Dr. Carol Greider proudly calls herself a “rogue scientist.” That iconoclastic approach led to her Nobel Prize-winning work on telomeres, and to becoming a champion for women in science.

“You can do whatever you want, but you have to like whatever you do.”

That’s what Carolyn “Carol” Greider’s father told her when she was growing up in Davis, California. He was a physicist at the University of California, and would often tout the freedoms that came with academia. But while Greider found her father’s work interesting and wished to follow in his footsteps as an academic researcher, she had a dilemma.

“It certainly felt like I wasn’t as good as the other kids,” she told The Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity in 2009. “I basically focused so much in my earlier education on just getting through and being able to do all the courses and get good grades that I wasn’t so much centered on, ‘What do I want to do in the future?’”

Born April 15, 1961, Greider grew up with dyslexia. She struggled with reading and spelling. Though her grades were good, her standardized test scores were poor.

When she began taking biology courses as an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, she discovered an academic environment that did not rely on test-taking: the laboratory. It was there that Greider excelled.

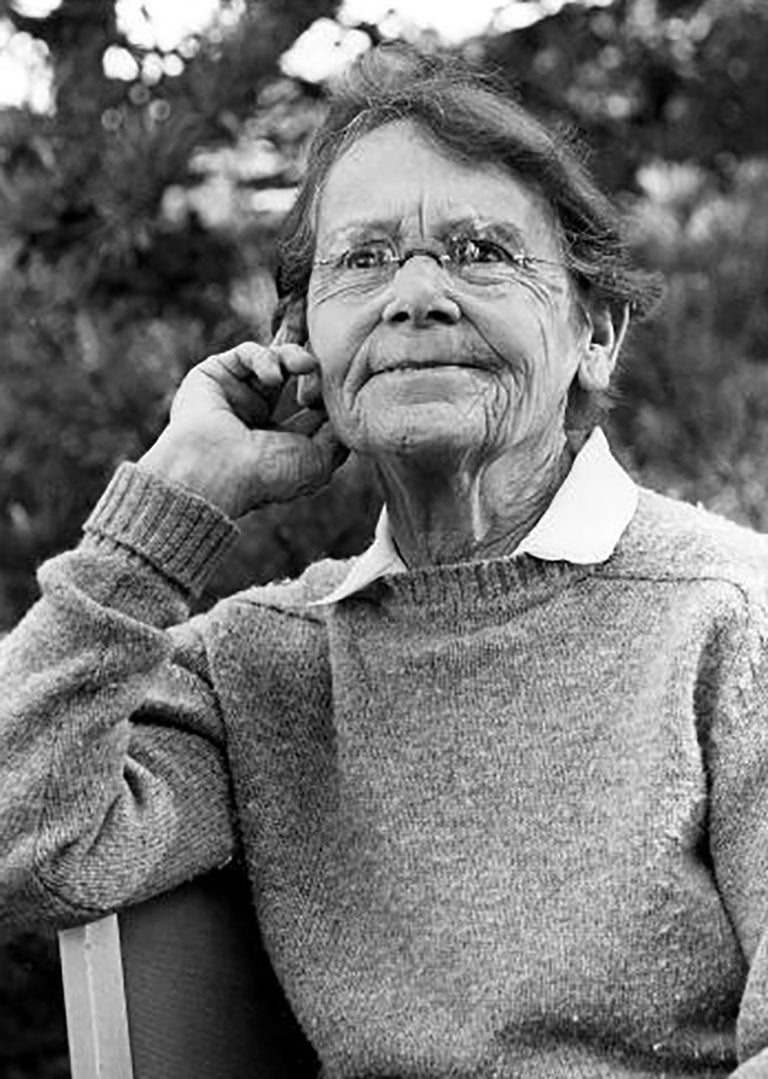

Later, as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, Greider focused on telomeres—genetic elements first discovered by one of her scientific heroes, the iconoclastic Barbara McClintock.

McClintock followed her weird hunch that genes can jump from place to place and disrupt other genes. When genes are disrupted, the loose ends of the chromosomes that hold them become unstable and can fuse together. But highly-stable chromosomes have protective end-caps that keep them from fraying, similar to the way the tips of shoelaces are kept together by plastic aglets. She called these sections “telomeres.”

U.C. Berkeley’s Elizabeth Blackburn and Harvard Medical School’s Jack Szostak later discovered that telomeres were simple repeated DNA sequences that shortened every time a cell divided. This was evidence that the telomeres were degrading in place of the important DNA they protected. However, it was unclear exactly how the telomeres got there in the first place.

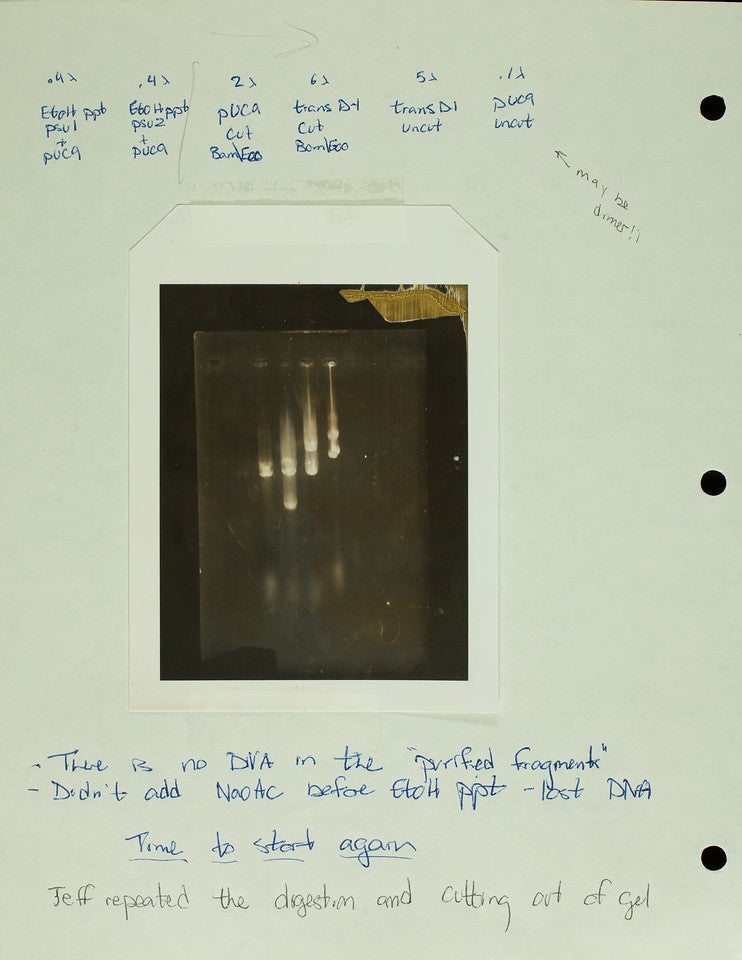

Greider solved this mystery quickly. On Christmas Day, 1984, Greider discovered the first signs of the enzyme telomerase, which contains a template for adding and restoring a cell’s telomere sequence. She continued to study telomerase as a Ph.D. student and eventually as a postdoctoral researcher in Blackburn’s lab.

Afterwards, Greider insisted that it was not any particular talent that led to her discovery but simply the right perspective, and lots of trial and error.

After completing her postdoctoral work with Blackburn in 1987, Greider was invited to be one of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s very first Fellows—an elite group of young researchers encouraged to pursue questions that few in their field are exploring. During her fellowship from 1988 to 1990, Greider discovered how telomerase adds protective telomere caps to the ends of chromosomes. And she found that cells that hijack that mechanism can bypass normal cellular aging, divide uncontrollably, and become cancer cells.

“We had no idea when we started this work that telomerase would be involved in cancer, but were simply curious about how chromosomes stayed intact,” Greider said after winning the Lasker Award in 2006. “Our approach shows that while you can do research that tries to answer specific questions about a disease, you can also just follow your nose.”

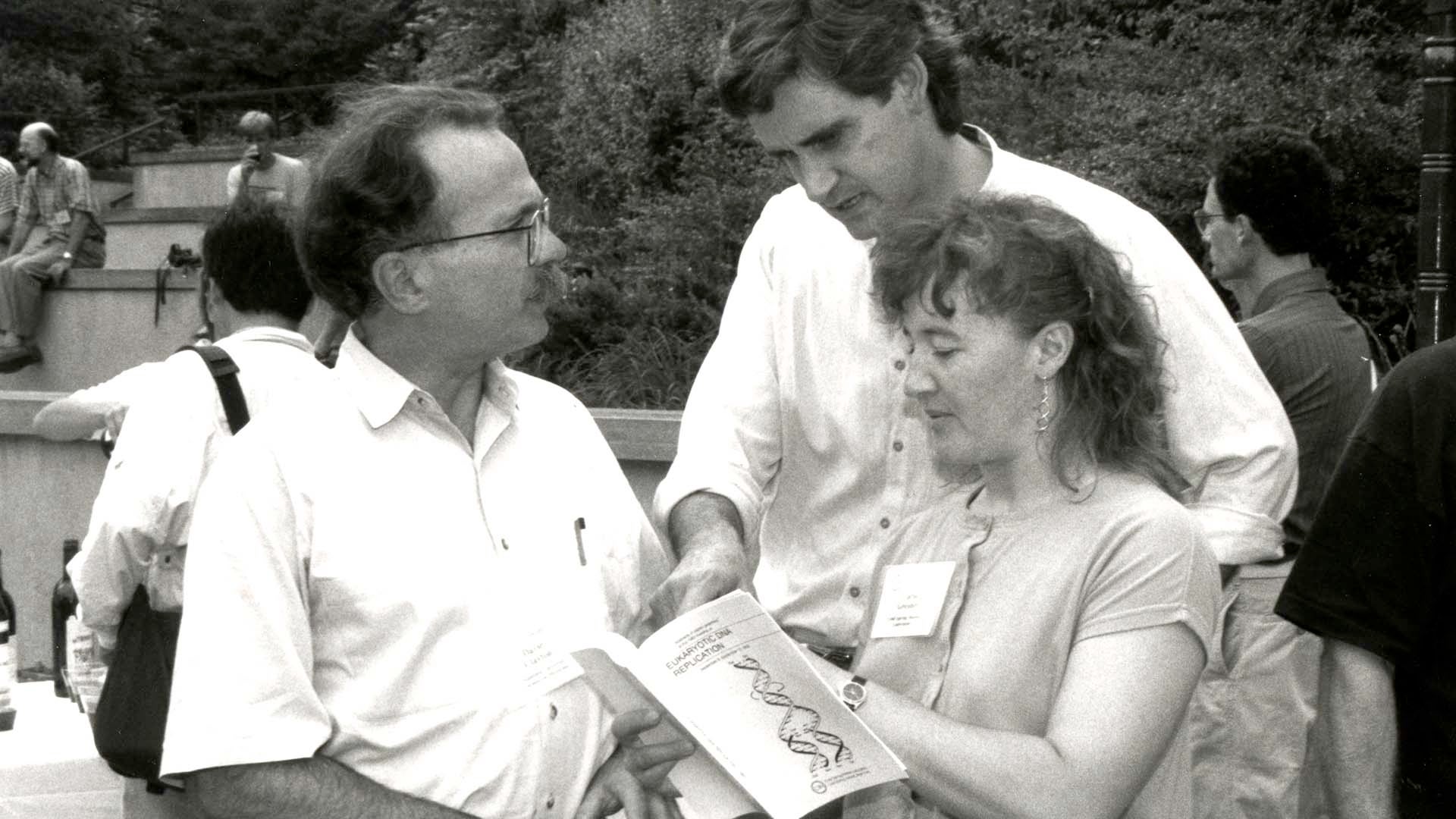

Greider was promoted to a full faculty position at CSHL in 1990. She spent the next seven years continuing and promoting telomere research. She co-organized the first major scientific meeting devoted to telomeres in 1994 and, alongside Blackburn, co-published the first detailed report on telomere research in 1995.

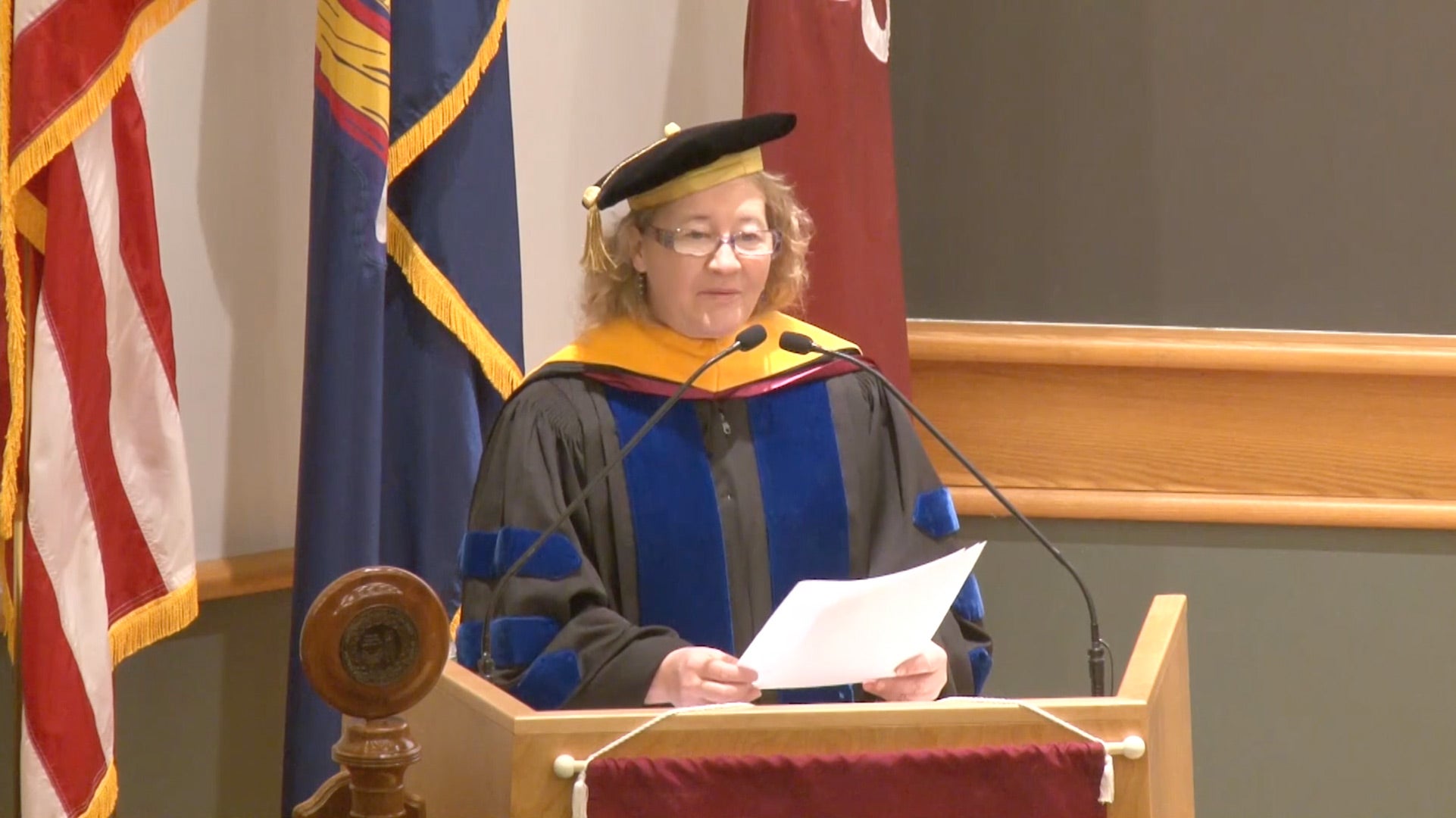

In 2009 the discoveries made by Greider and Blackburn were recognized around the world, when they shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Jack Szostak. The Nobel Prize committee declared that the trio had “added a new dimension to our understanding of the cell” and “shed new light on disease.”

“I follow the next most interesting thing because that’s what I like to do, rather than follow a particular grand plan,” Greider said.

In 1997, Greider moved her laboratory to the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. However, she remains a key member of CSHL’s Scientific Advisory Council and continues to organize many important meetings.

She has also been an advocate for CSHL’s efforts. In 2016, The New York Times dubbed Greider a “rogue biologist” for publishing her research on CSHL’s bioRxiv, the preprint server for the life sciences. The newspaper called it “a small act of information age defiance.” Since then bioRxiv has snowballed into a publishing juggernaut, with nearly 77,000 papers from 330,000 authors freely shared on the server since 2013.

All along, Greider promoted more equality for women in science. When she won the Nobel Prize in 2009, reporters commented that the telomere field had attracted an unusual number of women. Greider attributed this to “the founder effect,” where she and Blackburn had unwittingly become new sources of inspiration for young female scientists.

That’s why she’s been working hard to make research laboratories a welcoming workplace for all kinds of researchers. In 2018, she and CSHL Fellow Jason Sheltzer hosted a workshop at CSHL’s Banbury Center. They met with representatives from major scientific institutions and federal organizations to talk about ways to increase diversity in the STEM research workforce. Not long after, they published their conclusions and recommendations in a policy paper.

“If you always have people that have the same view testing out hypotheses, you’ll be stuck in your own bubble and won’t be able to advance the science,” Greider said.

She proves that everyone benefits when diverse perspectives address problems, whether those perspectives come from men, women, or someone struggling with dyslexia.

Written by: Brian Stallard, Content Developer/Communicator | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455