Video interviews with 22 leaders in the field are freely available online

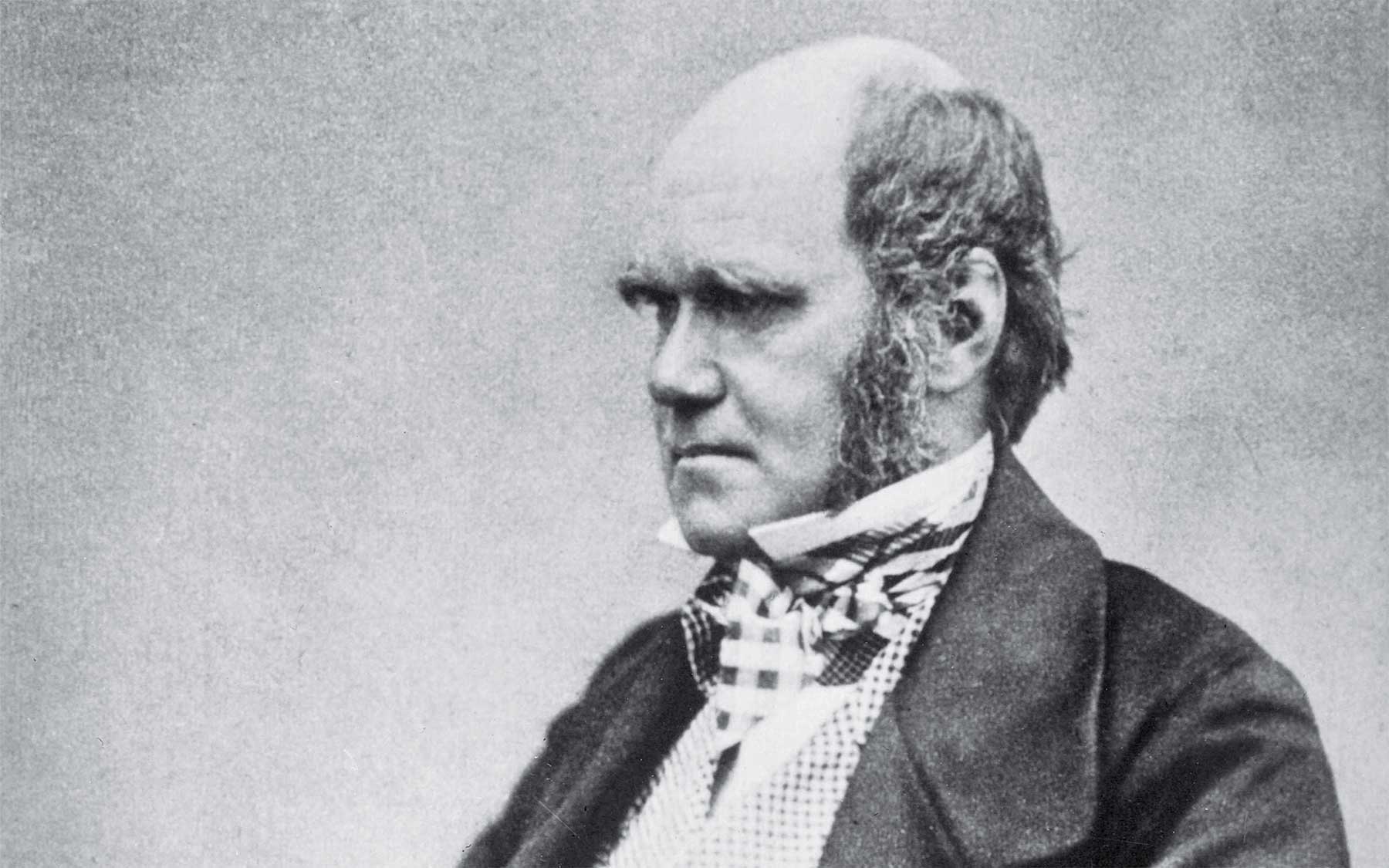

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — To celebrate Charles Darwin’s 200th birthday and the 150th anniversary of his revolutionary work, On the Origin of Species, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) hosted a Symposium entitled “Evolution—the Molecular Landscape” from May 27 to June 1. The meeting, the 74th in CSHL’s historic Symposium series, had a special poignancy in view of the setting. The field of molecular biology, which Darwin could never have contemplated but which has provided profound evidence in support of his epoch-altering ideas, has evolved from a series of seminal courses taught at CSHL in the years immediately following the Second World War.

About 400 scientists gathered at the fast-paced, six day-long conference to discuss a wide range of evolution-themed topics, ranging from the origins of life on a molecular scale to the emergence of species both simple and complex over the last three billion years.

The line-up of speakers comprised a stellar list of preeminent scientists and thinkers such as the zoologist and prolific author E. O. Wilson (Harvard University); genome-sequencing pioneer Craig Venter (J. Craig Venter Institute); and Nobel Prize winner and former president of HHMI Thomas Cech (Colorado Institute for Molecular Biotechnology), to name just a few. Among the invited speakers were CSHL scientists including President Bruce Stillman, leading RNAi researcher Gregory Hannon and epigenetics expert Robert Martienssen.

Sean Carroll: ‘Remarkable creatures’

The meeting kicked off with a well-attended first-night lecture that was open to the public. It featured noted evolutionary biologist and science writer Sean Carroll, an HHMI-funded scientist at the University of Wisconsin. For over an hour, Dr. Carroll charmed the audience with tales of the remarkable adventures undertaken not only by Charles Darwin but by his famous contemporaries, naturalists Alfred Russell Wallace and Henry Bates, both of whom also embarked on globe-trotting expeditions in search of creatures that would help them trace the origin of species. Carroll has chronicled these tales more fully in the newly published Remarkable Creatures: Epic Adventures in the Search for the Origins of Species.

As the meeting unfolded, editors from CSHL Press captured the thoughts and ideas of 22 high-profile attendees in informal and revealing video interviews, which are available as free downloads.

These interviews provided an excellent forum for scientists to expound freely on topics of their interest and expertise, and in a setting more relaxed than their formal, time-limited lectures before plenary sessions of the Symposium. The videos offer an invaluable glimpse into the speakers’ works and their opinions on how their findings have impacted and advanced our understanding of evolution, and in some instances, on controversial topics touching on evolution in today’s headlines.

“We are now slowly understanding that evolution happens in a series of small steps,” Sean Carroll indicates in his Symposium video interview. “The process is like making changes to a car and tinkering with it while it’s engine is still running.” Carroll’s seminal scientific work on genes that control the building and shaping of bodies offers examples, helping to answer some longstanding conundrums in evolutionary theory and revealing the role of gene-controlling DNA sequences (which are likened to “switches”) in formulating evolutionary change on the genomic level.

Craig Venter: Venter’s bid to evolve new life forms

Craig Venter, who was instrumental in helping to map the human genome, spoke of the recent shift in his group’s research focus: from reading the genetic code to writing it. His most recent achievement is to create a synthetic cell—a whole new kind of bacteria, the so-called Mycoplasma laboratorium—by stitching together half a million DNA nucleotides. Venter’s current quest is “to find the minimum set of genes required to create and sustain life, and synthesize chromosomes with these genes,” he says. “We could use organisms with man-made DNA to tackle a host of problems.” He envisions a future in which such synthetic bugs will manufacture biofuels or absorb greenhouse gases, to cite a few examples.

In a welcome addition to talks on evolution in the context of biology, the meeting also included talks on evolution in the context of culture. Matt Ridley, the author or the acclaimed and popular books Genome and Nature via Nurture, entertained the participants with his discussion of what happens When Ideas have Sex: the Role of Exchange in Cultural Evolution.

The historian and author Niall Ferguson noted an important connection between evolution and economics by pointing out that Darwin himself owed a lot to economic thinkers of his time such as Thomas Malthus, whose work, An Essay on the Principle of Population, helped Darwin formulate his own ground-breaking idea of natural selection. “The time may have come for evolutionary biology to return that favor to economics,” says Ferguson in his video interview, even though past attempts to do this have been unsuccessful. “With new fields like evolutionary psychology and behavioral finance emerging, we’re beginning to see a meaningful impact of evolution on economics.”

Eugenie Scott: Intelligent design: ‘If nothing else evolves, Creationism does’

Eugenie Scott, a leading opponent of the teaching of “scientific creationism” in public schools, suggests in her Symposium video interview that public education in the U.S. effectively dodged a bullet in the recent federally adjudicated case of Kitzmiller, et al. v. Dover Area School District. It was the first direct challenge brought in federal court against a school district—in Delaware—that required intelligent design to be taught as an alternative to Darwinian evolution as an account of life’s origins.

Scott is executive director of the National Center for Science Education, Inc., a non-profit representing scientists, educators and others in the promotion of better science education. An advisor to the plaintiffs’ legal team, Scott comments that “one consequence of winning is that we were hearing about lots of school districts that were poised to introduce Dover-like policies—ready to introduce intelligent design into their district [curriculums]. A lot of them pulled back” after the Dover decision, she says, “but, if nothing else evolves, creationism does. The forces of intelligent design have reorganized and leaped into new venues.”

Daniel Dennett, Professor of Philosophy and Co-Director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, says in the same CSHL Symposium interview that he disagrees with those opponents of Intelligent Design theory who, in his words, “want to say that [Darwin’s notion of] ‘evolution by natural selection’ explains apparent design, but not actual design.” In the view of Professor Dennett, the author of the acclaimed book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, “there is in fact real design in nature, and natural selection can explain it. You can have design without an intelligent designer.”

E.O. Wilson: A naturalist’s perspective on species in the genome age

The celebrated naturalist and prolific author E. O. Wilson provides in his CSHL Symposium interview a highly engaging look at the still unexplored reaches of the natural world. Currently University Research Professor Emeritus at Harvard, and Honorary Curator in Entomology of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Dr. Wilson is the recipient of more than 100 international medals and awards, including the National Medal of Science. Since 2003 he has been engaged in a Herculean effort to organize, launch and compile a comprehensive Encyclopedia of Life.

But as Wilson freely concedes in his Symposium interview, the scope of the task, even today, is not known. “The great scientist J.B.S Haldane, when told of how many beetle species there are, quipped that God must be fond of beetles. But there are small invertebrate groups, like the nematodes, and there are fungi, the number of species of which we still do not know,” Wilson says. “And we have absolutely no idea how many bacterial species there are! It could go into the tens and even hundreds of millions of species.”

Although an admirer of technologies such as genetic bar-coding to come from out of the genome revolution, Wilson stresses that it will always be necessary to do “the hard work in the field and in the museum and in the laboratory if we are to sort out what are probably tens of millions of species” of life on earth.

Twenty-two CSHL Symposium interviews are available.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455