“My God, she picked me,” he said to the first investigator who entered the room.

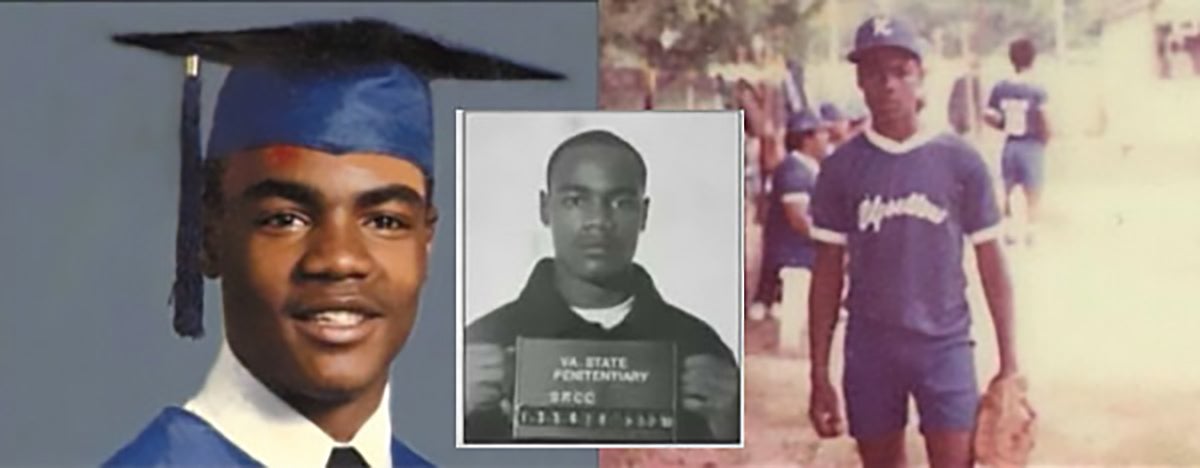

Tears streamed down Anderson’s face and onto the Hanover County station floor. At only 18, he was labeled a rapist and sentenced to 210 years in prison. The year was 1982.

Six long years later, John Otis Lincoln showed up in a Virginia court to confess that he was the one who raped the petite blond woman who had mistakenly identified Anderson as her attacker. Some said that Lincoln’s conscience must have finally caught up to him.

That should have meant that Anderson would soon reclaim his freedom. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened.

Instead, Lincoln’s testimony was found to be lacking, and he once again escaped justice.

“I really thought I’d experience freedom in another lifetime. I thought I would spend the rest of my life in prison,” Anderson admitted 15 years later.

By then, he was no prisoner. The man wore a sharp tux and matching bowtie with pride, smile lines creasing across a face that had once been slick with bitter tears.

He was a guest speaker at a function celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the discovery of the double helix, and had come to convey his own appreciation of the work done in DNA research.

A year earlier, Anderson had become the 99th US citizen to be exonerated with genetic evidence.

According to Peter Neufeld, one of Anderson’s lawyers, stories like this are not unusual.

“About 330 people have so far been exonerated due to DNA testing, and we think that this is just the tip of the iceberg,” Neufeld recently explained during a public lecture at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Neufeld is the co-founder of an organization called the Innocence Project, which helped usher dependable DNA testing into criminal trials and case reviews. The aim, according to Neufeld, is to correct injustices and improve policing procedures through science.

Both Neufeld and co-founder Barry Scheck often relate how CSHL played a role in the Project’s humble beginning. Long before “forensic DNA testing” meant a second chance, CSHL’s Dr. Jan Witkowski decided to hold a Banbury Conference that would touch upon the viability of that very concept. It was here where Scheck, Neufeld, and host of other experts began to truly consider how to go about moving fresh research techniques into crime-labs and courtrooms.

Now nearly 30 years later, Neufeld returned to the Laboratory to tell the public about the new challenges that the Innocence Project faces.

Neufeld described the case of Donald Eugene Gates in particular—a man who spent a whopping 27 years in prison after being convicted of a brutal rape and murder the same year Anderson’s dreams were cut short.

In Gate’s case, key testimony came from an informant named Gerald Mack Smith.

Learn about Gerald Mack Smith

Smith, being a criminal himself, could not be trusted, but local police concluded that between questionable testimony and questionable hair evidence found on the victim, they had a strong case.

And this, Neufeld argues, is the dangerous flaw in police procedure that has led to at least 330 innocent people to being wrongfully accused and convicted.

Neufeld on evidence

Neufeld on confessions

According to the Innocence Project founder, police procedure still often lacks the thorough and objective approach it needs to properly assess evidence—an approach, he argues, that is already an essential part of the basic scientific method.

Anderson’s own tragic case illustrates this point all too vividly. His color photo was presented to the victim among a series of black and white prints. Then, in that fateful lineup, he was the only man standing whose photo the victim had recently seen.

This, experts now suggest, was what led the victim to overlook Lincoln, who was also in the lineup

The result was Anderson becoming “the only case in America where the real perpetrator was shown to the victim, and instead she picked an innocent guy,” Neufeld added.

Now, the hope is that with police stations and courtrooms learning to respect the scientific method, Anderson’s will stay the only case.

Interested in attending future lectures at CSHL? Check out all our events!