‘DNA Sudoku’ pools multitude of DNA samples for sequencing in manner analogous to solving a Sudoku grid

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — A math-based game that has taken the world by storm with its ability to delight and puzzle may now be poised to revolutionize the fast-changing world of genome sequencing and the field of medical genetics, suggests a new report by a team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). The report will be published as the cover story in the July 1st issue of the journal Genome Research.

Combining a 2,000-year-old Chinese math theorem with concepts from cryptology, the CSHL scientists have devised “DNA Sudoku.” The strategy allows tens of thousands of DNA samples to be combined, and their sequences—the order in which the letters of the DNA alphabet (A, T, G, and C) line up in the genome—to be determined all at once.

This achievement is in stark contrast to past approaches that allowed only a single DNA sample to be sequenced at a time. It also significantly improves upon current approaches that, at best, can combine hundreds of samples for sequencing.

“In theory, it is possible to use the Sudoku method to sequence more than a hundred thousand DNA samples,” says CSHL Professor Gregory Hannon, Ph.D., a genomics expert and leader of the team that invented the “Sudoku” approach. At that level of efficiency, it promises to reduce costs dramatically. A sequencing project that costs upwards of $10 million using conventional methods may be accomplished for $50,000 to $80,000 using DNA Sudoku, he estimates.

Originally devised to overcome a sequencing limitation that dogged one of the Hannon lab’s research projects, the new method has tremendous potential for clinical applications. It can be used, says Hannon, to analyze specific regions of the genomes of a large population and identify individuals who carry mutations that cause genetic diseases—a process known as genotyping.

The CSHL team has already begun to explore this possibility via a collaboration with Dor Yeshorim, a New York-based organization that has collected DNA from thousands of members of Orthodox Jewish communities. The organization’s aim is to prevent genetic diseases such as Tay-Sachs or cystic fibrosis that occur frequently within specific ethnic populations. The team’s new method will now allow the many thousands of DNA samples gathered by Dor Yeshorim to be processed and sequenced in a single time-saving and cost-effective experiment, which should identify individuals who carry disease-causing mutations.

The advantages of DNA Sudoku

The mixing together and simultaneous sequencing of a massive number of DNA samples is known as multiplexing. In previous multiplexing approaches, scientists first tagged each sample with a barcode—a short string of DNA letters known as oligonucleotides—before mixing it with other samples that also had unique tags. After the sample mix had been sequenced, scientists could use the barcode tags on the resulting sequences as identification markers and thus tell which sequence belonged to which sample.

“But this approach is very limiting,” explains Yaniv Erlich, a graduate student in the Hannon laboratory and first author on the “DNA Sudoku” paper. “It’s time-consuming and costly to have to design a unique barcode for each sample prior to sequencing, especially if the number of samples runs in the thousands.”

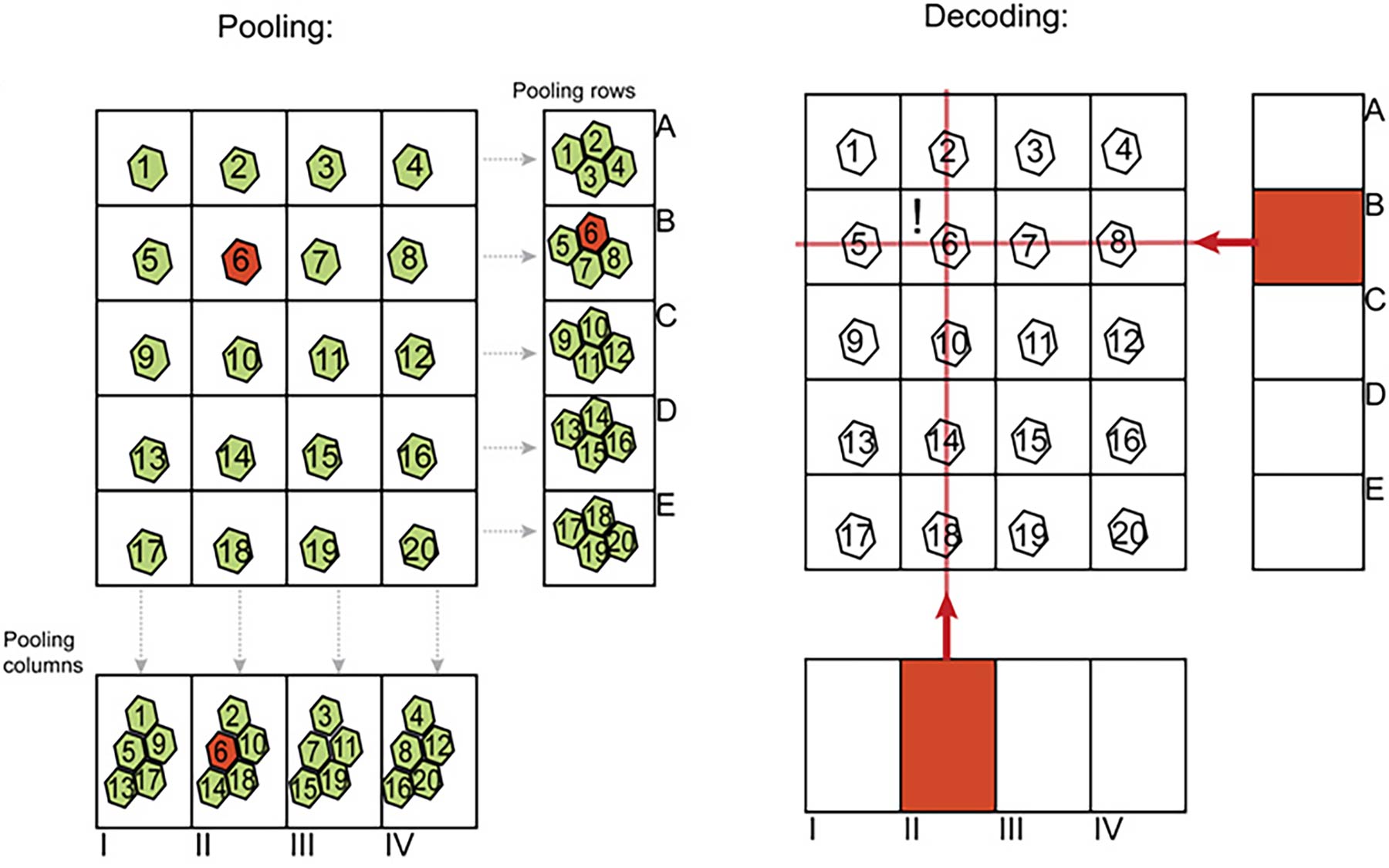

In order to circumvent this limitation, Erlich and others in the Hannon lab came up with the idea of mixing the samples in specific patterns, thereby creating pools of samples. And instead of tagging the individual samples within each pool, the scientists tagged each pool as a whole with one barcode. “Since we know which pool contains which samples, we can link a sequence to an individual sample with high confidence,” says Erlich.

The key to the team’s innovation is the pooling strategy, which is based on the 2,000-year-old Chinese remainder theorem. “It minimizes the number of pools and the amount of sequencing,” says Hannon of their method, which they dubbed “DNA Sudoku” because of its similarity to the logic and combinatorial number-placement rules used in the popular game.

The method, which the CSHL team has patented, is currently best suited for genotype analyses that require only short segments of an individual’s genome to be sequenced to find out if the individual is carrying a certain variant of a gene or a rare mutation. But as sequencing technologies improve and researchers gain the ability to generate sequences for longer segments of the genome, Hannon envisions wider clinical applications for their method such as HLA typing, already an important diagnostic tool for autoimmune diseases, cancer, and for predicting the risk of organ transplantation.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Citation

“DNA Sudoku—harnessing high-throughput sequencing for multiplexed specimen analysis” appears in the July 1st print issue of Genome Research. The full citation is: Yaniv Erlich, Kenneth Chang, Assaf Gordon, Roy Ronen, Oron Navon, Michelle Rooks, and Gregory J. Hannon. This article is available online at http://genome.cshlp.org/content/early/2009/05/15/gr.092957.109.full.pdf+html (doi:10.1101/gr.092957.109)