GAT1 encodes an enzyme that maintains flow of information through transport channels

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Plant cells communicate via microscopic channels called plasmodesmata that are embedded in their cell walls. For the stem cells in the plants’ growing tips, called “meristems,” the plasmodesmata are lifelines, allowing nutrients and genetic instructions for growth to flow in.

Developmental and environmental cues trigger changes in the structure of the tiny channels, thereby altering the flow of traffic through them. The genes and molecular pathways of the plant cell that respond to these cues, and the mechanisms that control channel structure and cell-to-cell traffic are, however, mostly unknown.

To identify these genes, a team of researchers led by Professor David Jackson, Ph.D., at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), devised a method to find mutant cells whose channels were blocked to traffic. The experiments have revealed a gene called GAT1 (pronounced gate-one), which instructs cells to produce an enzyme found only in meristems, the stem-cell rich tip of the plant where new growth takes place. The enzyme improves the flow of traffic through plasmodesmata by acting as an antioxidant, a type of molecule that relieves cellular stress.

“This discovery is one of the first examples of using genetics to understand how plant cells communicate through plasmodesmata,” says Jackson, whose lab at CSHL is devoted to the study of plant genetics. “Our study suggests a mechanism through which plant cells can adjust trafficking in these channels through the various stages of development.” The team’s findings will be published in the Feb 17th issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

GAT1 keeps callose at bay

As plants develop, growth signals and environmental cues such as damage or stress trigger overproduction of a substance called callose. Although callose is a normal structural component of cell walls in plants, excess callose accumulates and forms obstructive clumps that plug the plasmodesmata and impede the flow of traffic through the channels.

Restricting flow can be beneficial in some instances, such as when damaged parts need to be closed off or virus-infected cells need to be quarantined. But flow blockage can be fatal too, especially when it happens in meristems.

“Meristems that are blocked and thereby starved of nutrients won’t give rise to daughter cells and spawn new organs, thus stunting the plant’s growth,” explains Jackson. “What we’ve found now is probably the mechanism that normally prevents blockages from occurring in these stem cells.”

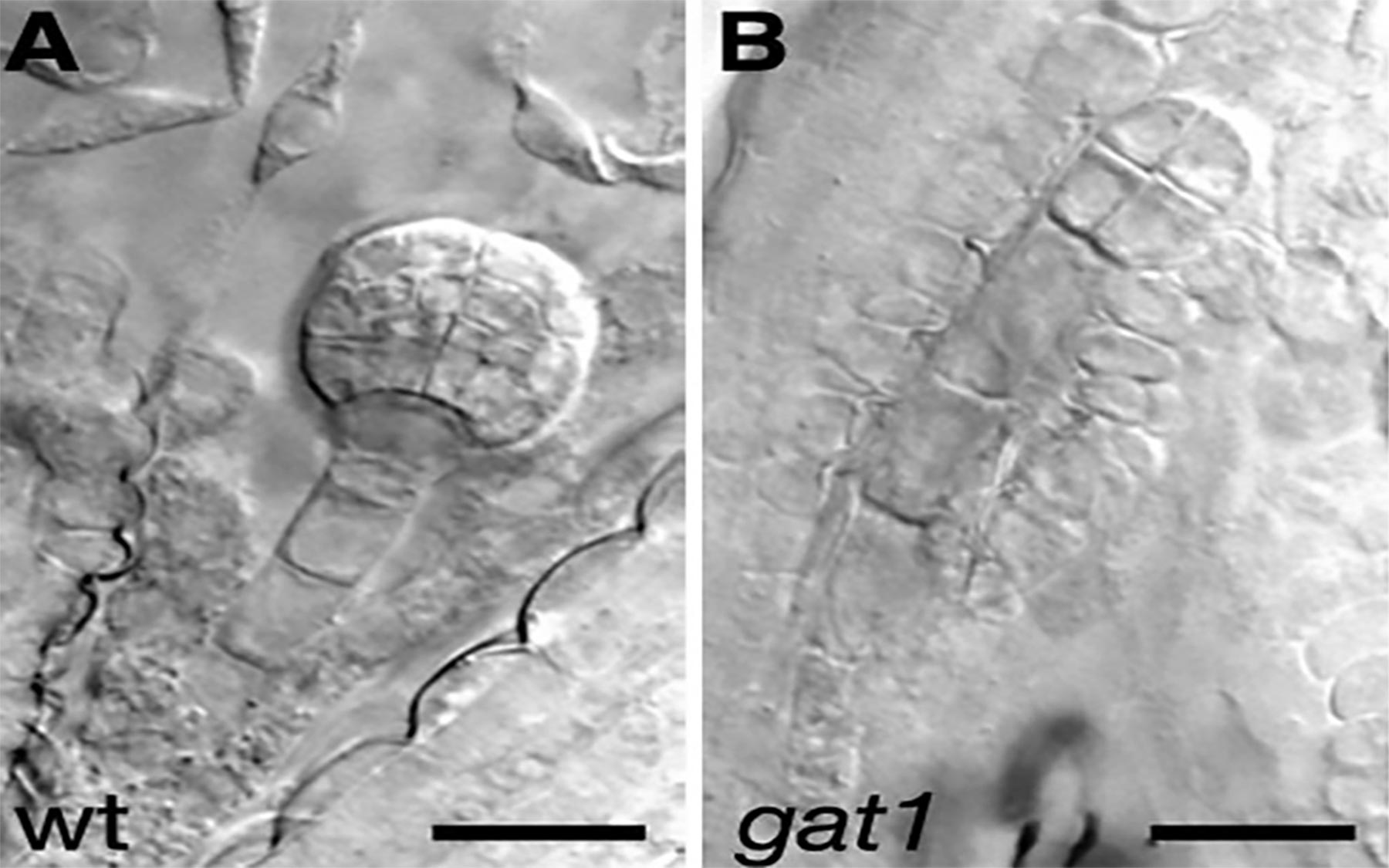

Jackson’s team has found that plants stave off callose accumulation and keep the channels open by turning on the GAT1 gene in their stem cells. Seeds in which this gene failed to work were observed by the CSHL team to give rise to seedlings that barely survived more than two weeks, despite forming intact roots and an intact phloem—the main transport artery that carries nutrients and other supplies to the meristems.

The mutants even had intact meristems that had developed the required numbers of transport channels. These channels, however, were functionally defective, as the pile-up of callose narrowed them, making the passage of nutrient molecules impossible. The CSHL scientists were able to reverse this defect by re-introducing a functional GAT1 gene into mutant plants. When the GAT1 gene was turned on, the production and accumulation of callose decreased.

GAT1 counters oxidative stress

One of the distress signals that spur cells to synthesize callose are oxygen free radicals—the same cell-damaging molecules that have gained notoriety as a major cause of cell death and aging. In mutant plant seeds that lack a functional GAT1 gene, stem cells brim with high levels of these free radicals and other toxic ions, collectively known as reactive oxygen species (ROS).

This ROS threat, according to Jackson’s team, is normally counterbalanced by GAT1. The CSHL scientists found that this gene encodes an enzyme called thioredoxin-m3, which they found only in the meristems, as well as in the tissues dedicated to transport. There, it acts as an antioxidant—a molecule that slows or prevents the formation of ROS.

Thioredoxin-m3 is a member of a large family of small proteins that are ubiquitous in plant and animal cells, and are biochemical workhorses that meddle in multiple metabolic processes. They consequently have an impact on numerous cellular events, including stress responses, cell death, and gene expression.

In addition to protecting plants against oxidative damage, as the CSHL scientists have shown, thioredoxin-m3 and its cousins might have other specific functions in different stages of plant development in different tissues and under different physiological conditions. Knowing the diverse functions of these proteins may help in engineering plants that are drought- and heat-tolerant.

Discovering the role of thioredozin-m3 in cell-cell traffic within meristems has already provided one such payoff. Jackson’s group found that increasing the expression of GAT1 in plants caused them to take longer to produce flowers and enter senescence—the period of old age. “People are generally interested in controlling senescence for commercial purposes such as growing plants that last longer or flowers that stay fresh longer,” explains Jackson. “Our results suggest that manipulating GAT1 expression in plants can be one way of achieving this,” he says.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Citation

“Control of Arabidopsis meristem development by thioredoxin-dependent regulation of intercellular transport” appears in the Feb 17th issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The full citation is: Yoselin Benitez-Alfonso, Michelle Cilia, Adrianna San Roman, Carole Thomas, Andy Maule, Stephen Hearn, and David Jackson.

This article is available online at http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2009/02/12/0808717106.full.pdf+html (doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808717106)