Small RNAs guide epigenetic modifications of DNA that lead to genome reprogramming

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — During embryonic development in humans and other mammals, sperm and egg cells are essentially wiped clean of chemical modifications to DNA called epigenetic marks. They are then held in reserve to await fertilization.

In flowering plants the scenario is dramatically different. Germ cells don’t even appear until the post-embryonic period—sometimes not until many years later. When they do appear, only some epigenetic marks are wiped away; some remain, carried over from prior generations—although until now little was known about how or to what extent.

“What we did know,” says Professor and HHMI-GBMF Investigator Rob Martienssen, Ph.D., of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), “was that epigenetic inheritance—the inheritance by offspring of chemical “tags” present in parental DNA that modify the expression of genes—is much more widespread in plants than in animals.”

In new research published online today in the journal Cell, Martienssen and colleagues show that genome reprogramming through these epigenetic mechanisms is guided by small RNAs and is passed on to the next generation.

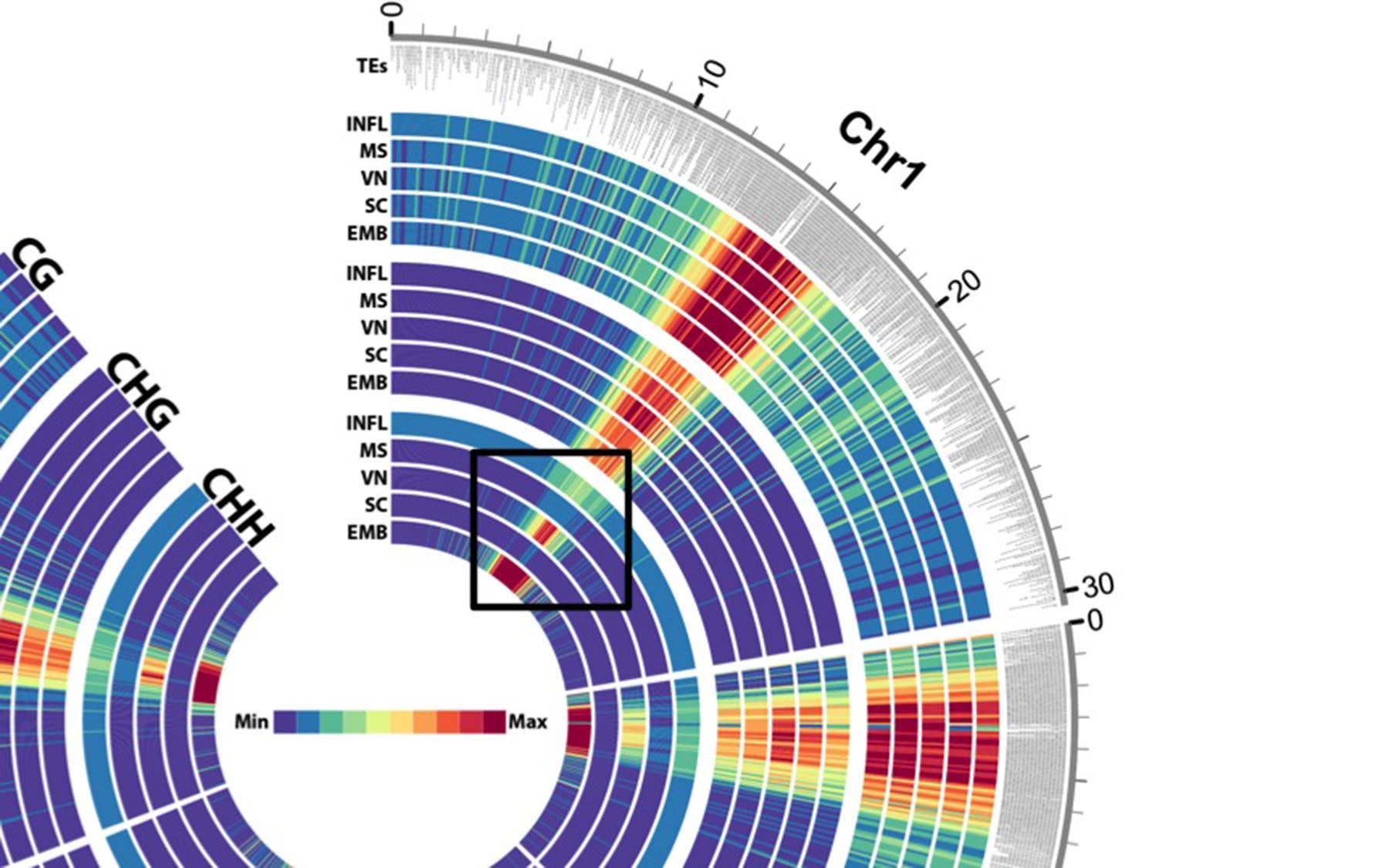

A circular “heat map” representation of a portion of the Arabidopsis plant genome focusing on chromosome 1 (Chr1). The color strength, from red (most) to blue/purple (least), represents the extent epigenetic modifications in different stages of plant germ cell development (INFL = inflorescence, MS = microspore, VN = vegetative nucleus, SC = sperm cell, EMB = embryo). The most epigenetically modified areas correspond to regions with the highest density of transposons (TEs). The black box outline highlights changes in a particular type of epigenetic modification during each stage of development.

Some DNA is tagged with epigenetic marks

It has long been known that in plants, as the male germline pollen grains develop, they give rise to two sperm cells, and a structure called the vegetative nucleus, which resembles “nurse cells” in animal germlines because it provides energy and nourishment to the sperm cells.

The DNA in germ cells can exist in two dramatically different states: in sperm cells, it is very densely packed and essentially inaccessible to the cellular machinery that enables individual genes to be “expressed.” In the vegetative cell, in which the packing is much looser, genes can be expressed.

DNA and chromosomal proteins can also be modified by various chemical groups (two common ones are methyl and acetyl) which tend to attach to the DNA and proteins at specific locations. These chemical tags are called epigenetic marks. The attachment of, for instance, a methyl group to a particular stretch of DNA containing a gene tends to prevent that gene from being accessed by the gene-expression machinery, and thus prevents the gene from being expressed.

Inherited methylation patterns are guided by small RNAs

Previous work by the Martienssen lab and their collaborators, including a team of pollen specialists from the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciencia in Lisbon, Portugal, has shown that these epigenetic mechanisms are important for keeping transposons in check. Also known as “jumping genes” for their ability to be expressed and then re-insert themselves at random into a different area of the genome, transposons are dangerous because they can cause damage to DNA and disrupt genetic function.

In the current study, probing further into the set of modifications on the DNA in plant pollen grains, Martienssen and colleagues decided to look at the particular set of chemical marks called methyl groups. When they separated out pollen grains in different stages of development they found distinct patterns of the attachment of methyl groups to DNA.

They also noticed the corresponding accumulation of small RNAs, including two classes of so-called short-interfering RNAs (siRNAs)—tiny RNA molecules, 21 or 24 nucleotides in length—involved in silencing gene expression. These small siRNAs act as guides to where methylation will occur, silencing gene expression.

Martienssen’s team discovered that while in sperm, some areas of DNA containing transposons had “lost” methyl groups, and thus had the potential to be expressed, the same stretches of DNA were observed to be methylated in the seed embryo. This was associated with the accumulation of 21-nucleotide-long siRNA in the mature pollen and 24-nucleotide-long siRNA in the seed embryo. Martienssen speculates that the loss of methylation in the sperm and subsequent re-methylation during fertilization may reflect an ancient mechanism for transposon recognition and silencing.

A second important observation made by the team was of the loss of methylation in “nurse cells.” Methylation at these same sites is retained in the associated sperm cells, and, too, is associated with accumulation of 24-nucleotide siRNA. This process results in areas of recurrent epigenetic marking that are pre-methylated in the germline sperm and carried on to the next generation.

“This is what, at least in part, enables plants to inherit acquired traits from prior generations—something that we mammals can rarely do,” Martienssen observes.

Being able to trace the inheritance of traits—both wanted and unwanted—in plants, and notably in agricultural crops, is important for farmers. Martienssen predicts that “defining inheritance through epigenetic modifications will influence the ways people think about cross-breeding to select for desired traits.” Such traits as resistance to temperature variation in crops have important agricultural and economic implications.

Written by: Edward Brydon, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

The research described in this release was supported by the following grants and funding agencies: NIH grant R01 GM067014 to R.A.M., grants PTDC/AGR-GPL/103778/2008 and PTDC/BIA-BCM/103787/2008 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) to J.D.B. and FCT grant PTDC/BIA-BCM/108044/2008 to J.A.F. F. Berger and P.E.J. were supported by Temasek Lifescience Laboratory. J.P.C. was supported by a graduate student fellowship from NSERC and by a grant from the Fred C. Gloeckner Foundation, F. Borges was supported by a FCT PhD fellowship SFRH/BD/48761/2008, and F.V.E. was funded by a Herbert Hoover postdoctoral fellowship from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Citation

“Reprogramming of DNA Methylation in Pollen Guides Epigenetic Inheritance via Small RNA” is published online in Cell on September 20, 2012. The authors are: Joseph P. Calarco, Filipe Borges, Mark T Donoghue, Frédéric Van Ex, Pauline E Jullien, Telma Lopes, Rui Gardner, Frédéric Berger, José A Feijó, Jörg D Becker, Robert A Martienssen. The paper can be obtained online at doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.001 via Cell press.

Principal Investigator

Rob Martienssen

Professor & HHMI Investigator

William J. Matheson Professor

Cancer Center Member

Ph.D., Cambridge University, 1986