Study implicates two human genes in the third-leading cause of cancer deaths

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — By generating tumors in laboratory mice that mimic human liver cancer and by comparing the DNA of mouse and human tumors, researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have identified two genes that are likely to play a role in the third leading cause of human cancer deaths. The study also establishes an efficient and adaptable method for exploring the biology of liver cancer, for validating potential therapeutic targets, and for testing new treatments. The findings are reported in today’s issue of the journal Cell.

“There has been a long search for animal models that could be predictive of the genes involved in human cancers. These researchers have taken a large step forward in this search and are on a clear path to proving that well-designed animal models can precisely reflect the events observed in human cancers,” said Arnold J. Levine of The Institute for Advanced Studies, who was not involved in the study.

Liver cancer (“hepatocellular carcinoma” or HCC) is the fifth most frequent neoplasm worldwide. However, owing to the lack of effective treatment options, it is the third leading cause of cancer deaths.

To gain a better understanding of the molecular causes of HCC, the researchers—led by Scott Lowe of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory—devised a strategy for genetically engineering liver stem cells, harvested from mouse embryos, and subsequently transplanting the cells into adult mice. Following transplantation (by injection into the spleen), the cells can become part of the recipient mouse’s liver.

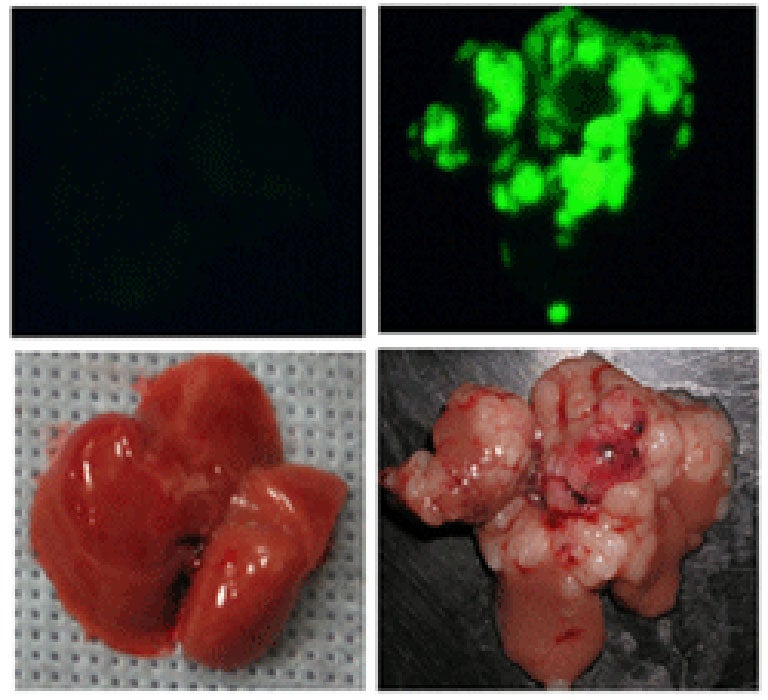

Depending on the initial, genetically engineered makeup of the liver stem cells, and on genetic alterations that occur spontaneously after they are transplanted, the cells can have a high probability of forming tumors (see image). Scanning the DNA of such tumors has the potential to uncover the relevant spontaneous genetic alterations and reveal the corresponding genes that, when altered, contribute to liver cancer.

In one set of experiments, the scientists engineered the liver stem cells in three ways, two of which were designed to mimic the genetic lesions that are known to occur in human liver and other cancers (namely, deletion of the p53 gene and activation of the Myc gene). A third genetic modification (the insertion of a gene that encodes a fluorescent marker protein) enabled the researchers to visualize the transplanted cells, and their descendants, in the adult mice.

Transplanted cells lacking the p53 gene and bearing an activated version of the Myc gene rapidly gave rise to aggressive, invasive liver tumors. Scanning the DNA of these tumors revealed that a specific segment of mouse chromosome 9 was amplified—or present in excess copies—compared to the DNA of healthy mouse liver cells.

Because this segment of mouse DNA carried several genes, the researchers turned to the human genome to help them narrow down which gene (or genes, as it turned out) was the culprit in liver cancer.

In parallel with their analysis of the mouse liver tumors, the researchers scanned the DNA of human liver and other tumors. Remarkably, they found that a region of human chromosome 11 that is evolutionarily related to the segment of mouse chromosome 9 was amplified in several of the human tumors.

Additional experiments revealed that two genes—Yap and cIAP1—were both consistently over-expressed in both the mouse and human tumors. Thus, when produced at abnormally high levels, proteins encoded by the Yap and cIAP1 genes are likely to contribute significantly to human liver and other cancers.

The study also revealed that whereas producing either the Yap or the cIAP1 protein at an abnormally high level triggers tumor formation in mice, simultaneously overproducing both proteins dramatically accelerates tumor formation. Therefore, these proteins and others in the biochemical pathways they control are attractive candidates for the development of novel cancer therapies.

The lead author of the study, which involved researchers from five institutions in Europe, Asia, Australia, and the U.S., is Lars Zender who is the Andrew Seligson Clinical Fellow at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Written by: Communications Department | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455