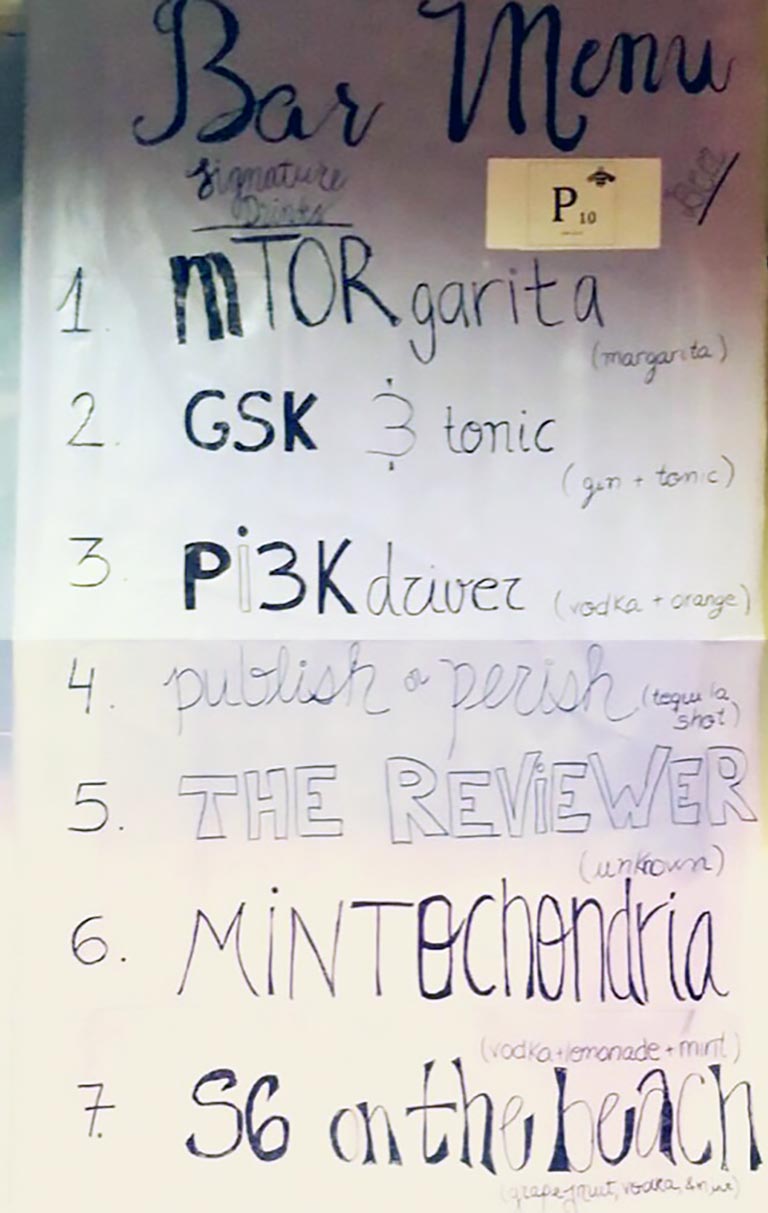

Though prostate cancer will never strike their own bodies, the disease has certainly made its mark on their minds. Even on a Friday night away from the lab bench, Salas, Mathew, and other lab members might be found sipping mTORgaritas and PI3k drivers—their prostate cancer research-inspired twists on the margarita and screwdriver. It’s the kind of get-together that’s true to the spirit of Movember: having fun even while remaining focused on finding solutions to serious problems like prostate cancer.

In case you’re wondering, that jumble of letters and numbers, PI3K, represents a pathway in cells that activates cancer genes when struck with “driver mutations.” Hence, too, the play on “screwdriver.” The “mTORgarita” refers to a cellular pathway called mTOR that becomes more active in prostate cancer cells than it is in normal cells, helping to drive the cancer process forward.

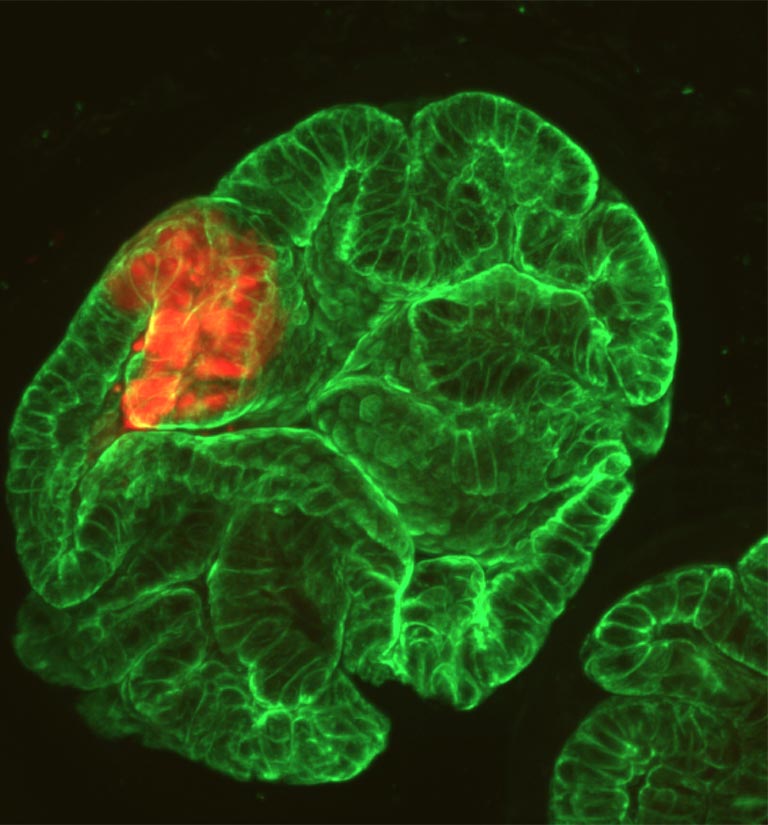

Salas and Mathew will look at the genomes of cancer cells in each patient sample to see whether there are abnormalities in genes that control these key pathways and others. They will then compare what they’re seeing in the genomes of the cancer cells to what those same patients’ doctors are seeing in the clinic.

The hope is that what they learn will help doctors determine how likely it is that a patient’s cancer will spread from the prostate to other parts of the body. This is crucial in prostate cancer, because this type of cancer usually is not dangerous as long as it’s confined to the prostate. As a result, patients need not undergo risky treatments with serious side effects unless doctor’s know the tumor is likely to spread. Right now, the only way to gauge the need for treatment is by looking at the cells in the tumor, and this method cannot distinguish between aggressive and non-aggressive prostate cancer.

Read about how Trotman Lab member Dawid Nowak is contributing to the fight against prostate cancer

Other members of the Trotman Lab are also contributing to this effort. Salas and Mathew emphasize the importance of using the mouse models of the disease that other lab members have developed to further explore the trends they see in cells from patients. It’s a reminder that defeating prostate cancer must be a team effort—and it’s not just a man’s battle.