Through this Facebook post, Hwang learned that Jae-Seok Roe was already working at CSHL, right across the hall from the lab for which Hwang interviewed. The two had met in 2002 while they were students in South Korea, and Roe, the younger of the pair, was shadowing Hwang in a lab at Seoul National University. You could say that they worked together, but Roe counters, “we just played!”

They hit it off, but drifted in different directions. Roe became infatuated with the burgeoning field of epigenetics, the study of how cells can have different properties despite possessing precisely the same genetic material. It’s how the same DNA can create either a brain cell or a skin cell—epigenetic changes can switch certain genes on and off in different cells without changing the sequence. Hwang, on the other hand, became a master of modeling cancer in the lab. As a result, “we didn’t expect that we were going to work together,” says Roe, even once reunited at CSHL. But these differences are exactly what made them a powerful team.

What brought them together was pancreatic cancer, which kills over 90 percent of its victims within just five years largely because of its propensity to spread. Once a pancreas tumor forms, cancer cells often break away and take up residence in a new body part, a process called metastasis. Hwang explains that, “for a long time, people tried to identify the genetic alterations responsible for metastasis, but it was not that successful.”

Scientists had identified many of the genetic changes that occur when healthy cells turn into pancreatic cancer cells, but had found only those same DNA sequence changes in the roving cancer cells, the real killers. They wanted to know how these cells become so dangerous, because that could reveal a way to stop them. Many scientists speculated that epigenetic changes, which wouldn’t show up in the cells’ DNA sequence, drive pancreatic cancer metastasis. The challenge was proving it.

The problem captivated both Roe, because of his interest in epigenetics, and Hwang, because of his determination to better understand pancreatic cancer through animal models of the illness. They engaged in lively discussions on the subject over wine and cheese on CSHL’s campus and at joint family barbecues at home, each contributing ideas from their own area of expertise. Eventually, the thought dawned on them, “Well, what if we just work together?”

Find out how CSHL’s culture of informality and equality makes it “A Lab Like No Other.”

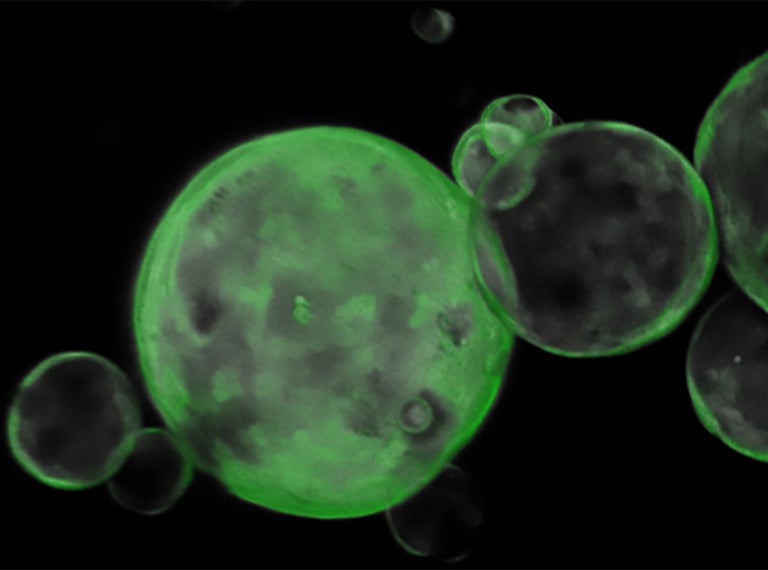

From that moment on, the project came together remarkably quickly. Hwang is an expert on pancreatic cancer organoids, a 3D modeling system that allows scientists to grow tumors in a dish from cancer cells sampled from humans or lab mice. This was exactly the platform that an epigeneticist like Roe needed to solve the mystery of pancreatic cancer metastasis. “I had the fast track to use the greatest source with no time limit, with no hesitation,” Roe says.

The “no hesitation” part is important. Instead of the five or so years that a project like this might normally take, they finished in just two and a half. Since Hwang and Roe were close friends, they were able to talk freely and frequently with one another. “It’s not like we needed to make an appointment to have a discussion,” Roe points out. “Before being a scientist, he was my brother.”

When they joined forces to probe pancreatic cancer cells for the secret to metastasis, Hwang says they found “dramatic epigenetic changes” emerged in cells that broke away from the primary tumor to colonize other parts of the body. These epigenetic changes seem to allow the cancer cells to “remember” what it was like to be an embryo, when the pancreas was first forming. The qualities that cells have at that stage could make it easier for them to break away from the pancreas to form colonies elsewhere.

This discovery is a major step in understanding the deadly process of pancreatic cancer metastasis, and Hwang and Roe are eager to reveal the rest of the story. “We just opened the door,” Roe says.