Opening the hormonal black box yields some surprises about sex

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have opened a black box in the brain whose contents explain one of the remarkable yet mysterious facts of life.

It’s been known for decades that an event occurring on the very first day of a male mouse’s life is required for masculine sexual and aggressive behaviors to emerge later on. Other mammals, primates included, have similarly important behavior—determining events related to the release of hormones during an early “critical period.” Until now, the identity of the cells that regulate “masculinization” in the mouse has been unclear.

After newborn male mice experience a surge of testosterone on their first day out of the womb, if all goes normally they will become typical males, marking territory with their urine, fighting with other males, and engaging in sexual activity, once their testes begin to generate testosterone some 4-6 weeks later—the mouse equivalent of human puberty. But they won’t manifest these male-typical behaviors if they don’t experience the initial testosterone surge.

The early mouse “masculinization” process has long been understood, counterintuitively, to be the work of estrogen acting in the mouse brain, not testosterone (which is converted to estrogen through the action of an enzyme called aromatase). In research appearing online today in Hormones and Behavior, CSHL Assistant Professor Jessica Tollkuhn and colleagues demonstrate for the first time the specific hormone receptors, brain cells and brain regions responsible for masculinization in the mouse. It’s part of Tollkuhn’s larger project aimed at more completely understanding how hormones define distinct neurodevelopmental trajectories in male and female brains.

Using genetic engineering to selectively delete the gene that encodes estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), Tollkuhn’s team established that masculinization depends exclusively upon ERα in inhibitory neurons (i.e., neurons activated by the neurotransmitter GABA). Surprisingly, deleting the ERα receptor in excitatory neurons, many of which are rich in ERα, had no impact on subsequent male behavior. “We knew that estrogen signaling early in life is important for masculinization,” Tollkuhn says, “but we didn’t know which parts of the brain involved in male behaviors really require estrogen receptors to properly masculinize an individual.”

The team’s experiments demonstrated that when ERα receptors are deleted in the male brain during embryonic development, males do not manifest typical behaviors at puberty. Such males were observed, atypically, to fight with females, not their male competitors. They also showed less zeal in marking their territory and in mating behavior. “It’s as if they became confused about who they were and how to act,” says Tollkuhn.

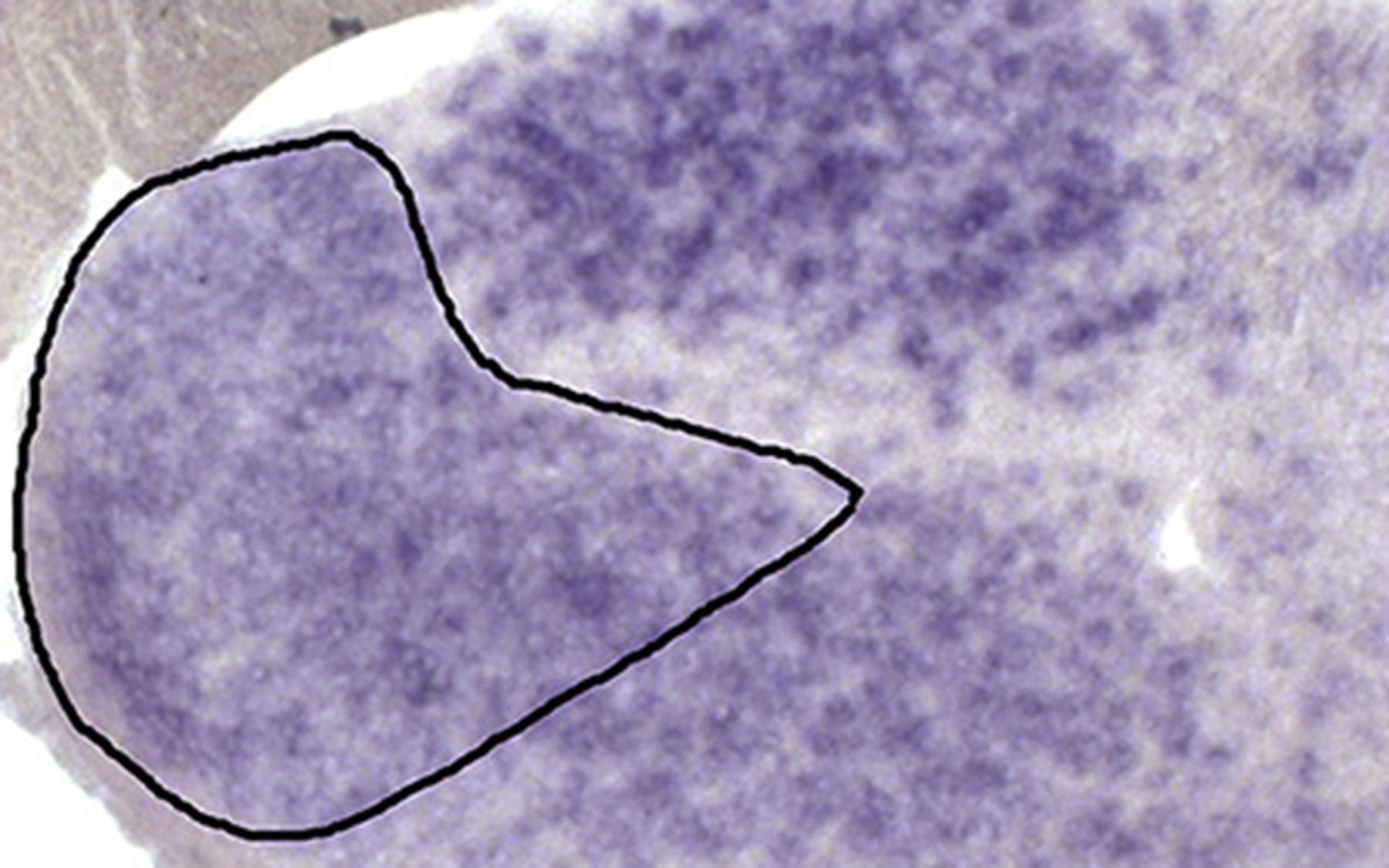

These “dysmasculinized” mutant males lacking ERα receptors also expressed genes encoding other hormone receptors at levels typical of females in two key brain regions: the MeA (medial amygdala) and the BNST (bed nucleus of the stria terminalis). These interconnected regions process pheromonal signals from other mice and broadcast information to downstream regions in the brain that ultimately dictate the display of social behaviors in the two sexes.

The team will next attempt to identify additional genes that differ between the sexes in the MeA and BNST. This, for Tollkuhn, is essential in order to understand how hormone signaling during early life has permanent effects on brain function, and what genes are involved in the onset, incidence, and symptoms of mental illnesses which affect the sexes differently, ranging from mood disorders to autism.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

The research described here was supported by a grant from Ted and Veda Stanley (Stanley Family Foundation) and CSHL Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508.

Citation

“Estrogen receptor alpha is required in GABAergic, but not glutamatergic, neurons to masculinize behavior” appears Friday, July 21, 2017 in Hormones & Behavior. The authors are: Melody V. Wu and Jessica Tollkuhn. The paper can be accessed at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/0018506X?sdc=1

Principal Investigator

Jessica Tollkuhn

Associate Professor

Cancer Center Member

Ph.D., University of California, San Diego, 2006