Cancer researcher Mikala Egeblad aims to make cancer-fighting drugs more effective by preventing healthy cells from helping the enemy survive.

The battlegrounds of the war on cancer—the landscape of healthy cells and molecules that make up the tumor’s “microenvironment”—sometimes fade to the background in cancer research. But CSHL Associate Professor Mikala Egeblad and her team have been making movies that show there’s quite a bit of action happening between cancer cells and healthy cells.“I think it’s important to know that the microenvironment can determine how cancer cells respond to therapy, and it is interspersed within the tumor cells,” Egeblad says, explaining that, “it’s not just sort the border region around the tumor. You find these non-cancerous host cells in between the cancer cells.”

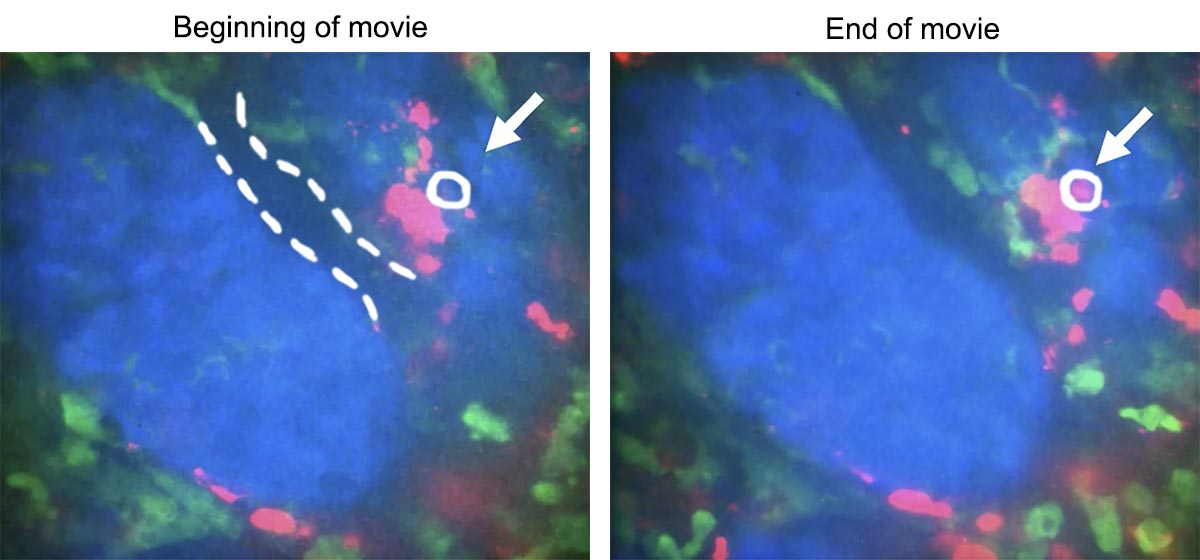

The glowing, wriggling blobs in the movie above are a mixture of healthy and cancerous cells. It happens quickly, but what you’re watching suggests that cancer cells may trick a patient’s healthy cells into helping the cancer cells survive.

You can see this clearly in the video, which shows an area of a mouse breast tumor that’s pretty densely packed with cancer cells stained with a blue dye. Even in this cancer-crowded area, there are healthy immune cells, dyed green, moving amongst the cancer cells.

These green immune cells are mostly macrophages and monocytes, which mature into macrophages, according to Egeblad. Macrophages are best known for killing bacteria in the body by swallowing and destroying them, but they also help out with tasks such as healing wounds by stimulating cell growth with chemical signals.

In the picture below, that dark streak running through the frame is a blood vessel, partially traced with dotted white lines in the left panel. A day earlier, a chemotherapeutic drug called doxorubicin was coursing through that vessel and leaked out onto some of the cells nearby.

One of those leaked-onto cells is a cancer cell within the white circles (the dye tends to blur the boundaries between cells). The cancer cell turns from blue to red, indicating that it is dying. The red dye within the tumor can’t penetrate the cell membranes of healthy cells. But as a cell dies, the membrane becomes permeable and the red dye flows into the cell.

“These are cells that are recognizing that there’s cell death going on so they’re coming in response to that,” Egeblad says. “What we did find is that they ultimately drive resistance to the chemotherapy.”

These immune cells carry around a lot of different proteins, Egeblad explains. Some of these proteins have the power to signal whether or not a cell will die. The net balance of ‘die’ or ‘survive’ signals from a cell’s surroundings typically determines its fate.

“If a cancer cell is getting ‘survive’ signals from these green cells or from other cells in the environment, then it won’t die even though it gets the same amount of ‘die’ signals,” Egeblad says.

Looking closely at how the cancer cells interact with their environment suggested that these healthy cells provide cancer cells with proteins that signal ‘survive.’ In other words, those green immune cells seem to be helping the cancer cells resist the chemotherapy drug. Egeblad hopes that this insight might lead to a way to modify these cancer-aiding immune cells so that the drug can have a greater effect.

“If survival signals are the most important mechanism, then you could envision just taking those signals away at any one time after chemotherapy resistance develops. Then the drugs that didn’t work could work again,” she reasons. “It’s sort of a way to sensitize tumors to the drugs that we already have, getting those drugs to work better.”

Mikala Egeblad explains her research on tumor microenvironments

This video is from a paper that Egeblad and her colleagues published back in 2012, but the work continues. In particular, they’re focusing on finding ways to beneficially modify the microenvironment in late-stage cancers, which are especially tough to treat because they’ve spread to other parts of the body.

Just this week, Egeblad got a new microscope that will allow the team to obtain better images of tumors in the lungs, a place to which breast cancer commonly spreads—so stay tuned for more videos, and more discoveries.