Cold Spring Harbor, NY — About 10 years ago, several labs discovered that a gene called MELK is overexpressed, or turned on to a high degree, in many cancer cell types. This evidence has prompted multiple ongoing clinical trials to test whether drugs that inhibit MELK can treat cancer in patients. Now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) researchers, led by CSHL Fellow Jason Sheltzer, report that MELK is not actually involved in cancer.

Furthermore, Sheltzer and his colleagues suggest that the discrepancy with previous findings results from inherent flaws in the scientific techniques that have been used to link MELK to cancer.

“Our study is a good illustration of the self-correcting nature of science,” Sheltzer says.

Over the past few years, Sheltzer and Stony Brook University students Chris Giuliano and Ann Lin have been performing genomic analyses on tumors surgically removed from cancer patients. Their goal has been to identify genes whose activity levels are correlated with low patient survival rates. The researchers then planned to use a gene-editing technology called CRISPR to eliminate the genes from different cancer cell lines one at a time to see if they could kill the cells.

This is where MELK comes in. “Like other labs, we found that MELK tended to be very highly expressed in patients who did not survive very long,” Sheltzer says.

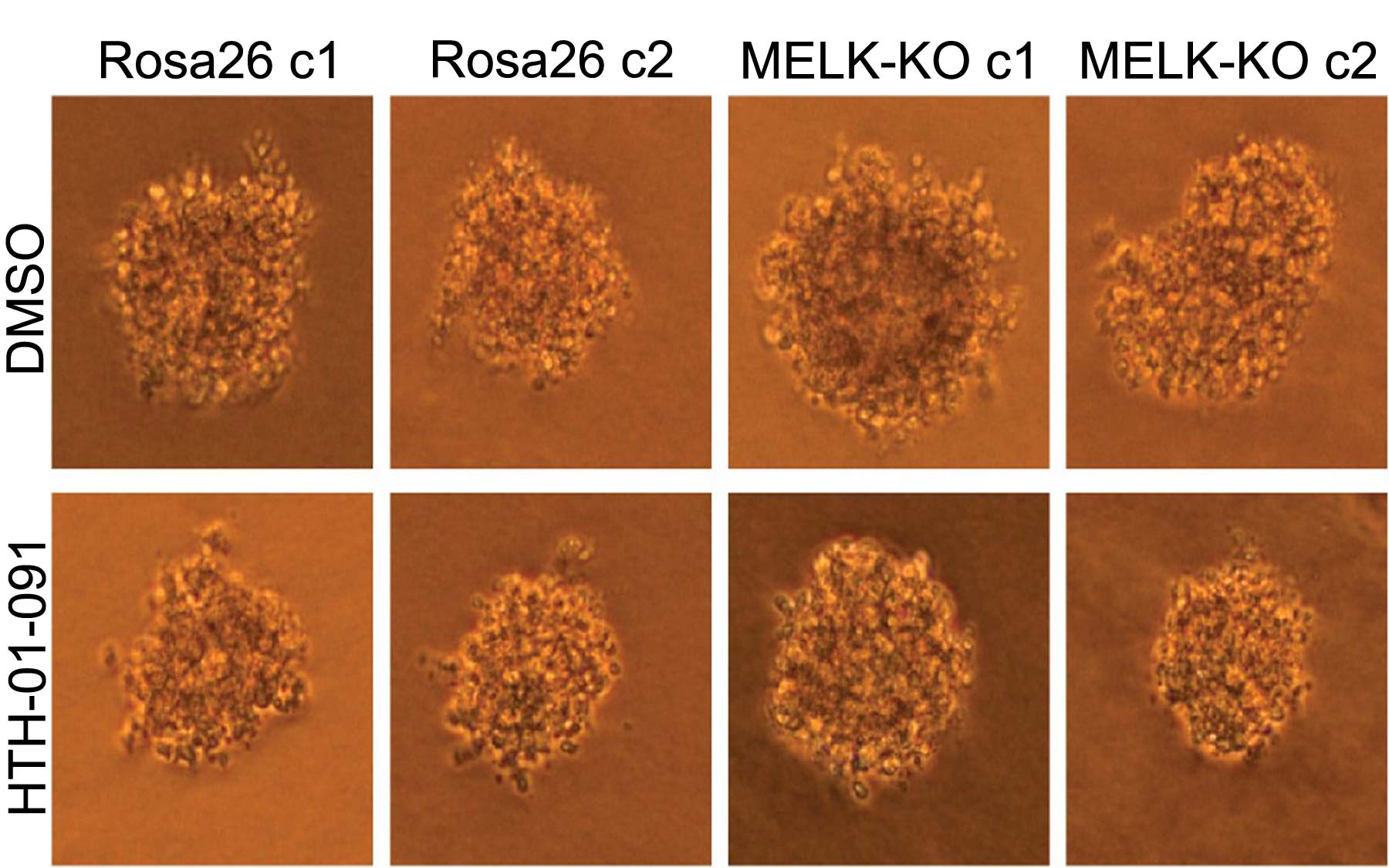

Because so many previous studies using a variety of other methods had shown that MELK was essential for cancer cells, Sheltzer believed that his team could use the gene as a positive control in their CRISPR experiments. “We thought we would eliminate MELK and show that it killed cancer cells. Then we could know that our CRISPR techniques were working,” Sheltzer says. “But, to our great surprise, the cancer cells didn’t die. They just didn’t care.”

The researchers then performed several experiments to ensure the CRISPR technique was working. “We eventually had to conclude that our technique was fine,” Sheltzer says. “Rather, it was the previous findings about MELK’s role in cancer that were incorrect.”

Sheltzer thinks some of the techniques have been prone to error due to what scientists call “off-target effects.” One such technique, called RNA interference, harnesses a cellular mechanism controlling gene expression to switch off specific genes. “You think you’re knocking down one gene, but in reality, those techniques are not very specific, so you’re also hitting a number of other different genes,” Sheltzer says.

“We think this might be a common problem,” Sheltzer adds. “There may be other genes like MELK out there, and we want to use CRISPR to identify the best possible targets for drug development.”

Written by: Chris Palmer, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

National Institutes of Health

Citation

Giuliano, CJ et al, “MELK expression correlates with tumor mitotic activity but is not required for cancer growth,” appeared online in eLIFE February 8, 2018.