Sometimes viruses cause harmful infections, but students in the DNA Learning Center’s Urban Barcode Research Program identified a new virus that could help fight dangerous infections.

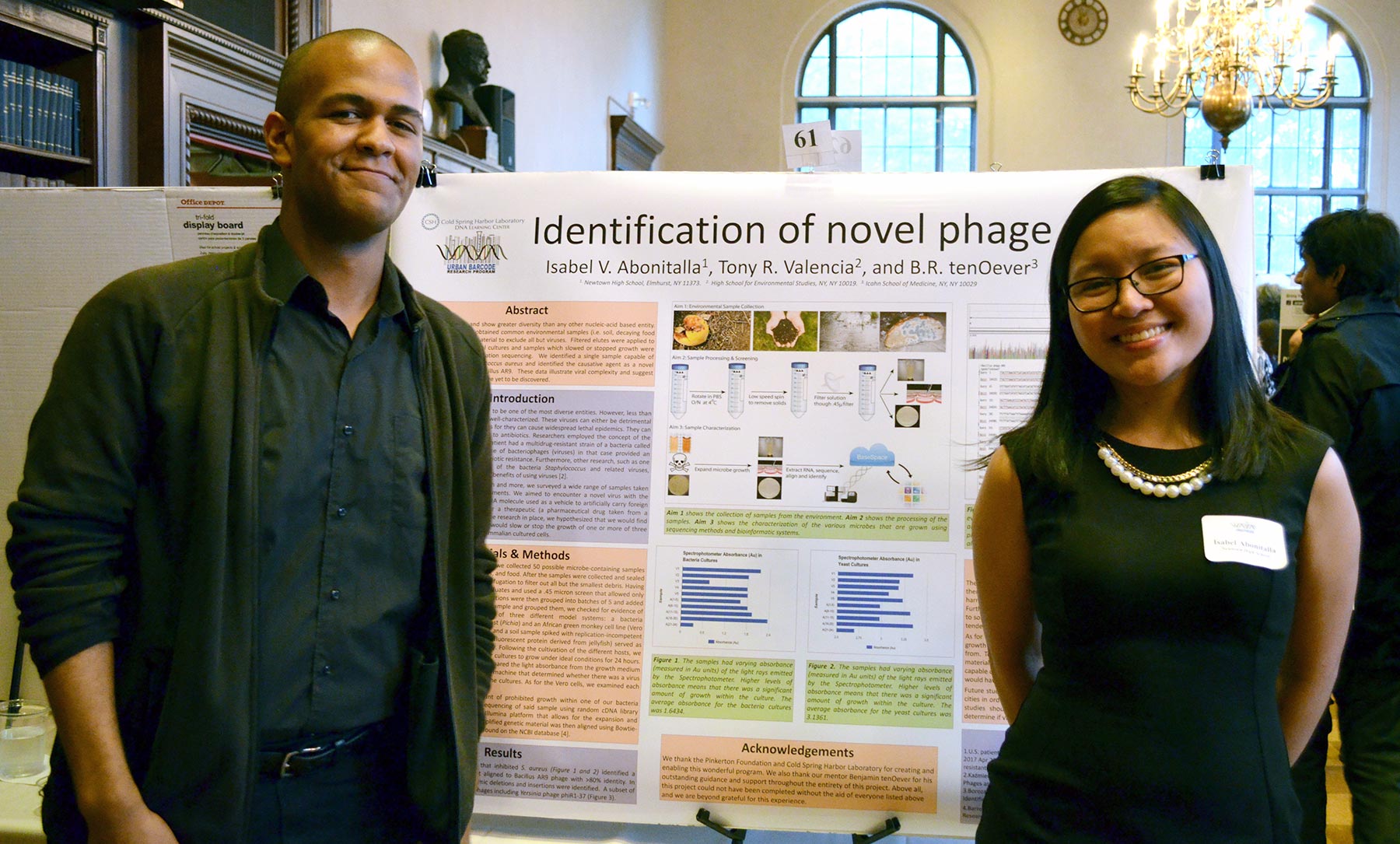

Viruses have a pretty bad reputation, but high schoolers Tony Valencia and Isabel Abonitalla are now determined to spread the idea that viruses can be our friends. They learned about the counterintuitive concept of using viruses to treat bacterial infection from their scientific mentor in the DNA Learning Center’s Urban Barcode Research Program. Now, they see viruses as an indispensable tool in mitigating the looming crisis of antibiotic resistance—the inability of current medicines to treat certain infections.Like all students in the program, who presented their projects at a symposium in May, Valenica and Abonitalla used a technique known as DNA barcoding. This approach employs short, unique patterns or “barcodes” in DNA to identify living things. It’s a method similar to the barcode system that stores use to identify products.

Unlike the viruses that give us the flu and other infections, certain viruses known as bacteriophages, or simply phages, prey on bacteria. Phage therapy is a century-old idea that harnesses the bacteria-killing power of these viruses to clear up infections in humans.

Mentor Benjamin tenOever of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, with whom the program paired the students, helped Abonitalla and Valencia identify a new phage in which they see therapeutic potential for their research project. But perhaps just as importantly, “Benjamin taught me that scientists are everyday people who do great things,” says Valencia.

Phage therapy hasn’t caught on outside of Russia and a handful of other countries in part because giving viruses to patients is, understandably, an alarming idea for many people. But Valencia explains, “once we apply viruses to infections, they will only attack those infectious cells, because [phage] viruses are unique to one type of bacteria.”

Find out how phages helped scientists determine that DNA is the genetic material.

Abonitalla and Valencia weren’t looking for phage therapy candidates when they started the project. tenOever initially suggested that they study the biodiversity of viruses in New York City, but the students’ interests quickly took the project in a new direction. Abonitalla remembers that “Tony and I stayed past the appointment because we had so many questions that weren’t necessarily related to the topic, but we were still allowed to explore those.”

After a couple of discussions, they decided to search for a phage that affects yeast, because it may be possible to adapt such a virus for use as a therapeutic. They ended up testing the new phage that they identified through DNA barcoding on the bacteria known as “staph” and on monkey cells as well, since candidates for therapeutics must not harm the cells of humans, who are also in the primate family. They found that the phage slowed the growth of only the staph bacteria, which is known for causing resistant infections in people. Many more tests will be needed, however, to determine whether it can be developed into a targeted therapy.

It’s difficult to overstate how excited Abonitalla and Valencia are about their work. They agree that “changing the face of medicine” is now “what we want to do.” For Abonitalla, right now that means pursuing research, while Valencia is passionate about public health. He used to be focused on the political rather than scientific issues, in part because he admits that, “I don’t want to go into a field where everyone is boring.” But tenOever showed him that, “scientists can be really cool,” and that makes a big difference.