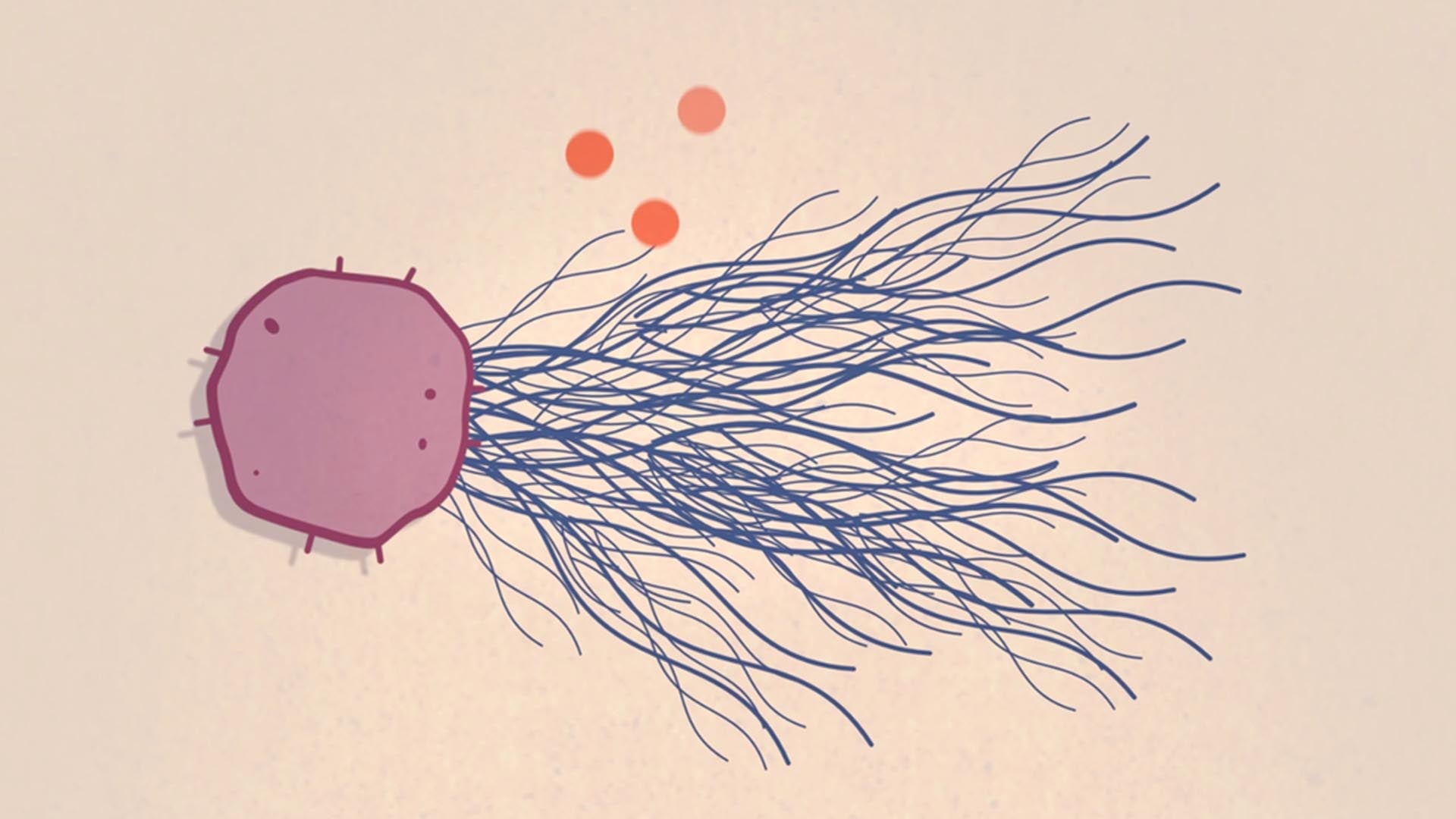

Cold Spring Harbor Lab Associate Professor Mikala Egeblad studied cancer before the COVID-19 pandemic. But when she read reports about severe cases of the disease, she realized that those coronavirus patients might suffer from something similar to what some cancer patients experience. Neutrophils, a common type of white blood cells, try to trap and digest cancer cells and pathogens in spaces between cells. In a suicide manuever, they spray their prey with sticky strands of their own DNA, and use toxins stuck to the DNA to break apart the enemy. An overabundance of the strange, stringy structures—neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)—may be responsible for turning some cases of COVID-19 more deadly.

So Egeblad worked with a “NETwork” of researchers to repurpose and share their research on NETs to COVID-19.

NETs aren’t always harmful for people. The neutrophils that create them are the most common type of white blood cell and a natural enemy of invading pathogens, such as viruses. However, health professionals know that when NETs prove ineffective against an infection or even cancer, they can build up in the body and become harmful.

When toxic NETs accumulate in the lungs, it results in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Patients with ARDS have difficulty breathing and often require assisted ventilation. In this way, a persistent virus can cause NETs to unintentionally harm the very organ they’re designed to protect. The NETwork of researchers is now engaged in research and clinical trials to target the NETs, including using a drug to chew up the DNA strands.

Written by: Brian Stallard, Content Developer/Communicator | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455