The sandy shores of New York’s Cold Spring Harbor have been home to over a century of groundbreaking biological research. But pioneering science doesn’t usually happen in a vacuum. Since 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) and its predecessors have brought together scientists from around the world to learn, trade ideas, and collaborate. On March 8, CSHL’s annual Meetings & Courses programs returned for the 2023 season.

Each year, CSHL organizes 25 to 30 scientific conferences, 20 meetings at its Banbury Center think tank, and 30 advanced courses. These programs bring some 9,000 people to the Laboratory’s Long Island campus throughout the year. When Meetings & Courses went virtual due to COVID-19, that number ballooned to about 15,000. Attendees range from grad students to accomplished senior scientists—including Nobel laureates.

Here, we look back on the history of Meetings & Courses programs to see how their evolution has helped push science and our understanding of the world forward.

Meetings & Courses’ early beginnings

July 7, 1890 marks day one of the first course given at The Brooklyn Institute’s Laboratory of Biological Research at Cold Spring Harbor, a predecessor of CSHL. The “General Course in Biology” taught 24 students various research techniques. They learned to collect specimens from the nearby harbor and prepare microscope slides.

Although this is perhaps the earliest example of meetings and courses at CSHL, the Meetings & Courses program traces its roots to the 1930s and ’40s. In 1933, the Carnegie Institute of Washington (CIW) hosted the first of CSHL’s annual Symposia in Quantitative Biology. The formal start of the Laboratory’s Courses program would come 12 years later, with Nobel laureate Max Delbrück’s 1945 Phage Course.

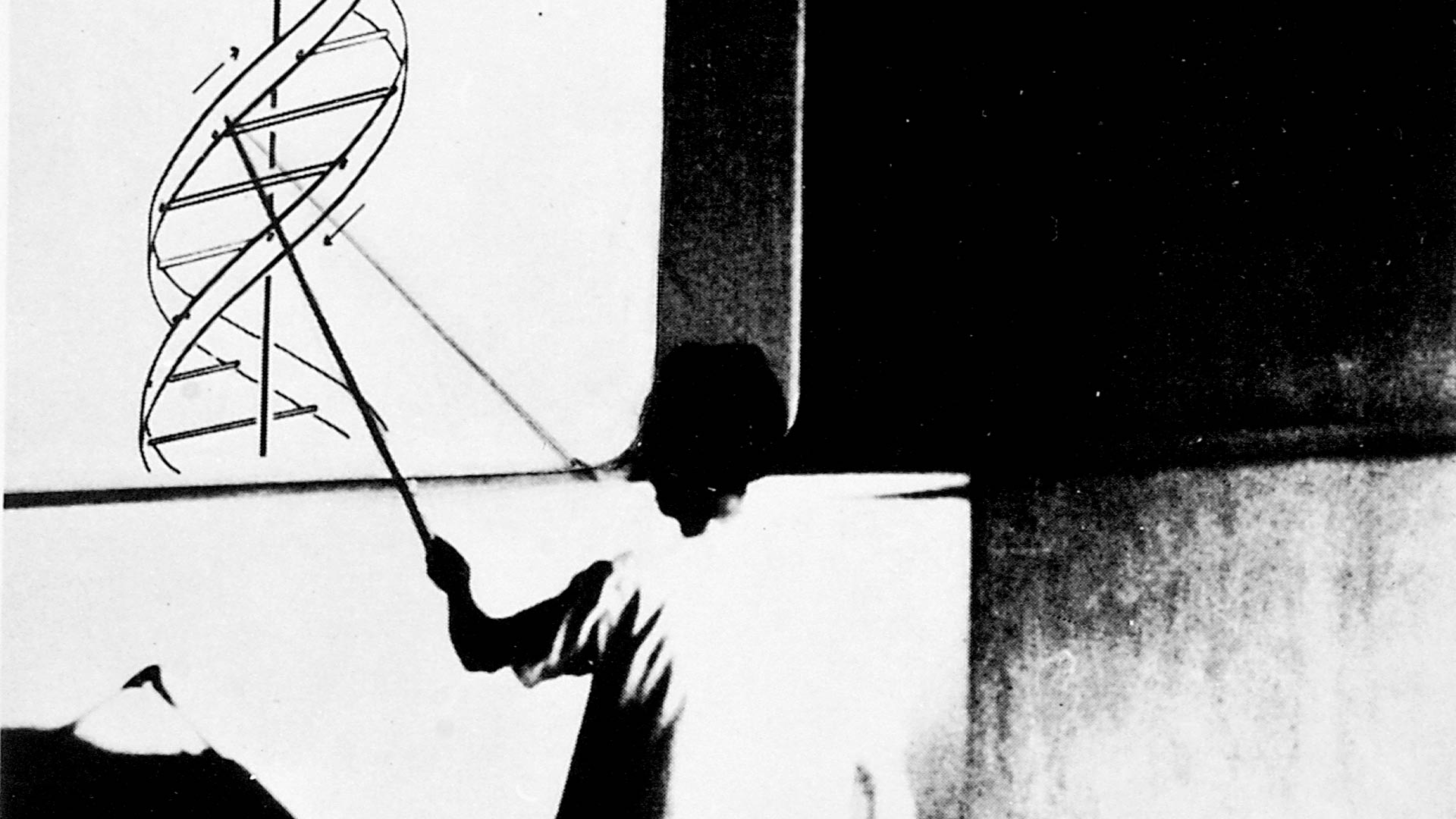

Nobel laureate Alfred Hershey discusses the Hershey-Chase, or “Waring Blender,” experiment conducted with Martha Chase at CSHL in 1952.

Delbrück’s course was one of the first in the field that would become known as molecular biology. It was built on research published in 1943 in collaboration with Salvador Luria. The research would earn both scientists a share of the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with CIW Director Alfred Hershey. Together with Hershey and Martha Chase’s “Waring Blender” experiment, their work confirmed that genetic mutations occur randomly and that DNA is the molecule of heredity.

The importance of these discoveries to our understanding of life on Earth cannot be overstated. Their impact was on display at the 1953 Symposium on Viruses. Twelve of the event’s 50 presenters would go on to win Nobel Prizes in the following 16 years. But the 1953 Symposium would be forever remembered thanks to a late addition.

Just a few months prior, a former student of Delbrück and Luria named James Watson made a discovery that shook the world of genetics to its core. Working with British scientist Francis Crick, Watson identified the twisting-ladder structure of DNA. Following this monumental discovery, Watson was added to the Symposium program at the last minute. There, he gave the first-ever public presentation of the DNA double helix.

This began a “golden age” of research at CSHL and helped establish the CSHL Symposia as the place to be for the latest in molecular genetics. And back then, you really did have to be there.

Remember, before the internet, it was much more challenging to record and distribute scientific findings. Scientists calculated data by punching holes in cards and feeding them to a room-sized computer for analysis. Structural biologists needed thousands of these cards to map a single molecule. If two labs wanted to share this data with each other, they had to send it through the mail. A meeting held over 50 years ago at CSHL changed all of this.

In 1971, CSHL hosted a symposium titled “Structure and Function of Proteins at the Three-Dimensional Level.” There, Nobel laureate Max Perutz started an informal chat on how to collect and distribute protein structure data. This sparked intense discussions all over campus that spilled past official meeting hours.

With support from several leading structural biologists, the public Protein Data Bank (PDB) launched in October 1971. Today, the PDB continues to grow. It now houses over 130,000 protein structures. But its impact proved even greater. Once biologists started to see the benefits, more databanks formed. Science itself became more transparent and accessible. This led to expansion and innovation in many research areas.

Meetings & Courses’ continuing legacies

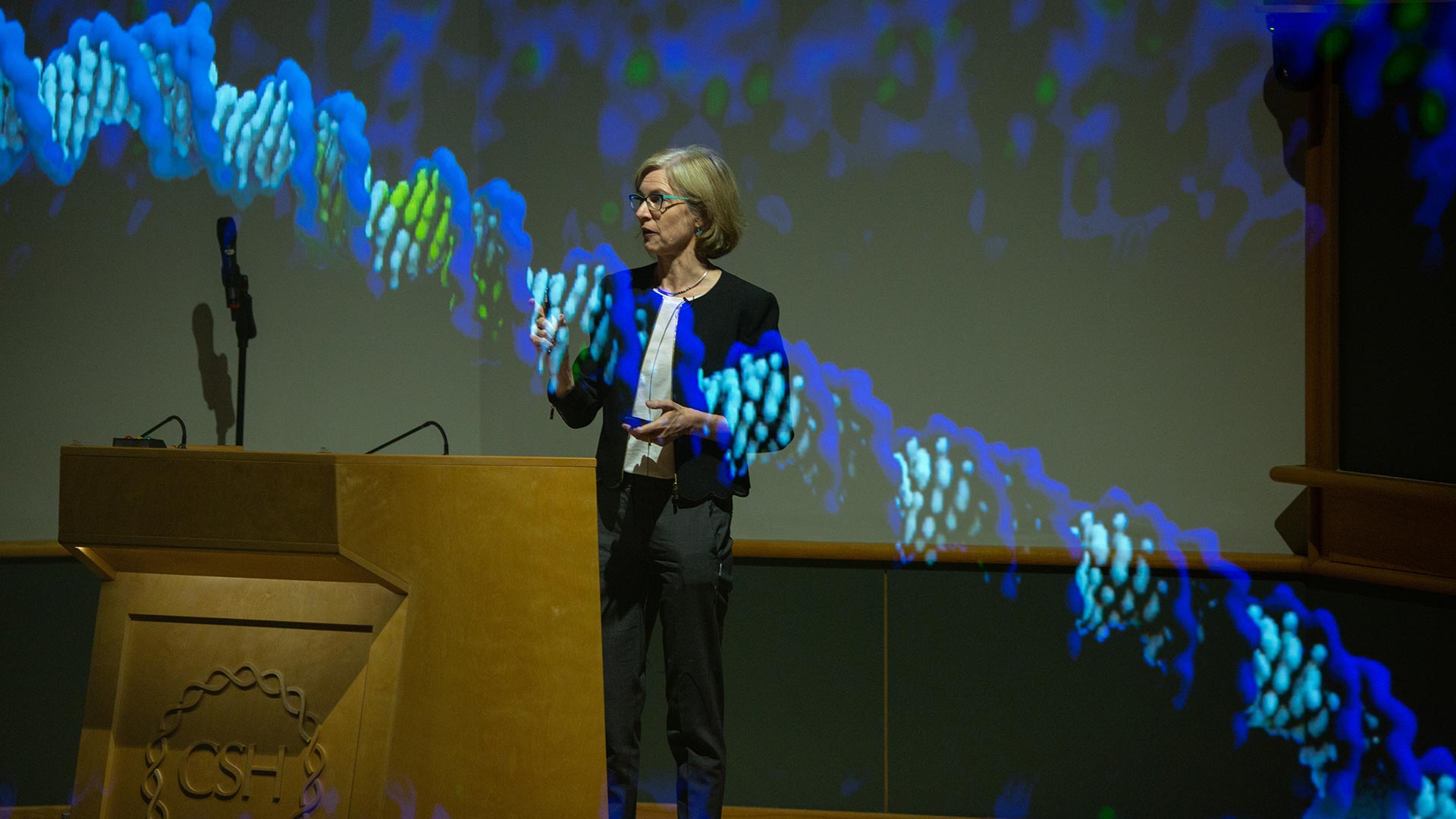

In 2020, Jennifer Doudna received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The genome editing tool has since revolutionized human and agricultural genetics research. It was a milestone in a long and storied career that has intersected with CSHL in many ways, including a 2022 Double Helix Medal.

As a Ph.D. student at Harvard University in the 1980s, Doudna became interested in a molecule called RNA. She often attended meetings and courses at CSHL while researching the molecule’s structure and function.

Five years before her Nobel Prize, Doudna launched an annual CSHL meeting called “Genome Engineering: CRISPR Frontiers.” What started as a small, private discussion on genetic sequencing has become one of the Laboratory’s most popular meetings.

To date, Doudna has spoken at several CSHL Symposia, including the 2019 Dorcas Cummings lecture. Her research has helped move CRISPR from the lab to the clinic. And her presentations at CSHL events have inspired a new generation of geneticists to take her work to new heights.

Of course, Doudna isn’t the only celebrity scientist known to pop up on campus from time to time. CSHL’s meetings are often a who’s who of preeminent researchers. A 2016 conference called “HIV/AIDS Research: Its History and Future” brought together more than 120 of the field’s luminaries. These included Dr. Anthony Fauci as well as 2008 Nobel laureate Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Robert Gallo—two co-discoverers of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Since its emergence, this disease has claimed the lives of more than 40 million people.

CSHL Meetings & Courses’ groundbreaking presentations on HIV/AIDS date back to the epidemic’s earliest days. In September 1983, when the source of these tragic deaths was still a mystery, the Laboratory held a meeting on “Human T-Cell Leukemia Viruses.” There, Luc Montagnier discussed a virus he’d discovered alongside Barré-Sinoussi that would become known as HIV.

To spread awareness and shine a light on HIV/AIDS research, CSHL’s Center for Humanities & History of Modern Biology preserved the entirety of the 2016 conference online. “Oral Histories of Biology, Medicine, and Pandemic Response” launched in 2021. The annotated digital archive provides public access to the four-day symposium and its 49 talks and panels. Included are emotional stories about some of the field’s seminal discoveries.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases from 1984-2022, was a leading voice in the nation’s response to HIV/AIDS and COVID-19. – Video courtesy of CSHL Archives

The hard lessons of the HIV/ADS epidemic would inform the Laboratory’s response to COVID-19. In March 2020, when COVID-19 cases first surged, CSHL took immediate action to help stop the spread of this highly contagious virus. In addition to going virtual, Meetings & Courses pivoted to concentrate on the pandemic. Scientists from more than 80 countries came together via these virtual conferences to share their ideas more widely and openly. Speaking to this unprecedented effort, CSHL’s bioRxiv and medRxiv servers now host more than 26,500 studies on COVID-19.

Meetings & Courses today and tomorrow

As of 2023, CSHL Meetings & Courses counts 10 Nobel laureates amongst its generations of alums. A recent addition to this esteemed class is Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo, winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In 1986, Pääbo attended a CSHL Symposium on the Molecular Biology of Homo Sapiens. Presenter Kary Mullis’ talk on amplifying DNA inspired Pääbo to turn his own research toward the pursuit of ancient genomes. This led to the first-ever sequence of the Neanderthal genome. Pääbo has since attended more than 40 CSHL meetings. He has also organized the annual Biology of Genomes meeting and served on Cold Spring Harbor Asia’s founding Scientific Advisory Board.

Genetic sequencing and analysis are the focus of several meetings and courses in 2023. The year’s first meeting, “Probabilistic Modeling in Genomics,” has already brought together experts from the US, UK, Denmark, and Austria. The first course—on cryo-electron microscopy, a technique used to study individual molecules—begins March 23. Pääbo is slated to attend The Biology of Genomes meeting, which runs from May 9-13. Other topics on this year’s agenda include autism spectrum disorders and the burgeoning field of NeuroAI.

At the end of the CSHL Courses’ spring/summer session, participants compete in the annual Plate Race, running stacks of yeast agar plates around a 200-meter course.

As our understanding of the world continues to evolve, CSHL Meetings & Courses programs remain at the center of international scientific discourse. Executive Director David Stewart attributes the programs’ success to their cutting-edge nature and collaborative environment.

“People can come to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and learn from the experts,” he says. “They can mingle and exchange ideas. You see it happening every year. It’s incredibly intellectually vibrant.”

It’s these connections that drive collaborative research and education. Recognizing that, CSHL is now investing $425 million to expand its reach like never before. The Foundations for the Future campaign will provide new guest housing for Meetings & Courses. This will allow an even greater audience to attend these programs in person. And it will welcome new generations to the global science community.

Written by: Nick Wurm, Communications Specialist | wurm@cshl.edu | 516-367-5940