A method that could be applied widely to explore genetic basis of cancer drug resistance

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Why do cancer patients develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs, sometimes abruptly, after a period in which the drugs seem to be working well to reduce tumors or hold them in check? Although largely a mystery to scientists, the result when this occurs is all too familiar: patients relapse and in many cases die when their cancers become resistant.

A team of researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), seeking to understand the genetic underpinnings of cancer therapy response, have identified what they regard a “significant contributor to resistance.” Using a novel screening technique involving “pools” of gene-regulating short RNA molecules, they were able to determine how resistance to a drug called doxorubicin arises in lymphomas occurring in a particular strain of mice.

Toward a “global view” of factors influencing therapy response

“The method we developed is notable,” said CSHL Professor Scott W. Lowe, Ph.D., a leader of the research team, “because it gives us a view of how resistance works at the level of individual molecules in living animals, and also because it can be easily extended to other chemotherapy drugs and tumor systems to give a potentially global view of factors that mediate response to cancer therapy.”

Many genetic factors are already known to influence the effectiveness of anti-cancer drugs. Such factors manifest themselves in a variety of ways, some of them remarkable. One known gene change, for instance, results in increased expression of pump-like mechanisms that remove chemotherapeutic toxins from cancer cells; another causes changes in cellular structure that prevent drug molecules from “docking” with their targets.

The research by the CSHL team, which included Professors W. Richard McCombie, Ph.D., and Gregory J. Hannon, Ph.D., in addition to Dr. Lowe, demonstrated the mechanism of one form of resistance in cell culture and living mice. These results were reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on July 1.

Confirming Doxorubicin’s Mechanism of Action

In exploring mechanisms of resistance to doxorubicin (sold under the name Adriamycin), the CSHL team first sought to confirm its mechanism of action. They knew in advance that the drug is part of a family thought to interfere with a class of enzymes called topoisomerases. These enzymes normally act to loosen or relax tightly coiled strands of the genetic material, DNA, and in so doing play an important role in the complex, multi-step process by which cells divide and multiply.

By interfering with topoisomerases in cancer cells, doxorubicin and other drugs in the same class including etoposide and camptothecin derivatives have been thought to prevent cancer cells from proliferating. Their effectiveness as front-line treatments is beyond dispute; the problem with these drugs arises when cancer cells somehow become resistant to them.

“If we want to get better results with anticancer drugs like doxorubicin,” said Dr. Lowe, “we have to determine definitively their mechanism of action. Once known, the way is open to try to circumvent or short-circuit this process.”

Regulating topoisomerase through gene “knockdown”

The premise of the CSHL team’s experiments was to find short RNA molecules that, via a mechanism called RNA interference, or RNAi, could regulate the gene or genes responsible for the effectiveness of chemotherapy treatment. The practical question for the team was which short RNAs, precisely, would have this effect?

Dr. Hannon and colleagues in recent years have generated libraries of many thousands of so-called short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), each of which is capable of interfering with the expression of a specific gene or genes.

“In these experiments, we chose to survey a group of shRNAs that target a set of genes that scientists call ‘the cancer 1,000’” Dr. Hannon explained. “These are a set of known or putative cancer-relevant genes that previous research has identified.” In all, there are about 2,300 shRNAs in this cancer-specific set that target genes in the mouse genome.

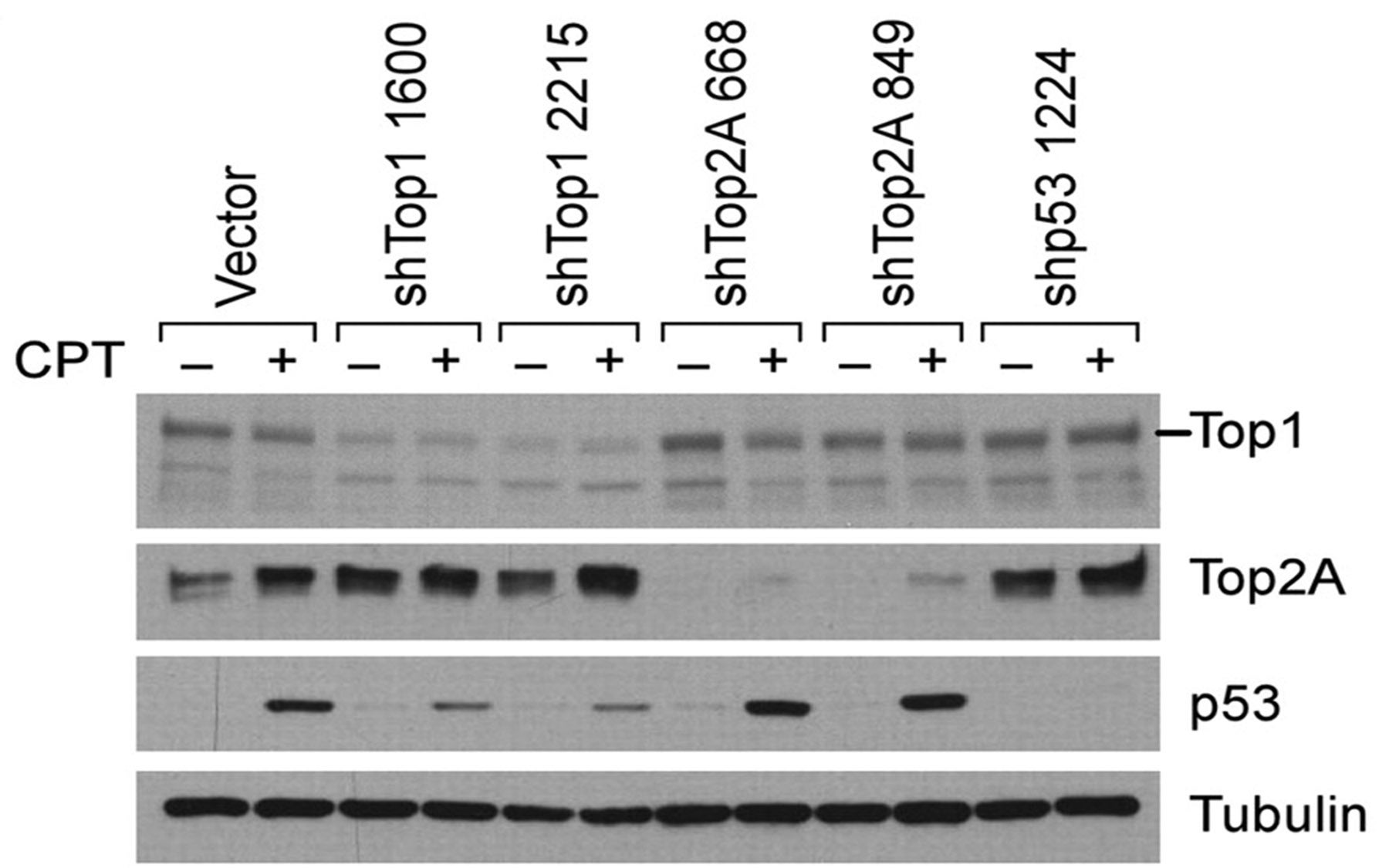

By screening subsets or “pools” of them, the team was able to identify shRNAs that specifically interfered with the expression of genes involved in producing topoisomerase enzymes. Four shRNAs were identified that specifically and consistently interfered with a gene called Top2A, which codes for production of a particular topoisomerase called topoisomerase 2α.

Gene knockdown, drug resistance, and an unexpected synergy

After “knocking down” the Top2A gene in mouse lymphoma cells grown in culture, the team observed resistance to doxorubicin. “Previous work had suggested a relationship between Top2A levels and sensitivity to doxorubicin,” noted Dr. Lowe, “yet the effect had not been validated in living animals.” When the team used shRNAs to target the Top2A gene in living mice with lymphoma, the same result was obtained: when the gene was “down-regulated,” the mice developed resistance to the drug.

In the same series of experiments an unexpected finding emerged. Short-hairpin RNAs specifically targeting the gene for another of the topoisomerase enzymes—a gene called Top1—had the effect of significantly increasing the effectiveness of the topoisomerase 2α poisons including doxorubicin and etoposide. “By knocking down the Top1 gene, we witnessed a kind of synergistic effect: an increase in the effectiveness of drugs targeting the enzymes coded for by Top2,” Dr. Lowe said.

This raised the broader question of how the status of various topoisomerases in cancer cells following treatment relates to treatment effectiveness. The team correlated Top1 and Top2A expression levels with tumor relapse rate in living mice. In half of the relapsed tumors observed following doxorubicin treatment, Top2A levels were dramatically reduced—without manipulating gene expression with shRNAs.

Along with the finding that Top1 knockdown hypersensitized cells for doxorubicin treatment, this result suggested to the CSHL researchers that “alterations in topoisomerase expression levels represent one of undoubtedly many therapy resistance mechanisms which can play a substantial role in chemotherapy response in vivo.”

According to Dr. Lowe, “The methods we used in this study can easily be extended for use with other chemotherapeutic agents and tumor systems, to allow a more global view of factors that mediate the response to therapy.”

Written by: Communications Department | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Citation

“Topoisomerase levels determine chemotherapy response in vitro and in vivo” appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on July 1, 2008. The full citation is: Darren J. Burgess, Jason Doles, Lars Zender, Wen Xue, Beicong Ma, W. Richard McCombie, Gregory J. Hannon, Scott W. Lowe and Michael T. Hermann. The paper can be obtained online: http://www.pnas.org/content/105/26/9053.full.pdf+html